NEW YORK TIMES: The documents — some 92,000 reports spanning parts of two administrations from January 2004 through December 2009 — illustrate in mosaic detail why, after the United States has spent almost $300 billion on the war in Afghanistan, the Taliban are stronger than at any time since 2001. As the new American commander in Afghanistan, Gen. David H. Petraeus, tries to reverse the lagging war effort, the documents sketch a war hamstrung by an Afghan government, police force and army of questionable loyalty and competence, and by a Pakistani military that appears at best uncooperative and at worst to work from the shadows as an unspoken ally of the very insurgent forces the American-led coalition is trying to defeat. The  material comes to light as Congress and the public grow increasingly skeptical of the deepening involvement in Afghanistan and its chances for success as next year’s deadline to begin withdrawing troops looms. The archive is a vivid reminder that the Afghan conflict until recently was a second-class war, with money, troops and attention lavished on Iraq while soldiers and Marines lamented that the Afghans they were training were not being paid. The reports — usually spare summaries but sometimes detailed narratives — shed light on some elements of the war that have been largely hidden from the public eye:

material comes to light as Congress and the public grow increasingly skeptical of the deepening involvement in Afghanistan and its chances for success as next year’s deadline to begin withdrawing troops looms. The archive is a vivid reminder that the Afghan conflict until recently was a second-class war, with money, troops and attention lavished on Iraq while soldiers and Marines lamented that the Afghans they were training were not being paid. The reports — usually spare summaries but sometimes detailed narratives — shed light on some elements of the war that have been largely hidden from the public eye:

• The Taliban have used portable heat-seeking missiles against allied aircraft, a fact that has not been publicly disclosed by the military. This type of weapon helped the Afghan mujahedeen defeat the Soviet occupation in the 1980s.

• Secret commando units like Task Force 373 — a classified group of Army and Navy special operatives — work from a “capture/kill list” of about 70 top insurgent commanders. These missions, which have been stepped up under the Obama administration, claim notable successes, but have sometimes gone wrong, killing civilians and stoking Afghan resentment.

• The military employs more and more drone aircraft to survey the battlefield and strike targets in Afghanistan, although their performance is less impressive than officially portrayed. Some crash or collide, forcing American troops to undertake risky retrieval missions before the Taliban can claim  the drone’s weaponry.

the drone’s weaponry.

• The Central Intelligence Agency has expanded paramilitary operations inside Afghanistan. The units launch ambushes, order airstrikes and conduct night raids. From 2001 to 2008, the C.I.A. paid the budget of Afghanistan’s spy agency and ran it as a virtual subsidiary. MORE

NEW YORKER: Among the ninety-one thousand or so documents from the Afghan war released by WikiLeaks Sunday is an incident report dated November 22, 2009, submitted by a unit called Task Force Pegasus. It describes how a convoy was stopped on a road in southern Afghanistan at an illegal checkpoint manned by what appeared to be a hundred insurgents, “middle-age males with approx 75 x AK-47’s and 15 x PKM’s.” What could be scarier than that? Maybe what the soldiers found out next: these weren’t “insurgents” at all, at least not in the die-hard jihadi sense that the American public might understand the term. The gunmen were quite willing to let the convoy through, if the soldiers just forked over a two- or three-thousand- dollar bribe; and they were in the pay of a local warlord, Matiullah Khan, who was himself in the pay, ultimately, of the American public. According to a Times report this June (six months after the incident with Task Force Pegasus), Matiullah earns millions of dollars from NATO, supposedly to keep that road clear for convoys and help with American special-forces missions. Matiullah is also suspected of (and has denied) earning money “facilitating the movement of drugs along the highway.” That is good to know. The Obama Administration has already expressed dismay that WikiLeaks publicized the documents, but a leak informing us that our tax dollars may be being used as seed money for a protection racket associated with a narcotics-trafficking enterprise is a good leak to have. MORE

dollar bribe; and they were in the pay of a local warlord, Matiullah Khan, who was himself in the pay, ultimately, of the American public. According to a Times report this June (six months after the incident with Task Force Pegasus), Matiullah earns millions of dollars from NATO, supposedly to keep that road clear for convoys and help with American special-forces missions. Matiullah is also suspected of (and has denied) earning money “facilitating the movement of drugs along the highway.” That is good to know. The Obama Administration has already expressed dismay that WikiLeaks publicized the documents, but a leak informing us that our tax dollars may be being used as seed money for a protection racket associated with a narcotics-trafficking enterprise is a good leak to have. MORE

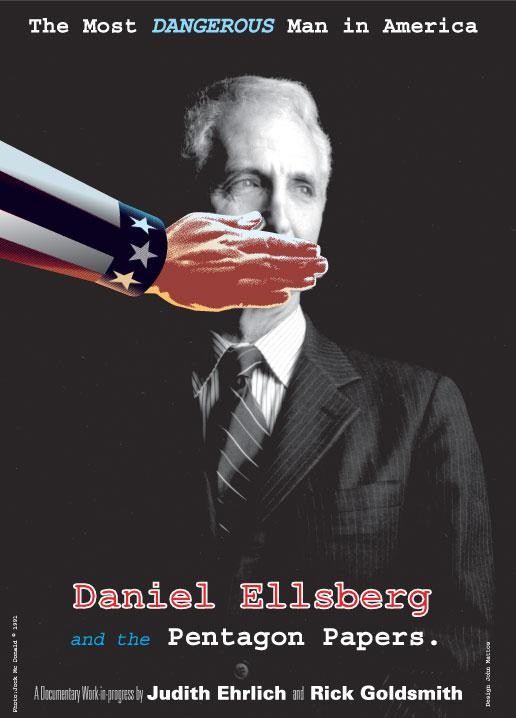

![]() FRESH AIR: The website Wikileaks publishes secret documents submitted by anonymous sources and makes them available to the public. The site, which went public in January 2007, has been compared to Daniel Ellsberg’s leaking of the Pentagon Papers in 1971. The website has leaked a variety of formerly secret documents, including “everything from investigative reports about corruption in the nation of Kenya to manuals from the

FRESH AIR: The website Wikileaks publishes secret documents submitted by anonymous sources and makes them available to the public. The site, which went public in January 2007, has been compared to Daniel Ellsberg’s leaking of the Pentagon Papers in 1971. The website has leaked a variety of formerly secret documents, including “everything from investigative reports about corruption in the nation of Kenya to manuals from the  Church of Scientology to Sarah Palin’s hacked e-mails,” explains journalist Philip Shenon. “They very famously released the so-called Climategate memos that were from a group of climate scientists that were seized upon by a group of conservatives to argue that global warming was a fraud. Shenon, an investigative reporter who contributes to The Daily Beast, joined Fresh Air‘s Dave Davies for a conversation about the website and rumors of its demise, following the release of a video showing a U.S. military massacre in Baghdad. Shenon recently wrote a series of articles about Julian Assange, the site’s founder.

Church of Scientology to Sarah Palin’s hacked e-mails,” explains journalist Philip Shenon. “They very famously released the so-called Climategate memos that were from a group of climate scientists that were seized upon by a group of conservatives to argue that global warming was a fraud. Shenon, an investigative reporter who contributes to The Daily Beast, joined Fresh Air‘s Dave Davies for a conversation about the website and rumors of its demise, following the release of a video showing a U.S. military massacre in Baghdad. Shenon recently wrote a series of articles about Julian Assange, the site’s founder.

RELATED: Last week, in a series of three articles totalling some thirteen thousand words, the paper explored the immense national-security industry created since 9/11—a bureaucratic behemoth, substantially privatized but awash in public money, that “has become so large, so unwieldy, and so secretive” that it “amounts to an alternative geography of the United States, a Top Secret America hidden from public view and lacking in thorough oversight.” […] Beyond the numbing numbers, the Post describes a vast archipelago of gleaming new office parks, concentrated in the Washington suburbs but also scattered throughout the country, protected by high fences and armed security guards, bland-looking but inaccessible, and filled with command centers, internal television networks, video walls, armored S.U.V.s, and inner sanctums called SCIFs, short for “sensitive compartmented information facilities.” How much of this—“the bling of national security,” the Post calls it—is necessary or even useful may be doubted, but it is  undeniably expensive. Much of it is there because the taxpayer cash to buy it is there—an unending, ever-growing, BP-worthy fiscal blowout that, beginning just after 9/11 and continuing to this day, flooded the agencies with “more money than they were capable of responsibly spending,” the Post writes. “They’ve got the penis envy thing going,” a contractor whose business specializes in building SCIFs says. “You can’t be a big boy unless you’re a three-letter agency and you have a big SCIF.” Moreover, fully a quarter-million holders of top-secret security clearances are employees not of the government but of private, profit-making businesses. Government agencies serve as a hiring hall for contractor corporations offering perks and salaries the agencies can’t match, leaving them to rely on recent graduates whose familiarity with the countries they analyze, including their languages, is minimal. The concern this raises—a concern that Robert M. Gates, the Secretary of Defense, and Leon Panetta, the head of the C.I.A., told the paper they share—is “whether the federal workforce includes too many people obligated to shareholders rather than the public interest—and whether the government is still in control of its most sensitive activities.” MORE

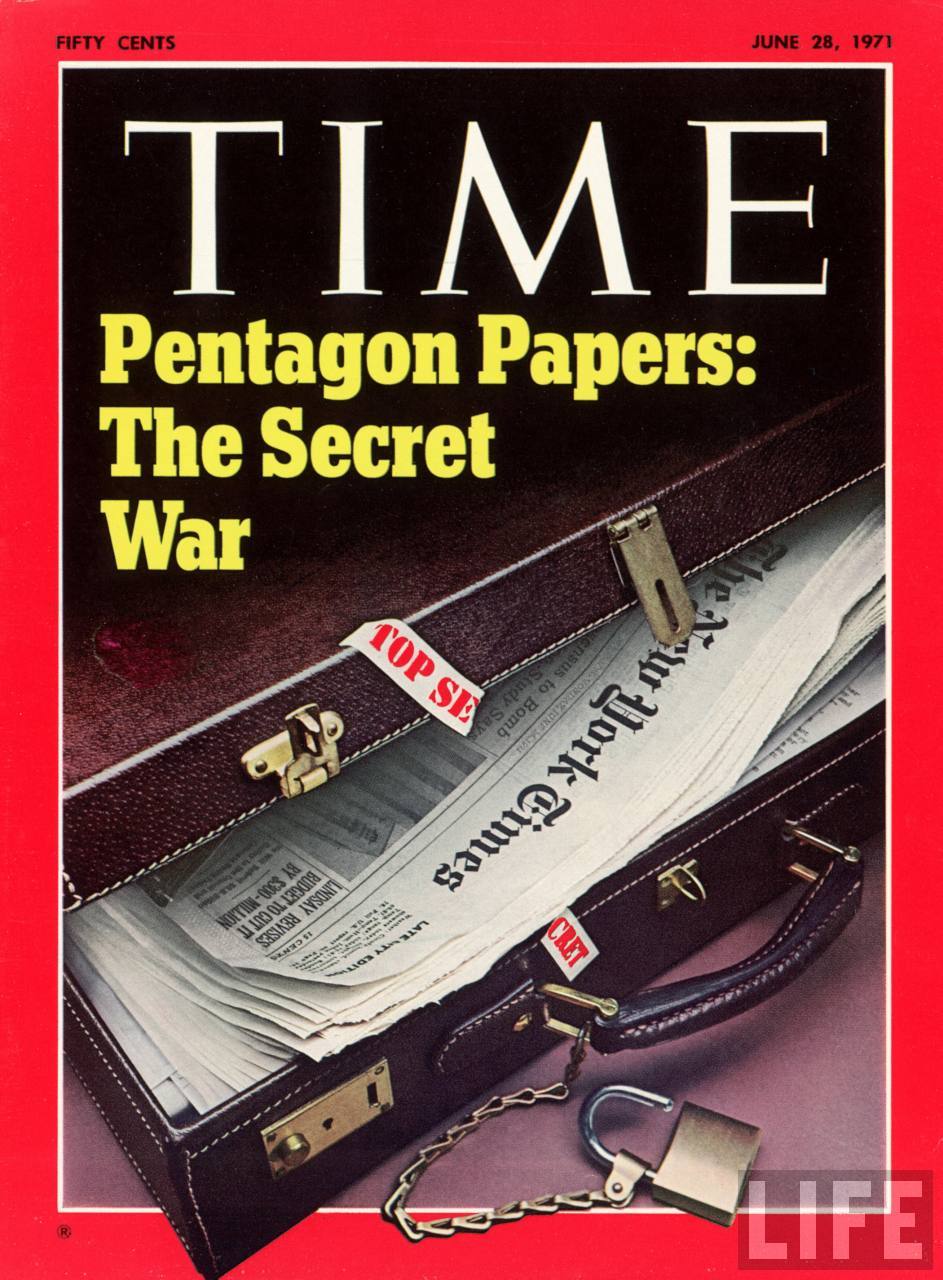

undeniably expensive. Much of it is there because the taxpayer cash to buy it is there—an unending, ever-growing, BP-worthy fiscal blowout that, beginning just after 9/11 and continuing to this day, flooded the agencies with “more money than they were capable of responsibly spending,” the Post writes. “They’ve got the penis envy thing going,” a contractor whose business specializes in building SCIFs says. “You can’t be a big boy unless you’re a three-letter agency and you have a big SCIF.” Moreover, fully a quarter-million holders of top-secret security clearances are employees not of the government but of private, profit-making businesses. Government agencies serve as a hiring hall for contractor corporations offering perks and salaries the agencies can’t match, leaving them to rely on recent graduates whose familiarity with the countries they analyze, including their languages, is minimal. The concern this raises—a concern that Robert M. Gates, the Secretary of Defense, and Leon Panetta, the head of the C.I.A., told the paper they share—is “whether the federal workforce includes too many people obligated to shareholders rather than the public interest—and whether the government is still in control of its most sensitive activities.” MORE RELATED: The Pentagon Papers, officially titled United States–Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense, was a top-secret United States Department of Defense history of the United States‘ political-military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967. Commissioned by United States Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara in 1967, the study was completed in 1968. The papers were first brought to the attention of the public on the front page of the New York Times in 1971.[1] A 1996 article in the New York Times said that the Pentagon Papers “demonstrated, among other things, that the Johnson Administration had systematically lied, not only to the public but also to Congress, about a subject of transcendent national interest and significance”. The study was classified as top secret and was not intended for publication. Contributor Daniel Ellsberg, however, turned over most of the Pentagon Papers to New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan, with Ellsberg’s friend Anthony Russo assisting in their copying. The Times began publishing excerpts in a series of articles on June 13, 1971.[3] Street protests, political controversy and lawsuits followed. MORE

RELATED: The Pentagon Papers, officially titled United States–Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense, was a top-secret United States Department of Defense history of the United States‘ political-military involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967. Commissioned by United States Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara in 1967, the study was completed in 1968. The papers were first brought to the attention of the public on the front page of the New York Times in 1971.[1] A 1996 article in the New York Times said that the Pentagon Papers “demonstrated, among other things, that the Johnson Administration had systematically lied, not only to the public but also to Congress, about a subject of transcendent national interest and significance”. The study was classified as top secret and was not intended for publication. Contributor Daniel Ellsberg, however, turned over most of the Pentagon Papers to New York Times reporter Neil Sheehan, with Ellsberg’s friend Anthony Russo assisting in their copying. The Times began publishing excerpts in a series of articles on June 13, 1971.[3] Street protests, political controversy and lawsuits followed. MORE