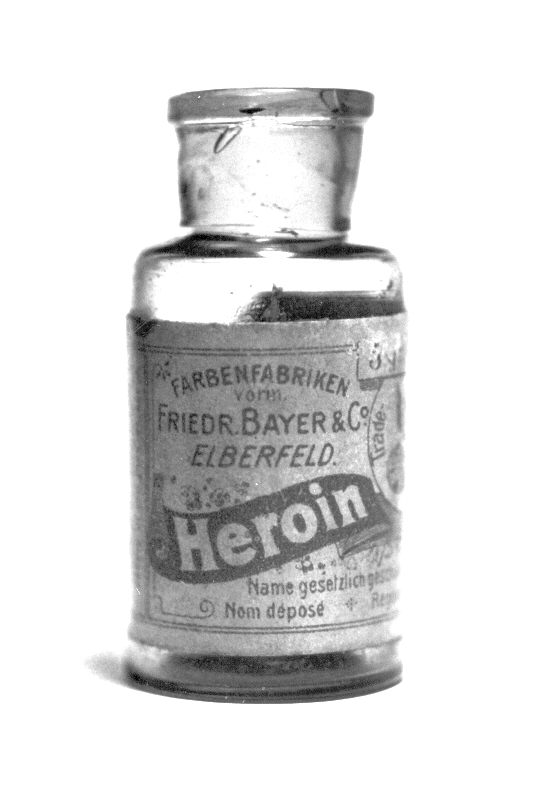

BY JEFF DEENEY FOR THE DAILY BEAST Why can’t America seem to kick its heroin habit? According to a new study, it might be because we’re not giving addicts exactly what they want: heroin, in pure, prescription form. Reported in The New England Journal of Medicine, the study provided either methadone or prescription heroin to a group of addicts who used heroin daily. Six months later, more than two-thirds of the participants who had been given prescription heroin were staying off the street version of the drug. Less than a third of the methadone group had the same success. The idea of such “heroin maintenance” programs, in which hardcore drug addicts are provided free pharmaceutical-grade heroin that they can legally inject at safe, medically staffed clinics, is gaining supporters from all corners: medical professionals, drug-policy experts, and perhaps not surprisingly, addicts themselves. Take Tattoo Mike and Bobby Dukes. Both were dopefiends and fixtures on the Philly punk scene. Intricate ink designs spill from their shoulders to their wrists—Bobby Dukes’ even climb the sides of his neck. As heroin addicts, they lived chaotic lives. Tattoo Mike was a crazy street-fighting kid in the ’90s, adamantly anti-drugs during his straight-edge teens before he rapidly progressed from downing forties of malt liquor to copping dope in the heroin-soaked Badlands of North Philadelphia. Bobby Dukes spent 15 years running with prostitutes, pimps, and hustlers, and living in gutters with hardened homeless men. MORE

BY JEFF DEENEY FOR THE DAILY BEAST Why can’t America seem to kick its heroin habit? According to a new study, it might be because we’re not giving addicts exactly what they want: heroin, in pure, prescription form. Reported in The New England Journal of Medicine, the study provided either methadone or prescription heroin to a group of addicts who used heroin daily. Six months later, more than two-thirds of the participants who had been given prescription heroin were staying off the street version of the drug. Less than a third of the methadone group had the same success. The idea of such “heroin maintenance” programs, in which hardcore drug addicts are provided free pharmaceutical-grade heroin that they can legally inject at safe, medically staffed clinics, is gaining supporters from all corners: medical professionals, drug-policy experts, and perhaps not surprisingly, addicts themselves. Take Tattoo Mike and Bobby Dukes. Both were dopefiends and fixtures on the Philly punk scene. Intricate ink designs spill from their shoulders to their wrists—Bobby Dukes’ even climb the sides of his neck. As heroin addicts, they lived chaotic lives. Tattoo Mike was a crazy street-fighting kid in the ’90s, adamantly anti-drugs during his straight-edge teens before he rapidly progressed from downing forties of malt liquor to copping dope in the heroin-soaked Badlands of North Philadelphia. Bobby Dukes spent 15 years running with prostitutes, pimps, and hustlers, and living in gutters with hardened homeless men. MORE

Editor’s Note: The following is an extended commentary by Jeff Deeney on the issue of heroin-assisted drug treatment and the obstacles to implementation such treatment will face in Philadelphia.

BY JEFF DEENEY Now that we’ve heard from policy experts and advocates about why the arrival of heroin assisted treatment is imminent in America, let me tell you why it’s not really, at least not in any meaningful way in Philadelphia. This requires me to switch hats, taking off the journalist hat the Daily Beast makes me to wear that requires me to shelve my opinions and simply present the issue and put on the social worker hat that allows me to share how I see the systems that deliver drug treatment services in big urban settings from where I sit within them. There’s probably never been a worse funding environment to attempt to start new drug treatment programs in than the current one. Municipal and state budgets basically everywhere are still completely fucked right now and reductions in services and cuts to staffing remain the norm despite what you read in the papers about economic recovery. There was an industry wide spasm last year when new state and municipal budgets were passed where entire branches of city agencies that provide addiction services found their funding cut by as much as 75% over night. Please take a moment to digest this figure. The conditions those of us who work in the trenches of this industry, providing publicly-funded services to poor, street level addicts, have dealt with over the past year are crushing. Critical services we typically access for our clients like supported housing have evaporated as entire programs have shut down or radically reduced their capacities. Our own meager salaries have been frozen, coworkers laid off. Morale is low, everyone is broke, overworked and there’s no end in sight. Everyone feels like the long-term outlook for the industry is very bleak and we are many long, hard years away from restoring comfortable funding levels.

BY JEFF DEENEY Now that we’ve heard from policy experts and advocates about why the arrival of heroin assisted treatment is imminent in America, let me tell you why it’s not really, at least not in any meaningful way in Philadelphia. This requires me to switch hats, taking off the journalist hat the Daily Beast makes me to wear that requires me to shelve my opinions and simply present the issue and put on the social worker hat that allows me to share how I see the systems that deliver drug treatment services in big urban settings from where I sit within them. There’s probably never been a worse funding environment to attempt to start new drug treatment programs in than the current one. Municipal and state budgets basically everywhere are still completely fucked right now and reductions in services and cuts to staffing remain the norm despite what you read in the papers about economic recovery. There was an industry wide spasm last year when new state and municipal budgets were passed where entire branches of city agencies that provide addiction services found their funding cut by as much as 75% over night. Please take a moment to digest this figure. The conditions those of us who work in the trenches of this industry, providing publicly-funded services to poor, street level addicts, have dealt with over the past year are crushing. Critical services we typically access for our clients like supported housing have evaporated as entire programs have shut down or radically reduced their capacities. Our own meager salaries have been frozen, coworkers laid off. Morale is low, everyone is broke, overworked and there’s no end in sight. Everyone feels like the long-term outlook for the industry is very bleak and we are many long, hard years away from restoring comfortable funding levels.

Heroin maintenance proponents can’t understand why there would be a lack of enthusiasm for what they consider a monumental development in the NAOMI (North American Opiate Medication Initiative) study published last year in the New England Journal of Medicine that showed how heroin assisted treatment can have positive impacts on the severely, chronically addiction disordered who drop out of methadone maintenance programs. They fought long and hard for this — some policy experts have been pushing these programs for more than a decade. So why am I, a social worker whose clients could benefit from heroin maintenance programs, not feeling so excited?

It’s important to note that my lack of enthusiasm doesn’t signal an ideological opposition to opiate maintenance programs (the “can’t do that here mentality” that Ethan Nadelmann of the Drug Policy Alliance speaks of). I participate in client referrals to methadone maintenance programs at my job when such referrals are clinically appropriate and have seen how they can miraculously stabilize opiate addicted clients in crisis states who need them. What dampens my enthusiasm for the prospects of new programs is the ugly financial/political realities of working in addiction services. It seems possible to me that these realities are too distant from think tank policy experts; they don’t feel them as acutely as day-to-day service providers like I do because policy experts don’t often traffic the usually dumpy clinics where the services they advocate for nationally are provided locally.

There is very little roadmap forward from the NAOMI study in terms of tackling the myriad obstacles that will meet these programs in the urban American landscape presuming, as advocates do, that they will be legally approved for deployment in the first place. Where will the funding for heroin maintenance come from in the especially resource starved environment we currently work in? How do you tackle the very real issues of scale that appeared immediately even to working class ex-dopefiend Bobby Dukes? The NAOMI study all this hubub is about was a trial administering clinic-based heroin to 115 addicts. In a city the size of Philadelphia the program would have to serve potentially 2000 clients in order to have the impact advocates anticipate. In New York, the number of qualifying addicts could be triple that. In implementing heroin maintenance you are talking about building a massive new infrastructure of service delivery at a time when up to 75% of existing services were recently eliminated. Nobody I talked to seemed able to paint a clear picture of how that kind of service delivery apparatus materializes in such an environment.

There will be political oppositions to heroin maintenance, potentially from unexpected quarters. The obvious opposition that advocates do anticipate will come from law enforcement, though advocates also stress that European law enforcement supports heroin maintenance because they see how it keeps criminality prone addicts from re-offending. I wish I could find that fact heartening but I don’t think there’s any evidence to support a connectivity between police officer mentalities overseas and the typically ex-military, conflict-oriented urban American cop. In fact, there are social workers at Penn studying police interactions with the mentally ill, who have found that while police have made big strides in terms of more compassionate interactions with those in mental health crisis, this compassion tends to disappear if drugs are discovered during the interaction. American cops are still very much behind the drug war, and I anticipate that they will be until the bitter end.

And what about the District Attorney’s Office? Will Seth Williams want to be known as the DA who “legalized heroin,” as opponents will surely frame the issue? Even abstinence oriented drug courts took years and years of strenuous arm twisting with the District Attorney’s Offices by the most politically connected judges to get up and running. Heroin maintenance is going to require tireless advocates with extraordinary influence not only at the national level, but inside the City Hall of each and every municipality that hopes to have such a program.

The less obvious potential source of political opposition is one you wouldn’t even think of unless you had experience operating within the dysfunctional local systems that provide these services. If state funding for heroin maintenance programs is administered by the same source at the county behavioral health department as methadone maintenance, the two models would likely wind up competing for the same finite pool of resources. If this is the case, and resources remain as scarce as they are right now, it’s possible to imagine a scenario where the most strenuous opposition to new heroin maintenance programs comes from within the local opiate maintenance community.

If you find this prospect inconceivable, and I think national-level heroin maintenance advocates would, then you clearly have not practiced service provision in the fiefdom-minded, dysfunction perpetuating program landscape of Philadelphia. When I was working at the grassroots level with then recently formed local family housing first provider SafeHome Philadelphia we found the greatest opponents to the growth and expansion of our program came from within our own field of practice. We were implementing an evidence-based model pioneered by a group in Los Angeles that had 20 years of history behind it. We, like heroin maintenance advocates, assumed that since we had evidence that our model worked local service providers would welcome us and our new ideas to the table as partners.

What actually happened is that other prominent local homeless services providers bashed the model in the press as a dangerous one that shouldn’t be implemented. Lacking the political clout the heads of these other agencies had, we were locked out of consideration for city funding. To me, this ice cold reception was clearly a fear-based response to what was seen by established providers as a potential new funding competitor. Welcome to Philadelphia, heroin maintenance advocates. Don’t expect other providers to make space for you at the table just because you’ve got a stack of published journal findings that say you should be there. Of course, your mileage may vary depending on the level of dysfunction in your particular municipality.

So now that I got all the bah-humbug out, what does heroin maintenance really wind up looking like, and when can we expect it in Philadelphia? The one place heroin maintenance will be well received is in the philanthropic community. This again reflects my experience with helping implement a new evidence based homeless services program in Philadelphia. When you turn away from state and municipal funding streams you leave behind all the politicking and jockeying between competing programs for bigger pie slices. While being frozen out of city funding streams, SafeHome Philadelphia was very warmly received by local foundations precisely because we had new ideas that were evidence based. We were able to get grants to keep the program thriving by providing the hard data that foundations demand, but favoritism-driven city agencies often ignore. Numbers oriented private funders will likely be the initial base of support for heroin maintenance programs, but grant funded programs are also typically small in scale and not able to meet the needs of large populations.

Unfortunately, this means that for the foreseeable future any locally implemented heroin maintenance program will be just another program with a website full of awesome sounding success testimonials that I can’t actually ever refer clients to because it’s always full. It’s frustrating to locate a new resource for your client, that is exactly the resource your client needs, only to be told that there are no openings and the wait list is two years long. But if a NAOMI-sized, grant funded heroin maintenance program is all we wind up getting in Philadelphia, that’s going to be the reality of how useful it is to a social worker like me. It’s really nothing to get that excited about. When can we expect even this much? Who knows; five years, maybe ten? It’s truly impossible to say especially considering how brutal the current funding environment is. Sorry to be the buzz kill at the free dope party.