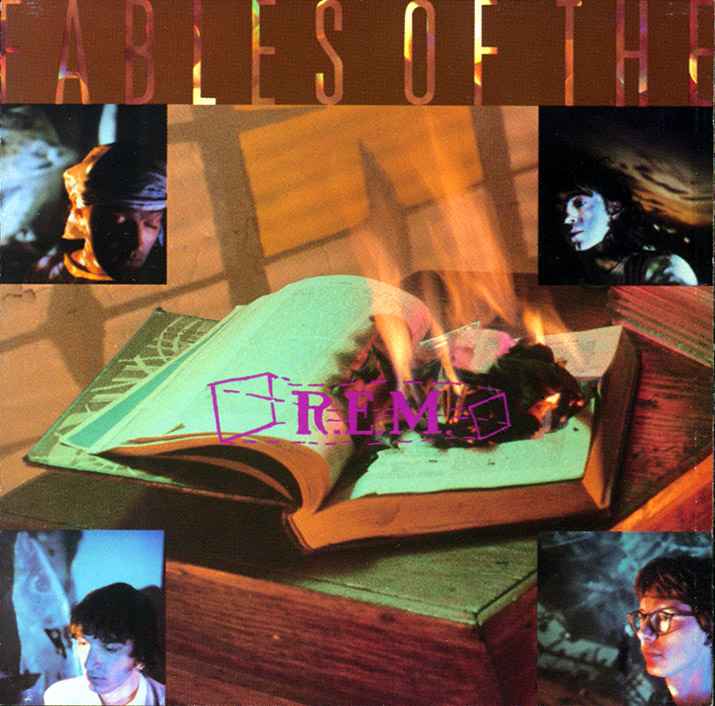

POP MATTERS: Recording outside of the American South for the first time, R.E.M. imbued Fables of the Reconstruction with the spirit of its place of origin. What largely set early alt-rock bands like R.E.M. apart from the punk and post-punk movements with which they coexisted was how they rebelled against the present by signifying sounds and iconography from the pre-punk past, albeit in a recontexualized, postmodern fashion. In R.E.M.’s case, this tendency had been manifested in its early work by Peter Buck’s Byrdsian guitar jangle and in the band’s vague rural mystique, one that was provincial without being cliché. Fables of the Reconstruction delved further into the past than the band had ever journeyed before, conjuring up the spirit of a mythical South of nebulous antiquity as envisioned by the group—imagine a post-American Civil War South as if it had access to records made a century later—through a combination of potent musical signifiers (banjos and slower country music-inspired tempos matched up with Buck’s ever-present jangle) and Michael Stipe’s fascination with the storytelling tradition of the region. From its connotation-heavy title to its timbres, Fables of the Reconstruction becomes a record about the pervading sense of place, one where listeners can practically hear the Southern Crescent railroad line chug along, feel the warm Georgia air, and see endless rolling fields of native agriculture as the band plays.

Listeners can bear witness on this album to a major step in Stipe’s development as a lyricist. While still rooted in the oblique  mumbles of past compositions, the songs on Fables of the Reconstruction constituted Stipe’s admitted first attempts at narrative writing. Stipe told NME in 1988 that the album was “pretty much my version of the storytelling tradition. Me playing the Brothers Grimm or Aesop.” Fables is loaded with all sorts of local eccentric characters that give the South its unique character, including dog kidnappers (“Old Man Kensey”), used car salesmen (the banjo-laden country-fied closer “Wendell Gee”), train conductors (“Driver 8”), and crazy old coots who divided their homes in two (“Life and How to Live It”). Stipe proves his mettle as a lyricist by being able to match his narrative fascinations with strong descriptive snippets of the everyday mundane, making lines like “I saw a treehouse on the outskirts of the farm / The power lines have floaters so the airplanes won’t get snagged” from “Driver 8” function as pure poetry.

mumbles of past compositions, the songs on Fables of the Reconstruction constituted Stipe’s admitted first attempts at narrative writing. Stipe told NME in 1988 that the album was “pretty much my version of the storytelling tradition. Me playing the Brothers Grimm or Aesop.” Fables is loaded with all sorts of local eccentric characters that give the South its unique character, including dog kidnappers (“Old Man Kensey”), used car salesmen (the banjo-laden country-fied closer “Wendell Gee”), train conductors (“Driver 8”), and crazy old coots who divided their homes in two (“Life and How to Live It”). Stipe proves his mettle as a lyricist by being able to match his narrative fascinations with strong descriptive snippets of the everyday mundane, making lines like “I saw a treehouse on the outskirts of the farm / The power lines have floaters so the airplanes won’t get snagged” from “Driver 8” function as pure poetry.

Although this head-first immersion into Southern iconography benefited Stipe’s lyricism, it trapped the rest of the band in a musical cul de sac. In particular, Peter Buck is stuck on one of two settings for much of the album: languid midtempo folksy jangle or driving moderately fast jangle. Buck’s playing on Fables is adept and never boring, but the guitarist’s constant reliance on his trademark technique threatens to devolve into self-parody by album’s end. Loaded with one janglefest after another, Fables becomes R.E.M.-squared, a record where the group’s stylistic tics are amplified into an overwhelming uniformity that really does become too much of a previously good thing. Nothing demonstrates this problem better than the remarkable similarity between the verses of “Maps and Legends” and “Kohoutek”. Trapped by its provincial vision and its cloistered rejection of modernity, the only exits the band provides are moody Anglophilia (the Gang of Four-inspired “Feeling Gravitys Pull”) and jokey irreverence (the weak white funk single “Cant Get There from Here”, which grows more embarrassing with each passing year), both of which exist at jarring right angles to the album’s established tone. MORE

PREVIOUSLY: Riddle Me This