NEW YORK TIMES: With the mournful gong of a Buddhist temple bell and the release of a flock of doves, a crowd of 55,000 on Friday solemnly marked the moment 65 years ago when the world’s first atomic attack incinerated this city under a towering mushroom cloud. For first time, a representative of the United States, Ambassador John V. Roos, participated in the annual ceremony, raising hopes here of a visit soon by a more prominent guest, President Obama, who is scheduled to be in Japan in November. Mr. Obama has become a popular figure here since his speech in Prague last year calling for the for elimination of nuclear weapons. The mayor and other residents of Hiroshima have offered him repeated invitations to come to their city, which — along with Nagasaki — has become one of the world’s most recognized symbols of the horrors of nuclear war. American officials have traditionally skipped the annual ceremony, fearing their presence would renew the debate over whether the United States should apologize for the World War II bombings, which together killed more than 200,000 people in explosions so intense that many victims were simply vaporized, leaving only ghostly shadows on walls, while others died in slow agony from burns and radiation sickness. MORE

WIKIPEDIA: Hiroshima was the primary target of the first nuclear bombing mission on August 6, with Kokura and Nagasaki being alternative targets.  August 6 was chosen because there had previously been cloud over the target. The B-29 Enola Gay, piloted and commanded by 509th Composite Group commander Colonel Paul Tibbets, was launched from North Field airbase on Tinian in the West Pacific, about six hours flight time from Japan. The Enola Gay (named after Colonel Tibbets’ mother) was accompanied by two other B29s, The Great Artiste which carried instrumentation, commanded by Major Charles W. Sweeney, and a then-nameless aircraft later called Necessary Evil (the photography aircraft) commanded by Captain George Marquardt.[21]

August 6 was chosen because there had previously been cloud over the target. The B-29 Enola Gay, piloted and commanded by 509th Composite Group commander Colonel Paul Tibbets, was launched from North Field airbase on Tinian in the West Pacific, about six hours flight time from Japan. The Enola Gay (named after Colonel Tibbets’ mother) was accompanied by two other B29s, The Great Artiste which carried instrumentation, commanded by Major Charles W. Sweeney, and a then-nameless aircraft later called Necessary Evil (the photography aircraft) commanded by Captain George Marquardt.[21]

After leaving Tinian the aircraft made their way separately to Iwo Jima where they rendezvoused at 2440 m (8000 ft) and set course for Japan. The aircraft arrived over the target in clear visibility at 9855 m (32,000 ft). On the journey, Navy Captain William Parsons had armed the bomb, which had been left unarmed to minimize the risks during takeoff. His assistant, 2nd Lt. Morris Jeppson, removed the safety devices 30 minutes before reaching the target area.[21]

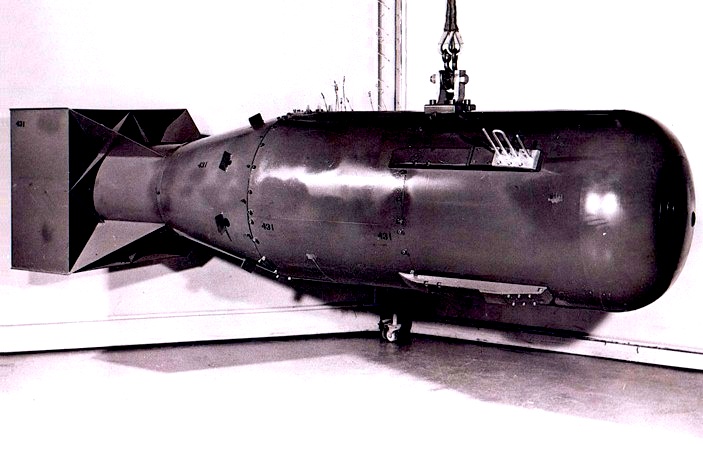

The release at 08:15 (Hiroshima time) was uneventful, and the gravity bomb known as “Little Boy“, a gun-type fission weapon with 60 kg (130 pounds) of uranium-235, took 57 seconds to fall from the aircraft to the predetermined detonation height about 600 meters (2,000 ft) above the city. It created a blast equivalent to about 13 kilotons of TNT (the U-235 weapon was considered very inefficient, with only 1.38% of its material fissioning),[22]The radius of total destruction was about 1.6 km (1 mile), with resulting fires across 11.4 km (4.4 square miles).[23] Infrastructure damage was estimated at 90 percent of Hiroshima’s buildings being either damaged or completely destroyed.

About an hour before the bombing, Japanese early warning radar detected the approach of some American aircraft headed for the southern part of Japan. An alert was given and radio broadcasting stopped in many cities, among them Hiroshima. At nearly 08:00, the radar operator in Hiroshima determined that the number of planes coming in was very small, probably not more than three, and the air raid alert was  lifted. To conserve fuel and aircraft, the Japanese had decided not to intercept small formations. The normal radio broadcast warning was given to the people that it might be advisable to go to air-raid shelters if B-29s were actually sighted, but no raid was expected beyond some sort of reconnaissance.

lifted. To conserve fuel and aircraft, the Japanese had decided not to intercept small formations. The normal radio broadcast warning was given to the people that it might be advisable to go to air-raid shelters if B-29s were actually sighted, but no raid was expected beyond some sort of reconnaissance.

As a result of the blast an estimated minimum 90,000 people died within two months.[24] Included in this number were about 2,000 Japanese Americans and another 800-1,000 who lived on as hibakusha, a Japanese term meaning, “explosion-affected people”. As US citizens, many were attending school before the war and had been unable to leave Japan.[25] It is likely that hundreds of Allied prisoners of war also died.[26]