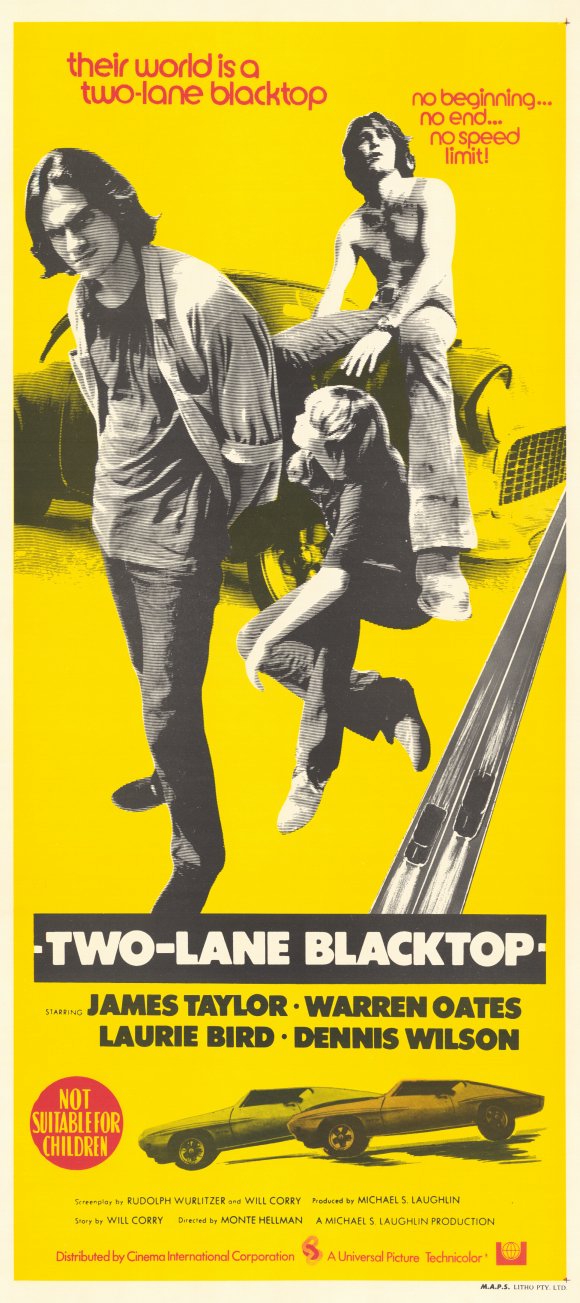

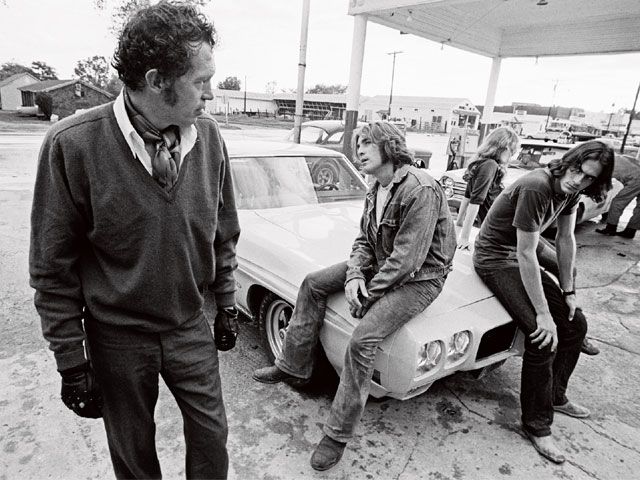

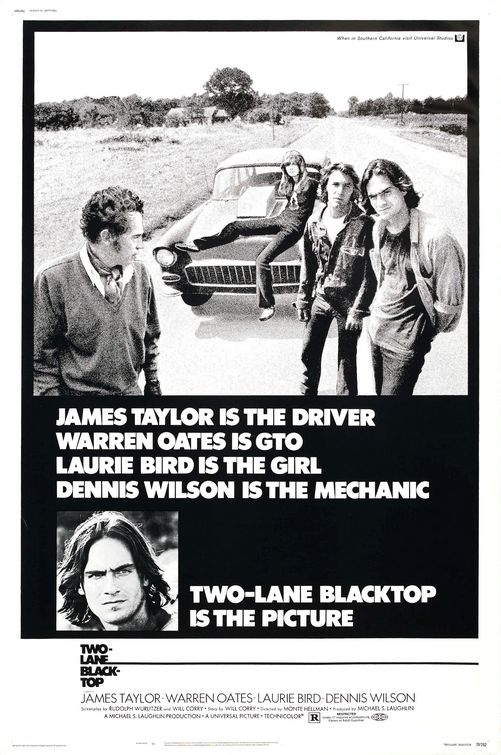

BY ALEX POTTER Two-Lane Blacktop, starring a pre-fame James Taylor and a post-fame Dennis Wilson, has been called the quintessential road movie. The mysterious, stoic and taciturn Driver (the progenitor of Ryan Gosling’s The Driver character in Drive?) is played by Taylor and his equally mysterious and stoic sidekick, The Mechanic, is played by Wilson. Director Monte Hellman, who went on to co-produce such celebrated indie films such as Reservoir Dogs and Buffalo ’66, deliberately selected non-actors to portray the Driver and the Mechanic. Robert de Niro, Al Pacino and James Caan were all interested in the role that the cult director eventually gave to the 23 year-old Taylor.

BY ALEX POTTER Two-Lane Blacktop, starring a pre-fame James Taylor and a post-fame Dennis Wilson, has been called the quintessential road movie. The mysterious, stoic and taciturn Driver (the progenitor of Ryan Gosling’s The Driver character in Drive?) is played by Taylor and his equally mysterious and stoic sidekick, The Mechanic, is played by Wilson. Director Monte Hellman, who went on to co-produce such celebrated indie films such as Reservoir Dogs and Buffalo ’66, deliberately selected non-actors to portray the Driver and the Mechanic. Robert de Niro, Al Pacino and James Caan were all interested in the role that the cult director eventually gave to the 23 year-old Taylor.

But the real star of the movie is not a Beach Boy or an up-and-coming laid-back singer-songwriter — it’s a 1955 Chevy 150 two-door sedan with no paint-job, a souped-up engine and an extra-light, aluminum shell. We know this because “The Car” makes an appearance before the “main characters” do. In the first scene, just moments before the checkered flag is waved, we see Wilson, “the Mechanic,” frantically inspecting the contents underneath the hood before the Driver speeds away. One can barely tell it’s the  drummer from The Beach Boys. Then we get a glimpse of a stoic James Taylor in the driver’s seat, entranced by the cacophony of roaring engines, the only noise that passes for dialogue in the first five minutes of the film, preparing for competition and strapping on his safety harness.

drummer from The Beach Boys. Then we get a glimpse of a stoic James Taylor in the driver’s seat, entranced by the cacophony of roaring engines, the only noise that passes for dialogue in the first five minutes of the film, preparing for competition and strapping on his safety harness.

Taylor’s Driver has just two things on his mind: winning a cross-country race against “G.T.O.”, played by the avuncular Warren Oates, and winning the heart of the Girl, portrayed by the wild-at-heart Laurie Bird. Both competitions take unpredictable turns, and the film transforms quickly from a simple drag-racing flick to a dizzying, artsy, high-speed odyssey. Like a good epic, the reward is in the journey, not the destination and the travelers take many unexpected detours. They begin at Lake Tahoe in Northwest California, and drive south through Nevada. There, at a café, while Taylor and Wilson replenish themselves, the Girl, played by Laurie Bird in one of only three films she made in her tragically short life (she committed suicide at the age of 25), makes one of the most unassuming and yet emblematic entrances in film history. If you’re not paying attention, you’ll miss her disembarking from a van in the café parking lot and sauntering two spaces down where she decides she likes the gray ’55 Chevy enough to take her chances with whoever drives it. It’s a marvelously subtle take on the culture of hitchhiking in the 1960s and ‘70s. The boys climb back into the hotrod and barely take notice of her presence. A small smile appears on the lips of Taylor as he turns around to back out, perhaps the only moment in the film in which he shows emotion. The Girl asks them, “You aren’t the Zodiac Killers are you?”

They’re not criminals, but they are outlaws (racing is illegal, after all) and they live life just a cut above deprivation. When it gets cold, the girl asks the Driver to turn on the heat and he explains to her that they don’t have a heater because it slows a car down. At one point, Wilson instructs Taylor to eat light because “hunger is good” when you have a long drive ahead of you. They only use about one tenth of their bank for food, anyway. When the boys run out of cash, they race for money invariably win. Still, they often find themselves in dire straits and, in Santa Fe, they send the Girl out to panhandle for money. In a creative aerial shot, Hellman follows Laurie Bird as she walks innocently toward the sidewalk where rich tourists are roosting. Because this scene was an unwritten, candid take, one can genuinely feel the shame and awkwardness of the act of begging. The tourists, who were real and ignorant of the cameras recording them look at her like she’s a lost soul, another victim of the morality-depraved ’60s.

Later that night, the Driver challenges the owner of a 1932 Ford, who says he’ll race for $50. “Make it three yards motherfucker,” says the one and only Sweet Baby James, “and we’ll have an automobile race.” The movie is worth the price of admission just to watch James Taylor utter that line. More exchanges of braggadocio and testosterone soon follow with Warren Oates, who charges into the film as suddenly as one the many hitchhikers that get into his car along the way. He passes by the boys in the left lane and stares them down, daring them to take his canary-yellow Pontiac G.T.O. on in a rubber-burning competition. In a shirt and pullover, he looks like a fish out of water in his flashy machine, the polar opposite of the Car. He won his, as a matter of fact, in a card game in Las Vegas. At least twice the age of the boys in the Chevy, he comes off as feeling inadequate and over the hill; the look on his face is one of jealousy and fear.

Later that night, the Driver challenges the owner of a 1932 Ford, who says he’ll race for $50. “Make it three yards motherfucker,” says the one and only Sweet Baby James, “and we’ll have an automobile race.” The movie is worth the price of admission just to watch James Taylor utter that line. More exchanges of braggadocio and testosterone soon follow with Warren Oates, who charges into the film as suddenly as one the many hitchhikers that get into his car along the way. He passes by the boys in the left lane and stares them down, daring them to take his canary-yellow Pontiac G.T.O. on in a rubber-burning competition. In a shirt and pullover, he looks like a fish out of water in his flashy machine, the polar opposite of the Car. He won his, as a matter of fact, in a card game in Las Vegas. At least twice the age of the boys in the Chevy, he comes off as feeling inadequate and over the hill; the look on his face is one of jealousy and fear.

Condemned to a life on the road for reasons Hellman and his writers never really explain, G.T.O. depends on the hospitality of his temporary passengers for human connection. Hitchhikers come and go: A Texas businessman in a ten-gallon hat, an elderly woman and her granddaughter, and a despondent Harry Dean Stanton are just a few of the many who flag down G.T.O. Oates puts on a show for them all, enchanting few and disturbing many with an arrogance he tries to pass off as charm. The boys’ and G.T.O.’s keep crossing paths: first in Nevada, then New Mexico, and finally in Texas, where the Driver acknowledges him and decide Oates would be an easy mark. They hammer out a deal: the first to Washington, D.C. wins the other’s vehicle. They put their pink slips in the mail to seal the compact. There turns out to be more at stake than just fast cars, however.

Two-Lane Blacktop is not about racing. If you’re looking for Fast and the Furious or Gone in 60 Seconds, don’t rent this movie. Watch Blacktop if you like moody performances and don’t care about plotlines going off course faster than a 454 horsepower hotrod. Plot questions mostly go unanswered. In fact, in one scene in which Oates rides with Taylor while the Mechanic temporarily drives the G.T.O., Taylor cuts Oates off when the older man starts talking about his past life as a television producer. “I don’t care,” the Driver tells him. “It’s not my problem.” Sympathy is a luxury he simply cannot afford.

The Movie itself becomes what life on the road must be like: the passing by of significant events without a second thought. At one turn, a driver full of road-rage tries to pass the Driver, who refuses to let him go by. The stranger chases him for a few miles until Taylor speeds off the road into the dirt to avoid the aftermath of a fatal collision. When the driver stops the Car, Wilson jumps out and the first thing he does, of course, is check the front axle for damages. Meanwhile the Girl meanders out of the car, dizzy and shocked from the sudden departure from the road. It’s only then that the boys notice her. This negligence will come back to haunt them.

The crash itself is grisly: a truck turned over on its side, a bloody dead body dumped out onto the asphalt, the survivor, a truck driver, pacing back and forth in grief and desperation. The Driver doesn’t say a word, and walks away from it like any other piece of roadkill. The end of the film lacks a catharsis, which is the point. The girl exits the same way she enters, choosing none of the three drivers to ride with, in the end. A muted, slow motion ending shot of Taylor from the back of the car disintegrates as the film literally melts into black and the credits roll. The last thing one thinks of is the Driver ending up exactly like empty, rootless, old G.T.O., running on fumes and dying just like he lived: alone.