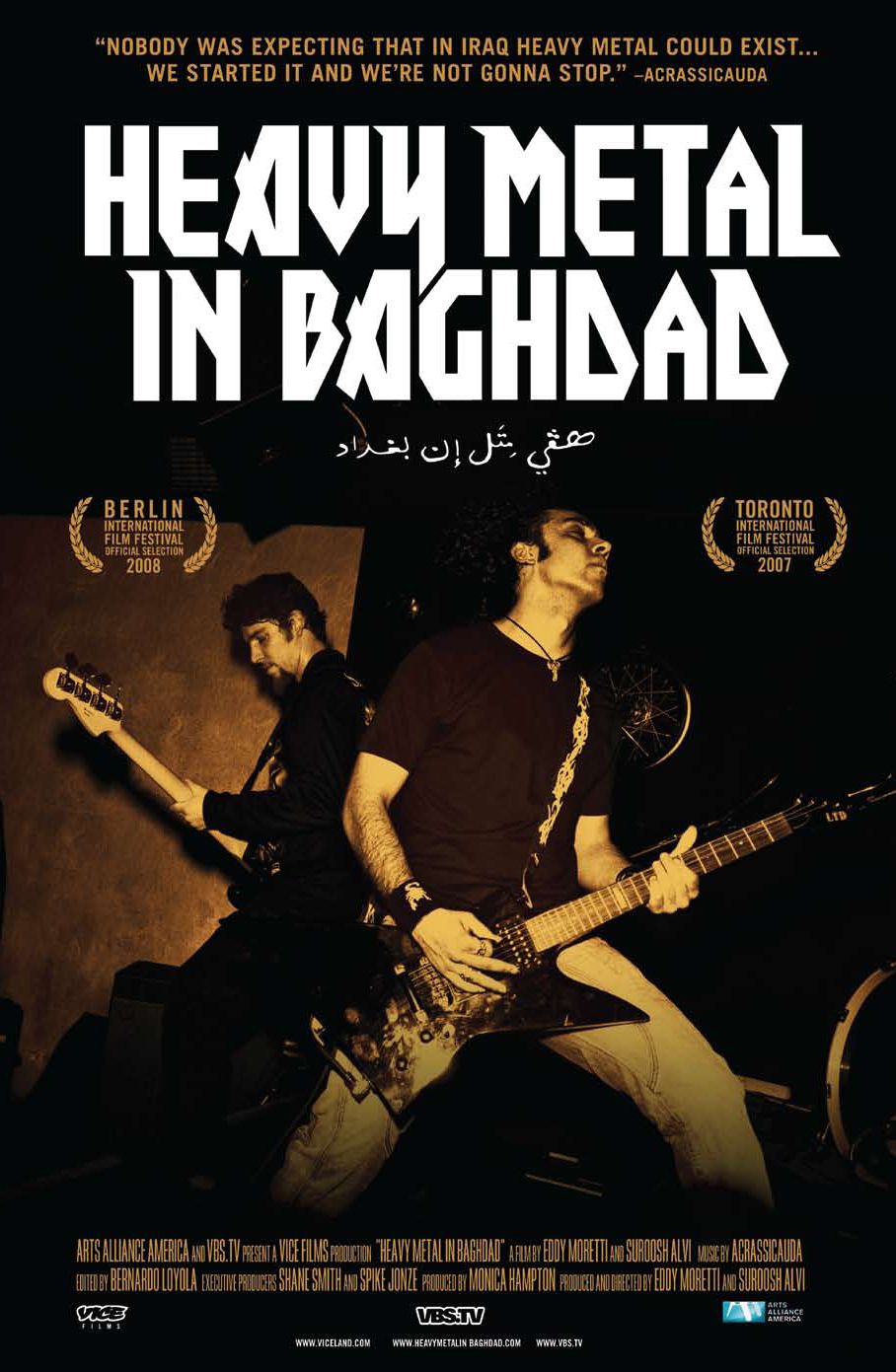

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA Baghdad metallurgists ACRASSICAUDA have survived Saddam’s thugs, al Qaeda goon squads and assorted jihadist jerks — all of whom tried to silence them, under threat of death or imprisonment — but can they survive Fish Town? Find out tonight when they rock Johnny Brendas, along with all-girl Metallica tribute band Misstallica. On the eve of a U.S. tour, we got Acrassicauda drummer Marwan Riyadh on the line to talk about life in a war zone when you’re young, Iraqi and just wanna rock the fuck out — which is easier said than done, because if American bombs don’t kill you, the insurgents probably will.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Baghdad metallurgists ACRASSICAUDA have survived Saddam’s thugs, al Qaeda goon squads and assorted jihadist jerks — all of whom tried to silence them, under threat of death or imprisonment — but can they survive Fish Town? Find out tonight when they rock Johnny Brendas, along with all-girl Metallica tribute band Misstallica. On the eve of a U.S. tour, we got Acrassicauda drummer Marwan Riyadh on the line to talk about life in a war zone when you’re young, Iraqi and just wanna rock the fuck out — which is easier said than done, because if American bombs don’t kill you, the insurgents probably will.

PHAWKER: You are currently living in New York City?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yes – in Manhattan to be exact, where I am doing my laundry as we speak.

PHAWKER: Going back to the beginning, tell me how did you first get into heavy metal music? What was the first song or album that you heard and how old were you?

MARWAN RIYADH: Growing up, my father always listened to Sinatra and Elvis around the house so when I was a kid I got introduced to Western music. When I was 14 or 15, we started looking for music ourselves and later on a friend of ours went abroad and came back with an album by Sepultura, which at first sounded just too heavy but then it sounded perfect, it was just what we needed at that time. Being a teenager in Iraq was very much difficult.

PHAWKER: You were 14 or 15 then – how old are you now?

MARWAN RIYADH: I am 26 heading into 27

PHAWKER: You grew up in Baghdad, is that correct?

MARWAN RIYADH: Correct.

PHAWKER: Where in Baghdad would you be able to get a hold of this music? Record store? Street bazaars?

MARWAN RIYADH: It was from a bunch of people who traveled outside the country — there was not a lot of people who actually like sold this stuff in the street, you know? You had to know where to go and who to ask. There was a very small metal culture in Baghdad and you had to know somebody to be included. There was a couple stores that sold records by Arabic singers, and you go and they’d sell you whatever, and then you’d be like “hey, so I heard you got like the new Slayer record” or something. And then you would see their faces and they’d be like “Oh! You’re one of us!” And that’s strange, it was really strange, but that was the way it is.

PHAWKER: And how did you meet the rest of the guys in the band? Were you friends already or did you meet in the scene?

MARWAN RIYADH: Back in ‘99 or ’98, we met through mutual friends and we had this idea to start playing music and stuff like that. The main problem was we were trying to put a band together and we didn’t have a drummer. And I was like “well, I’ll see what I can do.” My cousin used to sell musical equipment and I asked him if he could get me a drum kit and he said “that’s too expensive for you – you can’t afford it” and we’re talking about stuff from back from the 70’s that’s more like a antique. And I didn’t know what I’m getting into. It was pretty rough at first with the family, neighbors, moving the stuff – we got a little rehearsing space. Couple guys joined, couple guys left, couple guys joined, couple guys left, and a couple guys got kicked out of the band. Then we got to meet.

PHAWKER: When did the band officially get started with the current line-up?

MARWAN RIYADH: 2000-2001.

PHAWKER: And where was this first show?

MARWAN RIYADH: It was in Baghdad.

MARWAN RIYADH: It was in Baghdad.

PHAWKER: Where, a coffee shop, a performing arts venue?

MARWAN RIYADH: It was more like a gallery. They used to do paintings and stuff. So we sent out an announcement for the show, but it was very hush hush and we expected like 20-30 people to show up and 275-300 people showed up. That was major for us, and that’s when we were like, ‘OK, we’ll do more shows.’

PHAWKER: But playing Western music was kind of frowned on by the government and a lot of other people in Baghdad that weren’t too keen on the United States would also frown on that, is that correct?

MARWAN RIYADH: The first obstacle was the government. Everything was censored, but after [the American invasion toppled the government in] 2003 it was like everyone could do anything they want. But that changed with the insurgency, because at first you had only government to watch out for but later on it was everybody [that was a potential threat] basically.

PHAWKER: Did the Saddam regime actually make you give them your recordings so they could approve them or not?

MARWAN RIYADH: Well one of the shows we did in 2003, like January 2003 two months before the war, we had to go through a whole process of paperwork and stuff just to rent this [performance ] space. A guy came up to us and he was a teacher who said “you guys might get yourselves in trouble for doing this” because we’re singing English and rock and roll and stuff and we said “well, what are we supposed to do we can’t stop, we want to do it” and he was like “well try to write a song for them” and we said “a song?” So we did this [pro-Saddam Hussein] song at the start of every concert.

PHAWKER: What was the name of the song?

MARWAN RIYADH: “Youth of Iraq,” talking about, you know, how great the government is.

PHAWKER: So what do you recall about the initial days of the U.S. invasion of Iraq? Were you in Baghdad when the city was being bombed?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah, I was in Baghdad, all of us were in Baghdad and it was hard to get in touch with each other, and we didn’t know if each other was still alive. It was basically waiting for 40 days of bombing, like, are you going to die or survive? And there was no news, there was nothing to tell us what was happening just black out the whole time.

there was no news, there was nothing to tell us what was happening just black out the whole time.

PHAWKER: During the bombing of Baghdad, would you guys go to bomb shelters or was it basically you just lived your life the way you always did and hoped a bomb didn’t fall on your head?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah that was the plan, actually. We would just cross fingers and it’s funny because no we didn’t go to bomb shelters, we basically just stayed at the house. I remember my dad making me go up on the roof of the house with a broom, there was all this debris up there from missiles and explosions.

PHAWKER: The shrapnel from the bombs would land on the roof of your house and your dad would make you go on the roof and sweep it off?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah.

PHAWKER: Wow. How close did any of them land to where you were living?

MARWAN RIYADH: Ah, really close, I mean, you could sit on the floor and feel the impact vibrate from under your ass literally. Windows would break, even if we taped them and I mean it was loud – you could see the flashes you can feel the impact and the blast even if you’re in your house

PHAWKER: When did it first occur to you that the government had fallen and the Americans had taken over the city?

MARWAN RIYADH: I believe it was five days [after the start of the ground invasion] because it got real brutal and there were tanks were rolling down the street and I saw a lot of people on the tanks and I thought “this is definitely not the Iraqi army.”

PHAWKER: Were you glad at first that the Americans had invaded or not so much?

MARWAN RIYADH: I was in shock, I was indifferent to it. I was in shock after all the bombing — heavy, heavy bombing and it kept going for nearly two months. I was in shock at first and then I was worrying about the rest of the guys. I was worrying because what happened after that was people started looting stuff and just went crazy, went chaotic and you worried about your family because people were burning and looting, you know. That was at first, so you were just like in shock. Then you started to adapt — that is what our band is all about: adaptation. Whatever situation comes your way, you just need to adjust and you need to adapt to it. Even living in different countries and staying like, as a unit. It’s all about adaptation.

PHAWKER: What was scarier: Living under Saddam Hussein or living under the chaos of the insurgency that followed?

MARWAN RIYADH: With Saddam, we didn’t have a future. There was no future there was no money there was no food there was no this there was no that, everyday hopefully you have something to put on the table for dinner. I started working when I was ten years old just to support my family. That was basically the situation Saddam had set up.

MARWAN RIYADH: With Saddam, we didn’t have a future. There was no future there was no money there was no food there was no this there was no that, everyday hopefully you have something to put on the table for dinner. I started working when I was ten years old just to support my family. That was basically the situation Saddam had set up.

PHAWKER: What was the job you had when you were that age?

MARWAN RIYADH: I used to rip pages from my books or find books down the street, rip the pages and glue a flower to it and go sell them at the market.

PHAWKER: And people would buy them?

MARWAN RIYADH: Well it was like a penny.

PHAWKER: So what was life like during the insurgency, and what made you guys decide you had to leave the country?

MARWAN RIYADH: I almost died a hundred times. We got shot at, one time a bomb went off two cars away from us. That was the [final straw].

PHAWKER: This was a car bomb?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah, this bomb went off down the street close to the practice space and we were heading, and it was like two or three cars ahead of us and this [bomb] just went off. I remember the blast from the other side of the road, and even my sunglasses, like, I lost them.

PHAWKER: The blast blew the sunglasses off your face?!

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah that was funny because I thought I lost my eye…after the blast you don’t realize you can actually still see with your eyes. I was just like touching them and when I realized I wasn’t blind I realized there were all these dead bodies around me.

PHAWKER: Didn’t you start getting death threats from people, too?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah, we got it once, they tacked a message on the door where we practice at, and it was like “death for you  all if you don’t stop playing” and “we’ll get you and we’ll kill you” and stuff like that. We kept practicing, though. I guess in some ways we were like, insane, we were just making jokes about it, like “watch the door open up and somebody throws in a grenade and closes the door back.”

all if you don’t stop playing” and “we’ll get you and we’ll kill you” and stuff like that. We kept practicing, though. I guess in some ways we were like, insane, we were just making jokes about it, like “watch the door open up and somebody throws in a grenade and closes the door back.”

PHAWKER: Well that kind of stuff happened, too, all the time, right?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah, I guess when you’re like 18 or 19 fucking everything seems like metal, it’s all so metal, it’s so cool. You didn’t realize you were jeopardizing your life and your family’s life, too, and these guy’s lives. Putting everything on the line for a song.

PHAWKER: It’s no different in the United States, although the danger isn’t quite as high as you experienced there, but that’s common for people when they’re teenagers or young men to think they are “bulletproof.”

MARWAN RIYADH: Exactly, that’s exactly the same feeling. Now we look at it from a totally different perspective, like “wow, how did we do that without dying?”

PHAWKER: Now, eventually it got so bad you guys decided you had to leave Baghdad, is that correct?

MARWAN RIYADH: Uh-huh.

PHAWKER: What year was that?

MARWAN RIYADH: 2006.

PHAWKER: Didn’t you all go to Syria, is that the deal?

MARWAN RIYADH: We all went to Syria, Damascus, and that’s when we got reunited again and we played a couple shows – six people showed up.

PHAWKER: Six?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah, basically it was like my roommates and the other guy’s roommates.

PHAWKER: How did you find places to stay? I mean, when you leave Baghdad, I mean, when you leave Iraq and just show up in Syria how do you find a place to stay or live or get a job or what?

MARWAN RIYADH: First I stayed in a one room apartment, you know like a very small room with one bed and one couch and five other guys, and I just stayed there for two months and I lost my mind. After that we moved into someone’s basement because that was all we could afford, but at least we were all together.

PHAWKER: Have you been following the developments in Syria in the last few weeks?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah.

PHAWKER: What do you make of all that?

MARWAN RIYADH: Well, you know what, I just try to focus on music because politics is just a game of the rich. I guess the working class people; they’re always the ones who have to make sacrifices first. The rich people start the wars and the poor people are the ones who die. Before I looked at it different, now I think it’s all the same wherever you go. Whether you’re an American citizen who lives and works for generations, or an Iraqi or whatever working in different circumstances and different environments you’re still a work class person – you’re the one whose going to make sacrifices first. Not the rich and powerful. For me the way I look at it, what are you going to get out of it? Nothing. I think war for [the rich] is needed, because this is what they feed off.

PHAWKER: And so you’re saying that you think even if the Assad regime fell, life wouldn’t be better for people in Syria? There’d just be a new dictator to come in?

MARWAN RIYADH: There’s always hope. Always hope for the best otherwise we wouldn’t be living right now. There is always hope and a light at the end of the tunnel that hopefully those people will be free and able to practice their life and live decently. It’s what they deserve, because when you work seven days a week 12 hours a day and you only get paid like 100 dollars a week, this is not fair, this is not right. And the minute that you give the people what they want then you’re free but even freedom has its own  price. A lot of people paid for it, I mean, all these wars, and a lot of people pay for it with their religion or their homeland but it’s the government that gets the most out of it.

price. A lot of people paid for it, I mean, all these wars, and a lot of people pay for it with their religion or their homeland but it’s the government that gets the most out of it.

PHAWKER: Are you a practicing Muslim?

MARWAN RIYADH: Well that’s the thing. We’re musicians – that’s what we do most of the time. Religion and politics we try to stay away from…it’s very complicated let me put it this way… I don’t want to give opinions about this stuff.

PHAWKER: Fair enough. So, eventually you guys had to leave Syria because… why? You had a limited visa?

MARWAN RIYADH: Well the government initiated this thing about kicking out Iraqi refugees — there were over a million or two million in Syria. Plus it was about time because we weren’t doing anything in Syria.

PHAWKER: You weren’t able to play or do concerts in Syria?

MARWAN RIYADH: No we weren’t able to play in Syria. So, we had to leave, and that’s when, actually, we met the guys from Vice and they helped us raise donations for the band and this is how we got out of Syria and got to Turkey, Istanbul.

PHAWKER: I’m sorry, who raised donations?

MARWAN RIYADH: Vice Magazine. We were doing a documentary and they heard about it and set up a Paypal and said ‘we’ll try to raise donations for you’ and surprisingly it worked. People from all different places in the world donated money for us, and it was overwhelming.

PHAWKER: That’s great. So from there you went to Turkey and eventually came to the United States?

MARWAN RIYADH: Yeah.

PHAWKER: Okay and you are all currently living in the United States?

MARWAN RIYADH: All of us, yeah.

PHAWKER: Great – are you all in New York?

PHAWKER: Great – are you all in New York?

MARWAN RIYADH: No two guys in Georgia, one guy was in Virginia he just got back for the tour, and we’re in New York right now.

PHAWKER: What do you have, a work visa? What is your status here? Are you citizens?

MARWAN RIYADH: I have a green card.

PHAWKER: And that allows you to stay here for how long?

MARWAN RIYADH: A green card is ten years, but after seven years you become a citizen.

PHAWKER: Excellent. One last question, do you have an opinion one way or another about the killing of Osama bin Laden?

MARWAN RIYADH: Well, you know what, honestly the only reason we survived through all this is because we don’t give any opinions about this stuff. I mean, this is like an endless, endless puzzle for me, I mean, like, we try to stay musicians and work at it this way because we have a lot of things to worry about so I don’t want to say we’re kind of like indifferent about this situation because we’re not, but I just wish this thing comes to an end and is all over – I don’t want to sound hippie about it, but we hope for an end, and people can actually work on something better.

PHAWKER: Amen, brother.