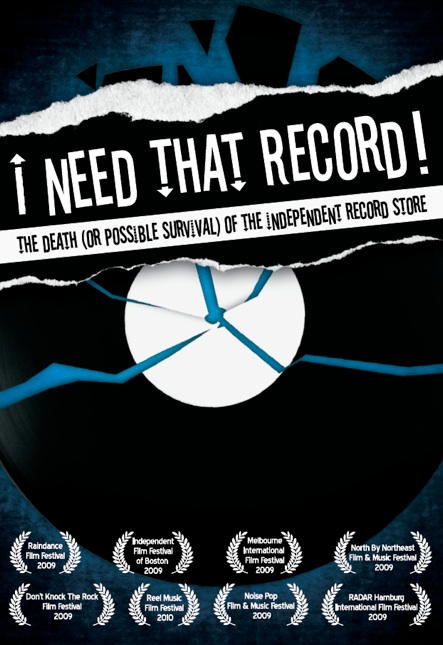

BY DAVID M. SNYDER Subtitling his documentary The Death (or Possible Survival) of the Independent Record Store, I Need That Record! director Brendan Toller imagines he’s telling some great conspiracy tale in his pursuit of an explanation for why more than 3,000 independent record stores have closed in the last decade. But in reality he presents a partial picture, picking and choosing the facts that will heighten his thesis. The movie itself is composed of an intertwining of interviews with a select number of independent record store proprietors from a couple of regions of the country, with a focus on the demise of two from his youth in Connecticut (Record Express and Trash American Style), talking head interviews with sympathetic musicians (Glenn Branca, Lenny Kaye, Mike Watt, Thurston Moore, and others), and equally sympathetic writers like Noam Chomksy and the always self-aggrandizing Legs McNeil.

BY DAVID M. SNYDER Subtitling his documentary The Death (or Possible Survival) of the Independent Record Store, I Need That Record! director Brendan Toller imagines he’s telling some great conspiracy tale in his pursuit of an explanation for why more than 3,000 independent record stores have closed in the last decade. But in reality he presents a partial picture, picking and choosing the facts that will heighten his thesis. The movie itself is composed of an intertwining of interviews with a select number of independent record store proprietors from a couple of regions of the country, with a focus on the demise of two from his youth in Connecticut (Record Express and Trash American Style), talking head interviews with sympathetic musicians (Glenn Branca, Lenny Kaye, Mike Watt, Thurston Moore, and others), and equally sympathetic writers like Noam Chomksy and the always self-aggrandizing Legs McNeil.

But what Toller never seems to acknowledge is that the national and major regional chains have been even hit even harder by the rise of the Internet than the independent record stores. There is pretty much only one major chain left in the U.S.: Trans World Entertainment, aka F.Y.E. (A markedly partial list of the chains that have left this world: Camelot, Coconuts, Licorice Pizza, Listening Booth, Musicland, National Record Mart, Peaches, Record Bar, Record Town, Record World, Sam Goodys, Strawberries, Tower, Turtle’s, Vibes Music, Wall to Wall & Wherehouse.)

In the pursuit of praising the mom and pop shops at the expense of the corporate chains, Toller throws out a few red herrings, most notably that the chains were impersonal and staffed by a bunch of know-nothings. This may be true in stores where music retailing is only a small portion of their overall business, such as Wal-Mart, but back in the heyday of the chains I knew many staffers who were the equal in knowledge, interest and passion about music as you could find in any indie shop. (Disclosure: I spent a year on staff at Sam Goodys). True, the chains did limit the scope of their stock, especially in the post-‘76 explosion of the new indie record companies. Toller and co. seem genuinely shocked (SHOCKED!) to learn that the nature of capitalism is to create vast, impregnable monopolies by any means necessary.

On the other hand Toller does astutely indentify many of the aggravating factors in the music industry’s current malaise: The devolution of music radio formats towards minimal playlists and consolidation of station ownership. The short-sighted management and big-spender extravagances of the major labels. There was a time when record sales were considered recession-proof, so major labels had few qualms about increasing prices whenever they desired, and throwing money away with seemingly little thought. The effects of Big Boxes and their loss-leader retail strategies against the little guys, not to mention the ever-increasing competition from movies and video games for consumers’ dwindling attention spans and shrinking disposable income.

The real prize here is the extra material, specifically the extended interviews with Glenn Branca, Mike Watt, Ian MacKaye, Thurston Moore, Lenny Kaye and Paterson Hood. They all start with the first records they ever bought, which leads into their evolution as music fans and their views on the business. I found these segments quite interesting because I’ve had limited interest in the music these fellows have made and thus hadn’t paid much attention to who they are outside of the context of their music. For instance Thurston Moore reveals that the first album he bought was Iron Butterfly’s In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida. Then he goes on to talk about how as a kid he couldn’t afford new releases and thus mostly scavenged what he could from the cut-out bins, a treasure trove of all the often-wonderful square pegs that didn’t fit into the music biz machinery’s round holes. He mentions Mott the Hoople, the Stooges, Can, Amon Düül II — nearly all of which would have discernible impact on the music he made with Sonic Youth. He goes on to talk about how he values the independent shops that concentrate on some small niche, whereas Lenny Kaye appreciates the indie stores that offer a surprising variety of genres. I was left a bit worried about the state of Mike Watt’s health, but not about his passion for the music (and the community that evolves around it) that drives him; impressed by the Glenn Branca’s non-pretentious iconoclasm; and Ian MacKaye’s insouciant intellectualism. Still, in the end, no new information or insights are provided to anyone who has actually paid attention to the music business over the last few decades.