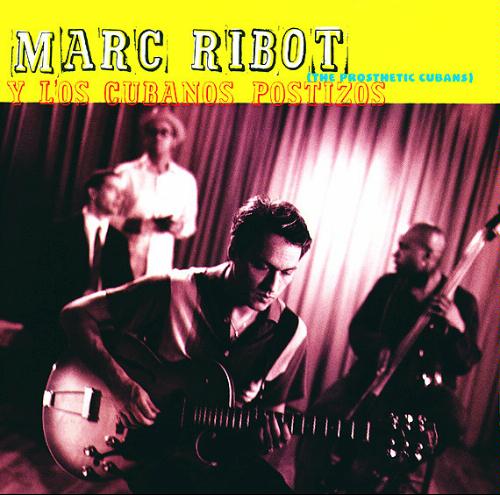

BY ZIVIT SHLANK JAZZ CORRESPONDENT Wizardly guitarist/composer Marc Ribot defies classification. By his own admission, he’s spent his entire career trying to fit into one box or another but always failed miserably. He’s played with the likes of Chuck Berry, Tom Waits, Elvis Costello, Medeski Martin & Wood, The Black Keys and Philadelphia’s own McCoy Tyner, among countless others. Ribot’s own recorded works have explored the nether regions of Afro-Cuban jazz, noir blues, abstract rock, sweet soul, prickly post-punk, and exotic world styles — to which he brings his incandescent improvisatory six-string magic. You may have heard his otherworldly guitar work amidst the scores to such films as Where The Wild Things Are, Walk The Line and The Departed. His own projects include the faux-Havana heavenliness of Los Cubanos Postizos, his Albert Ayler salute Spiritual Unity and more recently, the raucously beguiling, post-everything-ness of Ceramic Dog, which he brings to Johnny Brendas tonight courtesy of the hep folks at Ars Nova Workshop. Phawker recently chatted with Marc just days before embarking to Europe to kick off his latest tour.

BY ZIVIT SHLANK JAZZ CORRESPONDENT Wizardly guitarist/composer Marc Ribot defies classification. By his own admission, he’s spent his entire career trying to fit into one box or another but always failed miserably. He’s played with the likes of Chuck Berry, Tom Waits, Elvis Costello, Medeski Martin & Wood, The Black Keys and Philadelphia’s own McCoy Tyner, among countless others. Ribot’s own recorded works have explored the nether regions of Afro-Cuban jazz, noir blues, abstract rock, sweet soul, prickly post-punk, and exotic world styles — to which he brings his incandescent improvisatory six-string magic. You may have heard his otherworldly guitar work amidst the scores to such films as Where The Wild Things Are, Walk The Line and The Departed. His own projects include the faux-Havana heavenliness of Los Cubanos Postizos, his Albert Ayler salute Spiritual Unity and more recently, the raucously beguiling, post-everything-ness of Ceramic Dog, which he brings to Johnny Brendas tonight courtesy of the hep folks at Ars Nova Workshop. Phawker recently chatted with Marc just days before embarking to Europe to kick off his latest tour.

PHAWKER: Can you recall that first artist, song or experience that inspired you to make music?

MARC RIBOT: Before I played guitar, I played trumpet. I didn’t play trumpet because of any epiphany about a love of music, I did it because I was an idiot and I was a boy. All the girls chose violin and all the boys chose trumpet. And there were probably some Freudian reasons behind this, I imagine. But I do remember when we had band practice I would get very excited, very carried away. I was in another world. What led me to switch from trumpet to guitar were braces. Initially it was the music of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones that my cousin listened to. It was mostly rock music, hearing it on the radio and at school dances and I loved it. The first live music I ever witnessed was from a friend of the family, a Haitian classical guitarist/composer who would become my teacher, Frantz Casseus. I remembered he’d come around to family events and I guess he got bored cause he used to sit around and play. I would sit around and listen just amazed. I eventually realized that the sound coming out of those Beatles and Stones records had something to do with guitar. Coupled with my braces hurting away as I tried to play trumpet, I decided to take a stab at guitar. It seemed obvious that since he was a friend that Frantz should teach me.

and I was a boy. All the girls chose violin and all the boys chose trumpet. And there were probably some Freudian reasons behind this, I imagine. But I do remember when we had band practice I would get very excited, very carried away. I was in another world. What led me to switch from trumpet to guitar were braces. Initially it was the music of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones that my cousin listened to. It was mostly rock music, hearing it on the radio and at school dances and I loved it. The first live music I ever witnessed was from a friend of the family, a Haitian classical guitarist/composer who would become my teacher, Frantz Casseus. I remembered he’d come around to family events and I guess he got bored cause he used to sit around and play. I would sit around and listen just amazed. I eventually realized that the sound coming out of those Beatles and Stones records had something to do with guitar. Coupled with my braces hurting away as I tried to play trumpet, I decided to take a stab at guitar. It seemed obvious that since he was a friend that Frantz should teach me.

PHAWKER: That’s interesting considering your desire to play guitar stemmed from your love of rock.

MAR RIBOT: I didn’t have a clue that the music he made was different than what Keith Richards played. I was completely ignorant and thought “Well, he plays guitar, I wanna learn guitar so I should study with Frantz.” He started me on classical music, even though I had no idea what it was. During this time, I remember getting very excited when I heard the song “Masters of War” by Bob Dylan. For a lot of people it was the political sentiments of the song that got them riled up, but for me I was knocked out because you could play an add9 chord just by picking up your index finger and that was so cool. Somewhere in there I also thought that if I played guitar, girls would like me. Turned out to be wrong by the way. But I thought it at the time and that inspired me to practice. In my early relation with all this stuff, again it wasn’t so much an experience with a particular piece of music, but what I noticed with myself and other guitarists, at some point a serious social dysfunction occurs. In its early stages, guitar is not a very social instrument. Most of us learn it playing alone for years and years before we try it in a group. It doesn’t seem very natural or healthy for a young person to spend hours a day, sitting alone in a room working on this instead of going out with their friends breaking windows or whatever. I took lessons with Frantz, but the year I started to feel like a guitarist was when I spent a couple months as an exchange student in Mexico and I was really lonely. I practiced all the time. Beyond any sound it was producing, it became a method of coping for me. As a result, I really learned the instrument. It became very useful for me to be in another world and it still is. I like this other world and I stay in it as often as possible.

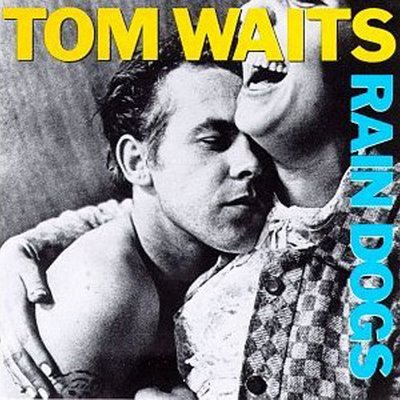

PHAWKER: Eventually you came out of the room to play guitar for others and you’ve since gone on to connect with a variety of artists, including Tom Waits. As a huge fan, I’m curious how did that meeting happen?

PHAWKER: Eventually you came out of the room to play guitar for others and you’ve since gone on to connect with a variety of artists, including Tom Waits. As a huge fan, I’m curious how did that meeting happen?

MARC RIBOT: Tom was in New York during the period of making Rain Dogs and a few years before that. I think he was actively researching music in New York. He came there specifically to check out what was happening on the underground scene, which in the early 80s was inhabited by the Punk/Post-punk/No-Wave sound. I remember that Tom heard me play with two different bands. One was Brenda and the Real Tones and the other was John Lurie’s Lounge Lizards. He saw me with the Lizards a couple times, once during New Years Eve he sat in with us and sang Auld Lang Syne. We were all so amazed how this sound came out of this skinny little guy. So he heard me with The Lizards and called me up to play on Rain Dogs. I was one of a number of guitarists on that record. We got along and he asked me to come on the tour and sometimes he’s called me since then.

PHAWKER: Some critics and fans note jazzy elements in Tom Waits’ music. For those naysayers who disagree, those who feel the avant-garde or free movements aren’t “jazz”, where do you fall on that?

MARC RIBOT: I don’t see it as my position to define where I fall; I leave that to others. I’m not against it; jazz is a very big word, it covers a lot of histories. I have great affection for some of those histories, and others I just don’t care about at all. I’m very interested in a lot of the players that came out of the free jazz movement in particular Albert Ayler. Many critics did not accept him as jazz during his life; they preferred to call it a type of spiritual music or noise. He wasn’t canonized as a jazz player until fairly recently. I’m interested in that intensity and that process of playing. The way they would do a tune then just completely dive off the deep end into improvising as opposed to following the tempo or harmony that was played during the melody, which is what bebop players did. They would improvise on the pre-existing harmonies of the tune. Whereas with Aylers’ group, the harmonics they did were that much wider than bebop, they included noise elements, improvising like a twelve-tone player would, like a serial classical musician and at the same time, they’d use polyphony that a New Orleans musician may have used. Instead of having the soloist be free or the rhythm section being locked into quarter note walking bass, everybody in the band was doing counter-melodies. Also, Ayler’s compositions, harmonically, used Cuban and rock and roll chord elements. There’s a lot I found useful in that.

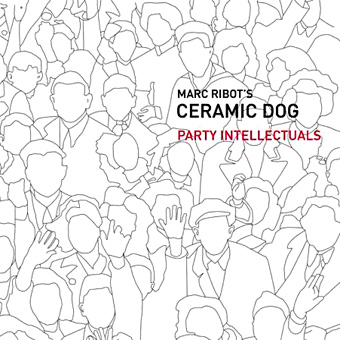

PHAWKER: I’m curious about the name Ceramic Dog, it makes me think of a ceramic sculpture on someone’s lawn, seems cute, harmless and kitschy. However the music you all make has considerable bark and bite.

MARC RIBOT: It came from the French expression “chien de faïence,” meaning frozen with emotion. The French don’t think of a ceramic dog as a kitsch sculpture, they think of a dog frozen perfectly still the moment before it’s gonna spring and tear your throat out. We thought it was funny.

PHAWKER: From what I understand, Ceramic Dog was born out of a desire to do away with hyphenated labels and to dive deeper into a boundary-free  sound that embraces collective improvisation. How would you describe what you’re pursuing with this project?

sound that embraces collective improvisation. How would you describe what you’re pursuing with this project?

MARC RIBOT: We just try to rock the house. We are two things: we are a rock band and a collective. Unlike any of my other projects, we rehearse as often as we can just because we like to. The band is based on the personalities of the three players. There’s bassist Shahzad Ismaily, drummer Ches Smith and myself. If either or both of those guys couldn’t make a gig, there’s no calling a substitute. It’s a real collective, we share stuff, write tunes together and for me, that’s been a lot of fun not having to be the bandleader so to speak. We share the responsibilities in that way. Plus, I love both of their playing. Ches is jazz trained, but he clearly comes from a Deerhoof, post-punk indie rock scene. Both grew up with some kind of extreme rock be it hardcore, straight edge or whatever and then became interested in composition, but didn’t stop being rockers because of that. Shahzad and I met on an improvisation gig, an electronica type improv, and he’s worked with countless New York bands and brings a great, anarchic sensibility to all of them. They’re both improvisers, neither of whom comes from a primarily jazz background. Our performances are a mixture of improvised as well as tunes we’ve rehearsed once or twice.

LOS CUBANOS POSITIZOS: No Me Llores Mas