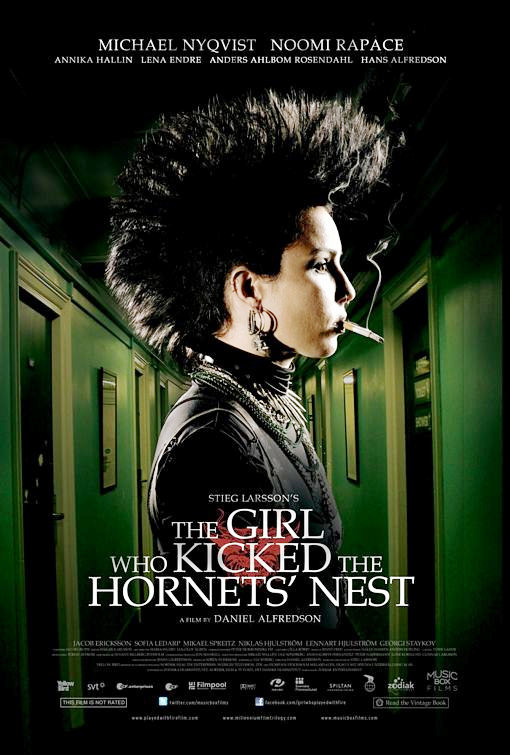

THE GIRL WHO KICKED THE HORNET’S NEST (2009, directed by Daniel Alfredson, 147 minutes Sweden)

FOUR LIONS (2009, directed by Chris Morris, 97 minutes, U.K.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

I was a little disappointed that the title of this third film from the best selling Stieg Larsson novels was only metaphoric. In the first part, hacker and violent avenger Lisbeth Salander really showed her dragon tattoo and in the second half she actually played with fire (engulfing her abusive daddy in flames). Here, I was hoping for some Wily Coyote-style action where Lisbeth made one of her many attackers wear a bee hive like an Easter bonnet. Alas, I didn’t get what I wanted, and in fact the last film of this trilogy fails to pay off in ways that would help justify our interest in this junky if occasionally engrossing Swedish crime drama.

In the last chapter, Lisbeth finally confronted Zalachenko, the man who was behind the shadowy government group “the Section” as well as being the father she lit on fire as a child. In the ultimate in “tough love” parenting, Zalachenko shot Lisbeth in the head and dumped her in a shallow grave, but she rose up and planted an axe into his noggin. This leads us to Hornet’s Nest’s opening, where both Lisbeth and her father have survived their head wounds and are recovering in the same hospital. When Lisbeth’s wounds heal, she will be placed on trial for attempted murder.

Directed by Daniel Alfredson, who mounted the previous chapter, Hornet’s Nest is too much like a European TV crime drama: short on style and action and leaden with needless exposition. On the trail to clear Lisbeth’s name is magazine publisher Mikael Blomkyist (Michael Nyqvist), and much of the film’s running time is taken up with him discovering the name of a suspect in the plot, confronting the guarded suspect then finding the next suspect in the chain, and repeat. None of this really separates “The Section” from similar shady crime conspiracies that haunt so much detective fiction; for all the investigation, their motivations and their reach remain vague.

What’s more frustrating is how the film shies away from drama at every turn. Lisbeth’s father survives her axe’s whacks and ends up at her hospital, yet they never see each other again before he is casually dispatched. Watching the slight and vulnerable Lisbeth unleash creatively violence for all the abuse she has suffered is one of the series’ main joys, yet in this chapter, she is mostly disabled by her injuries. The non-action builds to a court trial where Lisbeth faces her attackers, but watching the preposterous proceedings (where lawyers are regularly allowed to surprise the prosecution with unregistered evidence) rehash everything we’ve learned over the last six hours, making for an pretty anticlimactic climax.

Thankfully, Lisbeth is allowed to raise havoc with a nailgun in the film’s post-script so we can be roused from our sleep before this long journey is over. All would be lost if it weren’t for Noomi Rapace in the title role. Her near-silent performance is so rich and deeply felt, it makes David Fincher seem like a fool for not casting her in the forthcoming U.S. remake. At least the conclusion of this trilogy gives optimism that Fincher can create an American remake that won’t blasphemy an art house hit but actually better it.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Four Lions is an impossible film: how can a movie be expected to not only make us laugh at a group of Jihadist suicide bombers, but to make us empathize with them as well? Directed and co-written by the razor-sharp British satirist Chris Morris (known for the controversial fake investigative news show, Brass Eye) Four Lions is a pitch black, pitch-perfect comedy that aims to de-booglarize our terrorist boogiemen while enacting our worst fears. Morris’ ability to juggle all these unsettled emotions and avoid unfair stereotypes, while never missing a laugh, raises this bold film into the comic masterpiece strata.

Omar (Riz Ahmed), a young married father, is the brains of this none-to-brainy group. Ahmed possesses large and somewhat sorrowful eyes, which wring a humorous disbelief at the quality of soldier with which he finds himself paired. The other members include his easily-led best friend Waj (Kayvan Novak), the nervous explosives expert Faisal (Adeel Akhtar), the blustery Muslim convert Barry (Nigel Lindsay) and Hassan (Arsher Ali), who likes to rap about jihad. They are already in the early stages of deciding a proper place to bomb at the film’s opening and Morris doesn’t dig too deep to explain or justify their violent plans. It’s not religion; they condescend to the peaceful mosque-goers in their community. The wanna-be crime gang is poor but not really impoverished. Watching their hilarious macho posturing over who is more committed to their vague cause, you get the idea that it is ego more than ideology that is propelling this shaky venture.

But will people come to see a film about our most derided and despised foes? Morris is incredibly canny as a storyteller, he only asks us to laugh at these bickering jihadis in the opening hour. It is only as the stakes are raised in the film’s final act that we realize the affections we’ve been building for these misguided fools.

The fact that our main characters are planning to take out innocent civilians as part of their mission makes this comedy feel like nothing we’ve ever seen before. Yet at its heart, the film’s set-up is not far removed from the type of 1950’s Ealing comedies made with Alec Guiness; much like the heist planned in The Lavender Hill Mob, it’s a group of bumblers dodging the police in the service of a foolhardy plan. Co-written with two writers from last year’s political comedy In The Loop, Four Lions shares a dialog that is thick with preposterous reasoning and witty rejoinders but where In The Loop built to a non-event, Four Lions finally has to do something with the five fuses they’ve lit. In the end, each detonation is both a punchline and a tragedy and the audience leaves the theater with the unresolved emotions that makes this masterful film reverberate with the impact of a modern classic.