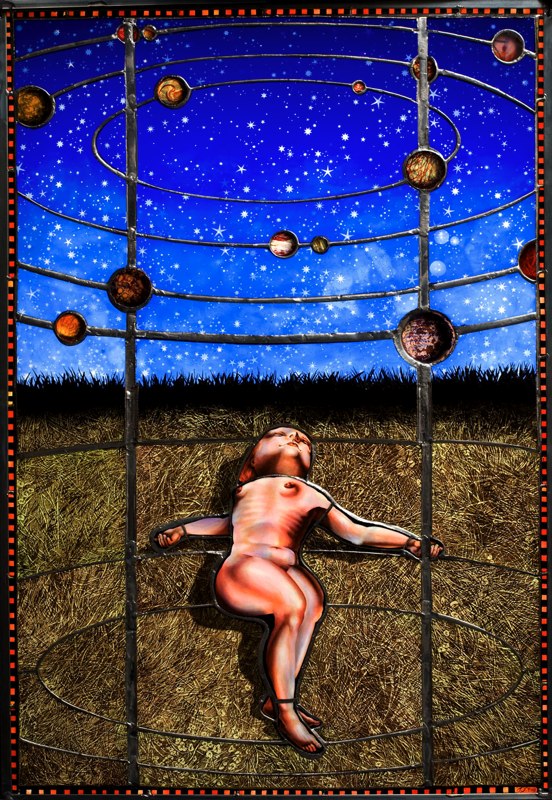

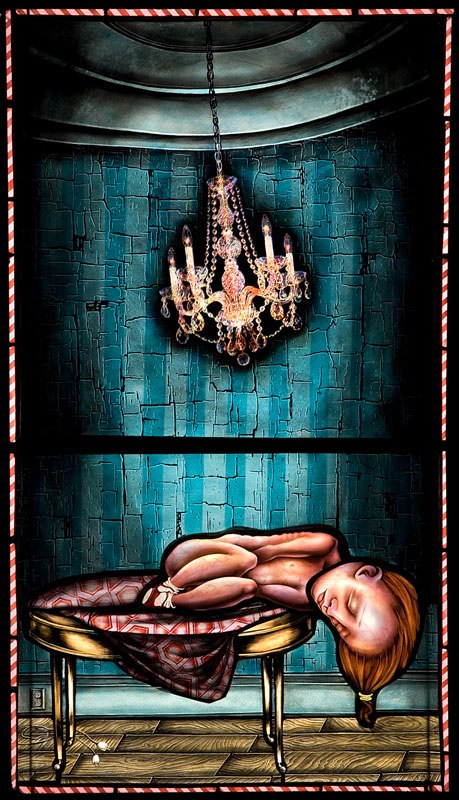

[“You Are Here” by JUDITH SCHAECHTER]

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA Judith Schaechter is a world renowned stained glass artist who has resided here in Philadelphia since graduating from Rhode Island School Of Design in 1983. (It was there that she met acclaimed novelist Rick Moody, then a student at nearby Brown, and the two attempted to be boyfriend/girlfriend, but eventually settled into a friendship that has lasted all these years.) Her work retrieves the lost art of stained glass-making from the dustbin of the Middle Ages — where it largely served as a decorative form pressed into the service of replicating religious iconography — and pushes it through a post-punk filter shot through with sex and death and romance and violence to create something deeply personal, inscrutably modern, and ineffably beautiful. If David Lynch was medieval monk prone to ecstatic visions, presumably after days of fasting and self-flagellation (which were the psychedelic drugs of their day) — well, it would all look a lot like Schaechter’s art. Small wonder her works sell for upwards of $80,000 in the New York gallery scene, and have found a permanent home in The Metropolitan Museum Of Art in New York, the Smithsonian, the Philadelphia Art Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Judith Schaechter is a world renowned stained glass artist who has resided here in Philadelphia since graduating from Rhode Island School Of Design in 1983. (It was there that she met acclaimed novelist Rick Moody, then a student at nearby Brown, and the two attempted to be boyfriend/girlfriend, but eventually settled into a friendship that has lasted all these years.) Her work retrieves the lost art of stained glass-making from the dustbin of the Middle Ages — where it largely served as a decorative form pressed into the service of replicating religious iconography — and pushes it through a post-punk filter shot through with sex and death and romance and violence to create something deeply personal, inscrutably modern, and ineffably beautiful. If David Lynch was medieval monk prone to ecstatic visions, presumably after days of fasting and self-flagellation (which were the psychedelic drugs of their day) — well, it would all look a lot like Schaechter’s art. Small wonder her works sell for upwards of $80,000 in the New York gallery scene, and have found a permanent home in The Metropolitan Museum Of Art in New York, the Smithsonian, the Philadelphia Art Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

If the acknowldgement of your peers is a measure of your cred, Schaechter tips the scales. She has received Guggenheim Fellowship, two National  Endowment for the Arts Fellowships in Crafts, The Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, The Joan Mitchell Award, two Pennsylvania Council on the Arts awards, The Pew Fellowship in the Arts and a Leeway Foundation grant. She has taught at The Pilchuck Glass School in Seattle, The Penland School of Crafts, the Toyama Institute of Glass in Japan, The Pennsylvania Academy, the New York Academy of Art, The University of the Arts. and her old alma mater Rhode Island School of Design. Schaechter was included in the 2002 Whitney Biennial and she was a 2008 USA Artists Rockefeller Fellow.

Endowment for the Arts Fellowships in Crafts, The Louis Comfort Tiffany Award, The Joan Mitchell Award, two Pennsylvania Council on the Arts awards, The Pew Fellowship in the Arts and a Leeway Foundation grant. She has taught at The Pilchuck Glass School in Seattle, The Penland School of Crafts, the Toyama Institute of Glass in Japan, The Pennsylvania Academy, the New York Academy of Art, The University of the Arts. and her old alma mater Rhode Island School of Design. Schaechter was included in the 2002 Whitney Biennial and she was a 2008 USA Artists Rockefeller Fellow.

On the heels of a recent exhibition at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Manhattan, Phawker got Schaechter on the horn for a career retrospective. We discuss the ironies of an atheist working in a religious art form, the mind-bending valuations of the current art market, the dangers of working with lead and what it’s like to have singer of the Stone Temple Pilots as your most famous patron. The short answer is that you get to hang out back stage with the Meat Puppets.

PHAWKER: Let’s start at the beginning, how did you decide to do what you do?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Ah, well I went to art school — because I was a nerd, and that’s what nerds do. I had taken a lot of painting classes. But I remember that when I was really young my parents used to take me to this art center, and the only materials they had there were for making collage — and I loved it because I really wanted all those materials for my dollhouse. So I put them all together in a collage and took it home and ripped it apart and put it all in my dollhouse. But back to the future, I didn’t get into stained glass until after college, where I was a painting major. At school the painting studio was right next to the glass studio and I used to wonder in there. Almost everyone who walks into a glass studio falls in love with the glass-blowing process because it’s very balletic and theatrical and quite seductive. But for whatever reason I was really turned on by the stained glass glass and I tried very hard to get into but it was already full. My intention was just to make a doo-dad for my window, but almost immediately, weeks at the most, I knew this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. In hindsight I have to ask myself: Is there something in me that makes me predisposed to liking this medium so much? And all can think of is that I was very fond of Lite Brite, I mean really fond of Lite Brite. I remember they used to have these patterns that you could follow to create pictures, but I would always make my own. And I also always liked those bake-in-the-oven suncatchers and stuff.

PHAWKER: It’s a very rare form, correct? Not many people are working in this medium these days, correct?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: That’s a nice way of spinning it. Another way would be to say it’s a dead medium. It came and it went, basically. There are people who do stained glass and I know them all. It’s a very small field, it’s not taught in art school. The industry, if you want to call it that, survives on artisans and family studios that have been passed down from generation to generation. It is certainly not taught as an artistic discipline with any degree of seriousness.

PHAWKER: Can you talk a little about the history of stained glass, how far does it stretch back? And was it entirely connected to the church?

PHAWKER: Can you talk a little about the history of stained glass, how far does it stretch back? And was it entirely connected to the church?

JUDITH SHAECHTER: It’s a very finite history. The very first scrap of stained glass is from Stainbourg or Elksbourg or one of those Bourgs, in Germany. It is fully recognizable as having everything we associate with stained glass today, in other words it’s colored glass that’s been cut up, assembled with lead, and painted with a mixture of frit, which is a mixture of crushed glass and iron filings and all that crap. It’s a head of Jesus. What they surmise is that the form rose from using organic things, like colored glass that was in plaster frames that had rotted and that it was inspired by looking at cloisonné, which gave them the idea of assembling the glass with lead came, which are the bars of lead. Anyway, that first scrap of stained glass dates back to 1100.

PHAWKER: When did it get to the point where there was a big demand for stained glass?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well, there was a big demand and lots of studios and guilds producing up until the Protestant Reformation, which killed it dead. In fact, in England Cromwell ordered all the stained glass windows to be smashed, which is why there is a lot of very bizarre stained glass windows in England, because eventually people tried to re-assemble them the best they could. They are kind of cool in their own right, these jumbly, mish-mashes of stuff. Up until The Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation, it was going strong and that was the end of it. It has survived as sort of heraldic emblems for rich people, and it’s sort of hobbled along until the arts and crafts movement and the Gothic Revival — people like Tiffany, which was a shot in the arm. But I don’t think it ever really recovered. The golden era was right around 1200 A.D.

PHAWKER: You are talking about Tiffany of Tiffany Lamp fame? Was Tiffany a man or a woman?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: He was a dude!

PHAWKER: Tough name to rep on the playground.

JUDITH SHAECHTER: People always assume Tiffany is a woman because his lamps are so pretty!

PHAWKER: So Tiffany Lamps are sort of a strange second cousin of stained glass?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Yes. There is a whole sort of war between American and European approaches. Tiffany was an American and his take on stained glass was a real paradigm shift. He had a factory that blew him glass that was not so much transparent but translucent, that weird milky look that a Tiffany window has.

PHAWKER: So when are we talking about here, when was Tiffany on the scene?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Dawn of the Industrial Revolution, or the early 1900s.

PHAWKER: To the best of your knowledge are there any other people like you working in the form that show in fine arts galleries and sell their work  for significant sums of money?

for significant sums of money?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: No, there are not. It might sound like egomania, but there are not. Like I said, the field is very small. It runs the gamut of people that are working in architecture, which I am not, and there are people that are working on commissions, which I am not.

PHAWKER: Just to sketch out some of your accomplishments, some of your pieces have been purchased by major museums around the world, correct?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Correctamundo. The Metropolitan Museum in New York has one. The Philadelphia Museum of Art has two. There is one in the collection of the Victorian Albert in London, one in the de Young Museum in San Francisco, The Carnegie in Pittsburgh — they have the best one, I think. And then there’s some smaller museums, like the Speed Museum in Kentucky.

PHAWKER: Speed? Is that someone’s name? It’s not a museum about speed is it?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: They show nothing but fast women and meth! Wouldn’t that be cool?

PHAWKER: Yeah, I’d go. So, let’s talk about technique. You are innovating the form by using the age-old techniques of stained glass work but you are combining them in new ways, correct?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Yes, what makes me distinct is that I use every known technique to some insane degree and that’s not really done. It’s unheard of that someone would sandblast and paint and etch every single piece of the whole window. I certainly didn’t invent these techniques but I am taking them places they have never been before.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about influences, specifically the faces in your work are so distinct and somewhat familiar…

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: The faces are not really influenced by anything other than the process of drawing and my own imagination. Having said that, with the Internet, I must look at a thousand images a day, there’s like 10,000 tumblr sites I compulsively check: art, advertising, comics, old book illustrations, anything visual inspires me, so it’s not just a specific period of art.

PHAWKER: Since what you do is so unique, was it difficult to convince gallery owners to take you seriously?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well, my greatest gift has been to be totally convinced of my fabulousness and that anyone who works with me was so lucky. [laughs] That sounds much more arrogant when I say it out loud, but it’s true. I wish I could extend that attitude to my love life. But I’ve just always had a lot of confidence about my work and it never occurred to me that people might not like it or want to show it in their gallery. Having said that, not everybody likes it, but my attitude is how can I make you love me more? You’ll feel so much better when you do. But there is a lot of politics involved in the art world, there is a lot of corruption and it’s not a meritocracy. At the same time, it does boil down to: if you make something that someone wants, that’s gonna sell.

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well, my greatest gift has been to be totally convinced of my fabulousness and that anyone who works with me was so lucky. [laughs] That sounds much more arrogant when I say it out loud, but it’s true. I wish I could extend that attitude to my love life. But I’ve just always had a lot of confidence about my work and it never occurred to me that people might not like it or want to show it in their gallery. Having said that, not everybody likes it, but my attitude is how can I make you love me more? You’ll feel so much better when you do. But there is a lot of politics involved in the art world, there is a lot of corruption and it’s not a meritocracy. At the same time, it does boil down to: if you make something that someone wants, that’s gonna sell.

PHAWKER: Can you talk a little bit about how you found your place in the art world’

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: I started out at Nexus, the co-op and I loved it. It was a great place to start because you really learn a lot. Next I was picked up by Snyderman Gallery after I had an exhibition at Fleisher Art Memorial in one of their challenge exhibitions, and he established me much firmer in the area in between craft and art. I felt like we were a partnership. Then I went with Claire’s, who is strictly a fine arts gallery. I think stained glass is a very weird medium because it is sort of associated with crafts, but because it’s not utilitarian, like, you can’t drink water out of it and stuff like that, it functions more like a painting, so in a way it makes sense to exhibit it like a painting as well. I have had people say to me that they won’t show my work because it’s glass and they simply don’t do that, so, it hasn’t been the case that I say I think it’s great and everybody just agrees [laughs]. Maybe close, but not quite.

PHAWKER: So you recently exhibited your work in New York?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Yes, at the Claire Oliver Gallery.

PHAWKER: I saw the exhibit, and it was incredibly awesome. If this is not too personal, I would like to talk about how much your work sells for. I’ve heard talk that some of them can go for $30,000 a piece. Is that about right?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: I think the price ranges from about $20,000 to $80,000.

PHAWKER: So how does this usually work? Do you do a new exhibition every two or three years roughly?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Yeah. I do a new exhibition about every two years. There are other exhibitions but they borrow back older ones.

PHAWKER: And does pretty much all of your work sell?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well, up until the economic crash I was doing really well. It’s a little harder now, but also I haven’t given Claire’s any new work in a really long time. I’m going to try to be careful how I phrase this. [Laughs] I’m sorry, I love being totally honest, and I’m not the only person who could be upset about how this comes out. Basically, there is definitely a downturn with the economic disaster, and I’m still sort of looking to see how that’s going to pan out. I didn’t give Claire’s any work for a year because I was working on a show, and she didn’t ask for anything and it was just easier; she wanted to have it all for the exhibition, and I still had enough money in savings that I could afford to do that, so, we’ll see!

PHAWKER: Do you have any famous clients we should know about?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Not really [laughs]. I sold one to the lead singer of Stone Temple Pilots, but that was a long time ago.

PHAWKER: Scott Weiland?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: [laughs] Yeah.

PHAWKER: How did that come about?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: I had a show at an art gallery in L.A. in 1990, in fact I just had another one last year, but I showed stained glass there in 1990, and it was really interesting. Nothing really happened at the show. I think I sold maybe one piece, but it led to very strange long term fallout with the manager for Stone Temple Pilots who saw the show. Apparently when they came through Philly, Scott Weiland wanted to buy his wife to be, his now ex-wife, a wedding gift and he bought her one of my windows and there you go. I don’t know what ever happened to it.

PHAWKER: Did he come to your house?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: He came to my studio with the drummer. And they signed a copy of their record Purple, the one that has “Vasoline” on it. The drummer wrote “I love art; beer makes me fart.” [laughs] What I was most excited about was that the Meat Puppets were opening for them here in Philly so I got to hang out with the Meat Puppets backstage!

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: He came to my studio with the drummer. And they signed a copy of their record Purple, the one that has “Vasoline” on it. The drummer wrote “I love art; beer makes me fart.” [laughs] What I was most excited about was that the Meat Puppets were opening for them here in Philly so I got to hang out with the Meat Puppets backstage!

PHAWKER: Up On The Sun, baby.

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: [laughs] There you go. But this was years ago, like 1993 or something.

PHAWKER: Can we talk for a second about the valuation of art? Did I hear recently that there was a Picasso that sold for like $120 million dollars? I just can’t fathom that.

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: I don’t follow the auctions, but I’m guessing the cost of materials is substantially lower. [laughs]

PHAWKER: Yes there was quite a profit margin on that.

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well no profits for him, he’s dead. [laughs] but I think with the valuation of art, the ideas of branding and mystique get really obnoxious because it’s a very, very high stakes game. It’s not like the economy of records and books where a lot of people have to like you, and they all contribute a little bit of money; this is more like you just need one person of means. So it’s a really different game economically. Part of me wants to defend it, since you can’t put a value on something like a Picasso because it’s an experience presumably to the person who thought it was worth that much. They weren’t buying it as an investment, but because they were united with the divine when confronting it, you know? That’s supposedly what the mystique is here, that you’re really getting something, and that it’s not the emperor’s new clothes. But the fact is these prices get inflated because of hype.

PHAWKER: Well, I guess my question is whether it’s really worth that much. Let’s just stick with $120 million for a second as an example. It’s worth $120 million to that guy who paid that much money, but technically it’s only worth that much money if there’s someone else out there also willing to buy it from him for $120 million.

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well there’s a whole lot of weird things going on in the art world. I’ve been asked by the Glass Art’s Society to please donate  a piece to their auction, which sounds good as a tax write-off, but the only things I’m allowed to write off are the materials. The cost of materials alone, nothing else; not my time, and if someone buys it for $20,000, and then they donate it to another auction, they get to write off a $20,000 art work, because an unsold art work has no value whatsoever. So the very act of this guy having made this sale for a lot of money sort of confirms its worth. So there’s a horrible downside if you’re a struggling artist. It’s sad, and it’s also the reason why a lot of more established artists don’t want to donate to charity auctions.

a piece to their auction, which sounds good as a tax write-off, but the only things I’m allowed to write off are the materials. The cost of materials alone, nothing else; not my time, and if someone buys it for $20,000, and then they donate it to another auction, they get to write off a $20,000 art work, because an unsold art work has no value whatsoever. So the very act of this guy having made this sale for a lot of money sort of confirms its worth. So there’s a horrible downside if you’re a struggling artist. It’s sad, and it’s also the reason why a lot of more established artists don’t want to donate to charity auctions.

PHAWKER: I see. Let’s talk about some of the hazards of your work. You work with lead, which is obviously very toxic — most stained glass uses a lead framework to puzzle together the pieces of colored glass. Are you constantly monitoring your lead levels and drinking milk to stave off lead poisoning?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: [laughs] I do drink milk, and I hate it. I do work with lead, but the material comes in many forms, and the way you get lead poisoning is by eating it, or by inhaling dust. I work with lead in the form of smoke, because I don’t use the lead bars; I assemble it with copper foil and a soldering gun, which gives off the lead smoke, but the fact is if lead gets on my fingers and I wash my hands I’m fine. I do have my lead level tested regularly, and it is below normal. Ingesting lead is very dangerous, so you want to be very careful, but I think that there’s a level of panic in the public that’s a little overstated. You should be very careful if you’re pregnant, and you should be careful that your children aren’t eating paint chips. It’s a little known fact that lead paint chips tastes somewhat sweet. That’s why kids eat them, they are sort of like candy.

PHAWKER: Really?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Yeah; I have not eaten it, I have only heard. The Romans used lead to sweeten their wine. But the forms of lead I’m using aren’t particularly dangerous. There’s no danger in touching it as long as you don’t rub your hands all over it and then lick them in the manner of someone who just had a bucket of chicken.

PHAWKER: But just even that little bit of exposure is harmful, if you rubbed your hands over lead and licked it?

PHAWKER: But just even that little bit of exposure is harmful, if you rubbed your hands over lead and licked it?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well the thing about lead poisoning is that it’s cumulative. So if you’ve had no prior exposure to lead you can probably rub your whole body over it and lick yourself like a cat for a good long time and you’ve got a lot of leeway, but if you ate a lot of paint chips when you were a kid you can’t get away with that [laughs]. It just depends on what level of exposure you’ve had in the past.

PHAWKER: So it stays in the body?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: It does, and you know what, I think the biggest danger for lead is actually car batteries and emissions. So people are always trying to ban materials that some stained glass artist’s work with, which I feel is sort of a personal issue for me. It is completely misunderstood and there’s a lot of panic about it, where there really doesn’t need to be. We could better direct it to the actual polluters. Like, people who remove stained glass windows from churches create a lot of dust, and that dust has lead in it, and that’s extremely dangerous.

PHAWKER: So if you do get lead poisoning, then what do you do?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: You do something called Chelation therapy which is kind of like chemotherapy, and it binds the lead to your shit and then you crap it out, but it’s supposedly torture.

PHAWKER: Two more questions. Since we were talking about famous people, I heard you were close friends with Rick Moody?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Right he went to Brown and I went to RISD.

PHAWKER: Oh, so you guys didn’t go to school together you just knew each other from Rhode Island at the time?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Right, yeah we were really good friends, and actually we were sort of boyfriend and girlfriend; it was more like we tragically attempted to connect and just tortured each other [laughs]. I’ve known him for a really long time and now he’s a dear friend.

PHAWKER: That’s great. Lastly, can we talk about the irony of you being a professed atheist working in a form that is essentially a religious form, or at least was before you got a hold of it?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: I was raised an atheist. I’m very comfortable saying I’m not an atheist and saying I’m an atheist at the same time. I would not say I’m an atheist all the way, but I also wouldn’t say I’m an agnostic. I’m just going to be really infuriating right now. I am so out on the question of spirituality and religion. I think the normal way this is expressed is ‘I’m an atheist but really spiritual,’ right? I didn’t want to go there, but it’s sort of like that. My father was Jewish when he was young and my mother was Episcopal. And my mother, by the way, was a total Jesus freak at some point. By the time they were young adults, before they had children, they were over it and they were atheists. They were like Commie, Jewish atheists.

PHAWKER: Are you a red diaper baby?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Yes. Well, they were less than political, but if they had to be political that’s what they would have been. They were really  liberal, so I don’t really have a database for any sort of religion. I couldn’t just say tomorrow “Wow! Spirituality is really beautiful; I’m going to go join the Moonies!” I’m like cult-proof, so that’s why I hesitate to say spiritual. I’m not superstitious even remotely, but I’ve had experiences being inspired as an artist that were what I would call holy, and quite wonderful. I would love to go to church, actually. I have no axe to grind against religion whatsoever, but to answer your question, I think it was a blessing to not have a background of going to church, because I never thought for a minute that stained glass had to be one thing or another since I was never indoctrinated to any of that. I think in some ways what’s really strange is that completely independent of religion I came to some of the same conclusions about the use of stained glass to depict moments of transcendence, which is what I think the saints in those stained glass windows are supposed to be doing. So I think there is a great coinciding between my work and religious work. It’s maybe a little arrogant to say I came to the conclusion independently, but I did.

liberal, so I don’t really have a database for any sort of religion. I couldn’t just say tomorrow “Wow! Spirituality is really beautiful; I’m going to go join the Moonies!” I’m like cult-proof, so that’s why I hesitate to say spiritual. I’m not superstitious even remotely, but I’ve had experiences being inspired as an artist that were what I would call holy, and quite wonderful. I would love to go to church, actually. I have no axe to grind against religion whatsoever, but to answer your question, I think it was a blessing to not have a background of going to church, because I never thought for a minute that stained glass had to be one thing or another since I was never indoctrinated to any of that. I think in some ways what’s really strange is that completely independent of religion I came to some of the same conclusions about the use of stained glass to depict moments of transcendence, which is what I think the saints in those stained glass windows are supposed to be doing. So I think there is a great coinciding between my work and religious work. It’s maybe a little arrogant to say I came to the conclusion independently, but I did.

PHAWKER: So you’re saying almost accidentally you arrived at the same conclusions, but just took different routes.

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Exactly. When you work with stained glass, really the meaning isn’t the actual stuff, it’s the light coming through it, how you modulate it, and how that affects people looking at it. Like, when you look at clay before an artist touches clay, it looks like something you’d find in the bottom of your toilet before you flush, [laughs] so whatever the artist does is going to be an improvement. When you look at the glass that I’m working with, pretty much everything the artist does is going to make it worse, because it’s already beautiful.

Abbott Suger [the philosopher and historian who’s name is synonymous with Gothic architecture] said that “stained glass is enlightenment embodied.” I interpret that to mean it’s not a metaphor, but a literal experience of enlightenment because when you stand in front of it, especially if it’s lit by sunlight, you can shut your eyes and feel the warmth. Unlike a painting, you actually feel it inside your body. So it’s a very physical thing, kind of like music, actually, because music you feel inside your body with your eyes shut. It has a resonance that is much deeper then the experience of reflected light that paintings and sculpture require, so because it transmits light, which actually penetrates your skin and goes into your body, it can be perceived that way. It’s very, very powerful. I think it lends itself to subject matter that depicts transformative moments and things of that nature, so in other words it’s not that crazy that I would come to the same conclusion as the church.

PHAWKER: Nice. Is there anything else you would like to add?

JUDITH SCHAECHTER: Well, I hope I didn’t sound too snotty! [laughs]

[Portrait of Judith Schaechter by ADAM WALLACAVAGE]