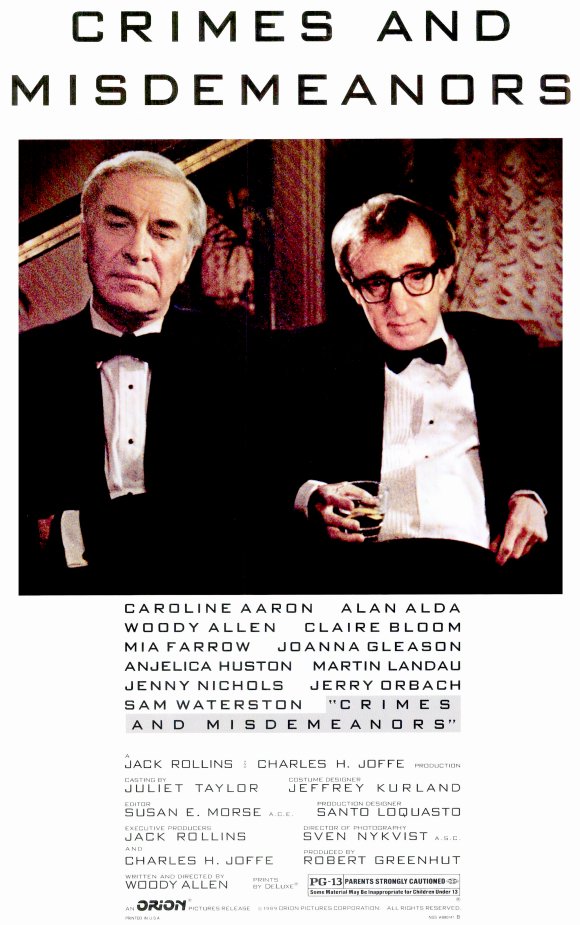

BY ALEX POTTER With the new Midnight in Paris enjoying generous commercial and critical success, many critics are looking back on Woody Allen’s career and asking themselves when Allen last executed something so well. Crimes and Misdemeanors, originally released in 1989, appears to be the consensus. Crimes is two stories that have nothing but the theme of adultery and a blind rabbi in common. Martin Landau plays Judah, a successful ophthalmologist, and Allen, the unsuccessful filmmaker, Cliff. Both men have reached breaking points in their marriages. Many people may find that the two narratives, which could stand alone as two short films, when fused together, don’t equal a cohesive whole, but the final scene puts everything in perspective. When Cliff and Judah sit side by side at a wedding reception apart from everybody else, one can surmise that each would happily switch places with the other, unless they knew each other’s dark secrets.

BY ALEX POTTER With the new Midnight in Paris enjoying generous commercial and critical success, many critics are looking back on Woody Allen’s career and asking themselves when Allen last executed something so well. Crimes and Misdemeanors, originally released in 1989, appears to be the consensus. Crimes is two stories that have nothing but the theme of adultery and a blind rabbi in common. Martin Landau plays Judah, a successful ophthalmologist, and Allen, the unsuccessful filmmaker, Cliff. Both men have reached breaking points in their marriages. Many people may find that the two narratives, which could stand alone as two short films, when fused together, don’t equal a cohesive whole, but the final scene puts everything in perspective. When Cliff and Judah sit side by side at a wedding reception apart from everybody else, one can surmise that each would happily switch places with the other, unless they knew each other’s dark secrets.

Judah is the Dostoevskian anti-hero. He has been having an affair with a flight attendant for two years. Angelica Huston [pictured below, right], who is known for her icy cool, (SEE her roles in three Wes Anderson films) plays the neurotic, unpredictable Dolores. When Judah fails to make good on some foolish promises he’s made to her, Dolores threatens to tell Miriam, his wife of 25 years, about the affair. Dolores is also the only other human being who knows about some embezzling Judah has done and is deeply ashamed about. Judah, who’s in the twilight of his career, has decided there’s too much at stake. He’s just given his daughter away to her husband and opened a new ophthalmology wing in a hospital. Needless to say, he has a lot to lose, which is why he hires his mobbed-up brother Jack to kill her.

Cliff is the Danny DeVito to Judah’s Arnold Schwarzenegger. He’s basically a man-child who can’t get over the fact that the movie industry is also a cutthroat business. His boss and brother-in-law, the egomaniacal TV producer Lester, played beautifully by a smarmy Alan Alda, fires Cliff for turning the documentary he was supposed to make about Lester into a mockumentary. His marriage to Wendy (Joanna Gleason) has turned platonic. By the way she treats him—flatly denying him sex, going through the motions—one would think she’s cheating on him. Perhaps she wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of grounds for a divorce. Cliff, however, is the one with his eyes on another woman: Halley or, the female version of Cliff, played by Allen’s wife at the time, Mia Farrow. They meet working together on the ill-fated Lester hagiography and wind up sharing a tender kiss, but Cliff doesn’t have the gumption to take it to the next level, unlike Judah.

Lester happens to have the hots for Halley, as well, creating an incestuous web of resentment and desire. Bad jokes about Oedipus made by Lester while attempting to explain the science of writing comedy are not coincidental. Almost everybody is involved in some sort of scandalous or perverted affair. In a darkly hilarious scene Cliff’s own sister, Barbara, tells him about a date she went on with a man she found in the personal ads who actually gave here a Cleveland Steamer. Cliff himself finds the only person he can be completely open with (and not worry about getting harmed or judged by) is his thirteen year-old niece, Jenny. They go to matinee movies together and he tells her about all his personal problems. Allen couldn’t get away with this now, of course, even though his own marriage to his once-adopted daughter is slowly getting less creepy with age.

attempting to explain the science of writing comedy are not coincidental. Almost everybody is involved in some sort of scandalous or perverted affair. In a darkly hilarious scene Cliff’s own sister, Barbara, tells him about a date she went on with a man she found in the personal ads who actually gave here a Cleveland Steamer. Cliff himself finds the only person he can be completely open with (and not worry about getting harmed or judged by) is his thirteen year-old niece, Jenny. They go to matinee movies together and he tells her about all his personal problems. Allen couldn’t get away with this now, of course, even though his own marriage to his once-adopted daughter is slowly getting less creepy with age.

The most fascinating elements of the film are Judah’s and Cliff’s elusive and somewhat dubious sources of morality. Judah has memories of his fastidious rabbi father and Cliff takes guidance from the subject of another documentary he has been working on for years: Louis Levy, a fictional psychologist who combines Freudian theory with Existentialist philosophy and shares his moving opinions on the puzzling phenomena of human life and love and death. The ghost of “Papa” tells Judah as a boy, “The eyes of God see all. There is absolutely nothing that escapes his sight. He sees the righteous and he sees the wicked. And the righteous will be rewarded, but the wicked will be punished for all eternity.” Judah makes a mockery of the notion that bad deed goes unpunished as he unveils the new ophthalmology wing named after him at a dedication ceremony, joking that it was simple fate he turned out to be an eye doctor. Landau’s own eyes are glassy and haunted, and not for nothing did he receive an Oscar nomination for what is arguably one of the most indelible performances his long and storied career. “God is a luxury I can’t afford,” he says aloud just as he decides to move forward with the murder. He doesn’t believe in the eyes being the window to the soul until he sees Dolores staring at him blankly, dead on the floor.

Levy, Cliff’s personal god/father figure, believes “the universe is cold, and humans invest their feelings in it. When there’s nothing left to feel, there is no longer any point to living.” The old sage, surprisingly but perhaps fittingly, commits suicide, completely upending the philosophical foundation Cliff, who fails to see that at least Levy took control of his own fate. Sam Waterson, plays a patient of Judah’s named Ben, a rabbi who’s going blind. He’s also, ironically, the moral compass of the film. He tells Judah to come clean to his wife about the affair but Judah thinks this is unrealistic — that Ben lives in the “Kingdom of Heaven,” not the real world. “Merriam worships me,” Judah says, convincing himself that his wife would be crushed if her god/husband fell from grace. (Law & Order fans will thrill to see not one but two of the show’s alums: Waterson and the late Jerry Orbach who plays Judah’s gangster brother.)

It is no accident that the two protagonists — Judah who has committed a high crime, and Cliff, whose wrongdoing never really rises above misdemeanor status — never cross paths until their casual encounter in the last scene as it is indicative of Allen’s jaundiced vision of humanity: they are both prisoners of their own universes, blind to the feelings of others and incapable or uninterested in separating right from wrong — and consequences be damned.