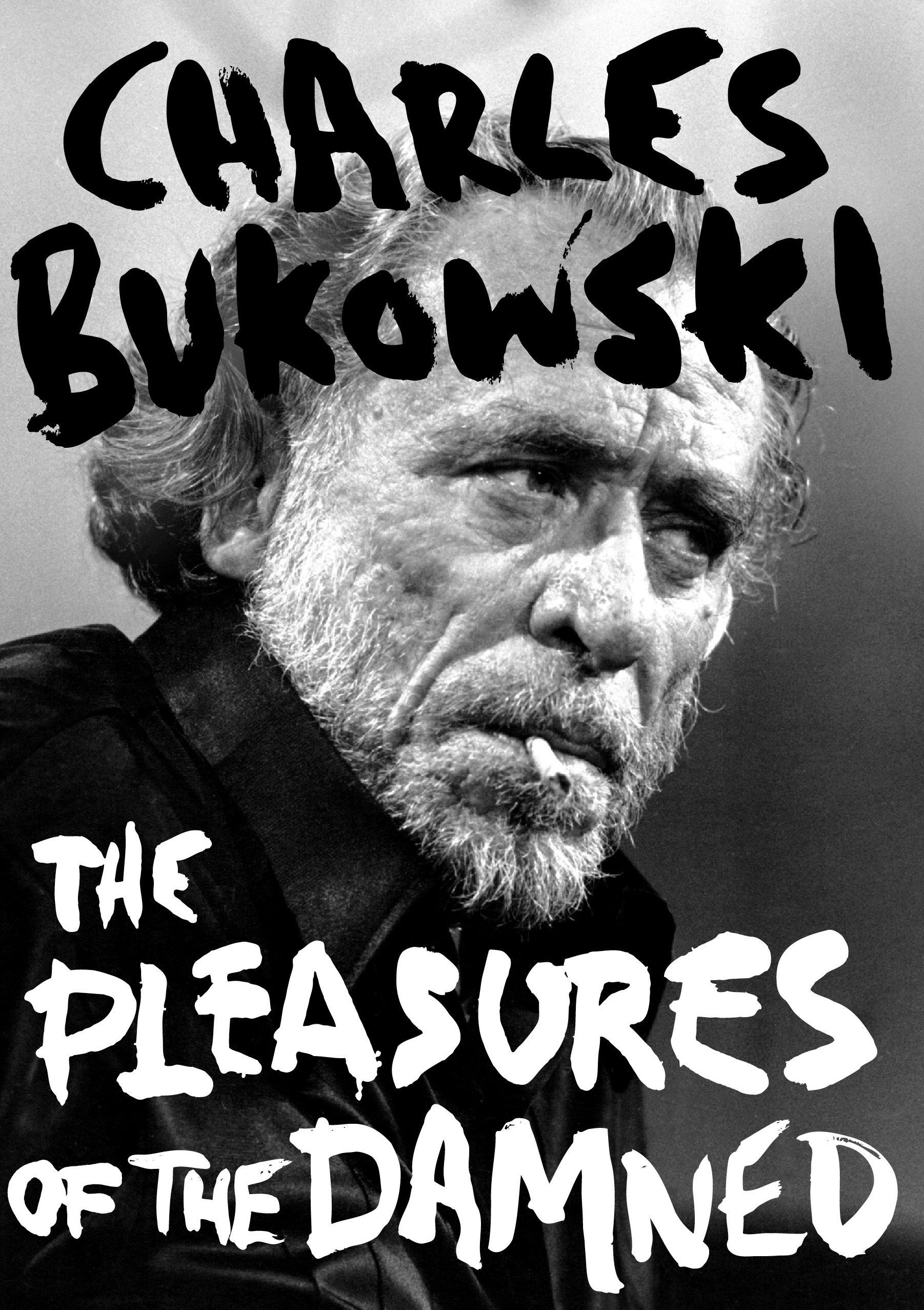

BY PAUL MAHER JR. BOOK CRITIC Charles Bukowski, the ever-prolific even in death American novelist and poet, continues to satisfy the insatiable hunger of his vast cult-audience for more, not with bottom drawer rejected pieces, but with significant work that instills into his canon an ever-growing indication of his true importance as a man of letters. The posthumous shadow he casts across American lit only continues to loom larger with each passing year. Editor David Calonne has ably compiled 39 previously-uncollected stories and essays spanning the years 1946 to 1992. The first volume, Portions From A Wine-stained Notebook (2008) demonstrates the journalist in Bukowski. He conjures the best qualities of a newsman pulling together slices-of-life, summoning his readers into a ragtag world of losers, wanna-be’s, believers and doubters, girlfriends and whores, and the ghost of his father that seems to constantly appear over his shoulder. Bukowski’s aim is unerring and he never wastes ammo, always making his point with compact, bullseye-hitting sentences that explode in the brain like verbal shrapnel.

BY PAUL MAHER JR. BOOK CRITIC Charles Bukowski, the ever-prolific even in death American novelist and poet, continues to satisfy the insatiable hunger of his vast cult-audience for more, not with bottom drawer rejected pieces, but with significant work that instills into his canon an ever-growing indication of his true importance as a man of letters. The posthumous shadow he casts across American lit only continues to loom larger with each passing year. Editor David Calonne has ably compiled 39 previously-uncollected stories and essays spanning the years 1946 to 1992. The first volume, Portions From A Wine-stained Notebook (2008) demonstrates the journalist in Bukowski. He conjures the best qualities of a newsman pulling together slices-of-life, summoning his readers into a ragtag world of losers, wanna-be’s, believers and doubters, girlfriends and whores, and the ghost of his father that seems to constantly appear over his shoulder. Bukowski’s aim is unerring and he never wastes ammo, always making his point with compact, bullseye-hitting sentences that explode in the brain like verbal shrapnel.

In abundant display is the “don’t give a fuck” attitude that makes for writing of the highest caliber. He is, I would argue, an echo of Albert Camus, in that he neither glamorizes nor sympathizes with life’s absurdities. He even references Camus’ The Stranger by addressing the  percussive impulsiveness of his life actions and the driving motivations of his literary sensibilities. Bukowski calls it “The Panic.” Blindly grappling with the stagnant realities of his personal life, he documents the withering flower of despair together with nebulous shades of hope, each overreaching, blotting the Bukowskian mindscape. Haunted by a tortured boyhood, Bukowski makes himself a poster boy for hard-knock living and the virtues of tough love. Like a brass-rail Existentialist or a skid-row Transcendentalist, he is candid, unblinking, leaving it to his readers to cast their own judgment about his mishaps, his drinking, his sexual appetite or his own pessimism. He is Ralph Waldo Emerson as a Dirty Old Man, not lounging in the grape-arbor of Concord, Massachusetts, but bent-over a table in an L.A. flophouse scribbling in pencil to the strains of Sibelius. Nowhere else will we read the perspective of an accused rapist caught with his pants down in front of a little girl after her mother bursts through the bathroom door. Buk makes it episodic and tragic, I mean,

percussive impulsiveness of his life actions and the driving motivations of his literary sensibilities. Bukowski calls it “The Panic.” Blindly grappling with the stagnant realities of his personal life, he documents the withering flower of despair together with nebulous shades of hope, each overreaching, blotting the Bukowskian mindscape. Haunted by a tortured boyhood, Bukowski makes himself a poster boy for hard-knock living and the virtues of tough love. Like a brass-rail Existentialist or a skid-row Transcendentalist, he is candid, unblinking, leaving it to his readers to cast their own judgment about his mishaps, his drinking, his sexual appetite or his own pessimism. He is Ralph Waldo Emerson as a Dirty Old Man, not lounging in the grape-arbor of Concord, Massachusetts, but bent-over a table in an L.A. flophouse scribbling in pencil to the strains of Sibelius. Nowhere else will we read the perspective of an accused rapist caught with his pants down in front of a little girl after her mother bursts through the bathroom door. Buk makes it episodic and tragic, I mean,

Bukowski’s hard-earned contempt for the old guard elites of the literary critic industrial complex is also well-represented in this collection. In “Manifesto: A Call For Our Own Critics” he declares:

The fresh air of a new culture, the magnetism and meaning and hope, the exactness of our energies—these things haven’t, in any sense, been harnessed or realized. And until they are. . . .five or six old men, craggy and steatopygous in University chairs, will be the hierophants of our poetic universe.

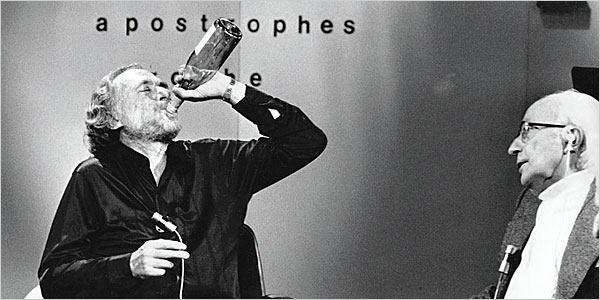

Oh, to be a fly on the wall at a summit meeting between Bukowski and Harold Bloom, just to see who’s left standing. Bukowski’s embracing of Nietzsche’s dictum from Also Sprach Zarathustra — “Of all that is written I love only what a man has written with his blood” — sorted out the pale pretenders from the steely practitioners. The collection of interviews between Barbet Schroeder and Charles Bukowski, available on DVD (The Charles Bukowski Tapes), first drove that point home to me, and this book and its previous volume confirms it. Buk never sold out, never went soft. He even sets out to defang the author that was once the scorn of respectable book shops and lending libraries across the country, Henry Miller. Miller, it seems, isn’t interesting at all to Buk:  “You know, I wonder if Henry Miller is really all that good? I’ve tried to read his books on cross-country buses but when he gets into those long parts in between sex he is a very dull fellow indeed. On cross-country buses I usually have to put down my Henry Miller and try to find somebody’s legs to look up, preferably female.”

“You know, I wonder if Henry Miller is really all that good? I’ve tried to read his books on cross-country buses but when he gets into those long parts in between sex he is a very dull fellow indeed. On cross-country buses I usually have to put down my Henry Miller and try to find somebody’s legs to look up, preferably female.”

Though he always bristled at being labeled a Beat Generation writer, Buk’s unabashed references to sex, drugs and alcohol echoes portions of Jack Kerouac’s Visions of Cody, a posthumous masterpiece that Kerouac considered his one great book. This is, as Calonne points out, where these two craft-masters finally meet. Unlike Kerouac, Buk’s writing is less dependent on spontaneity than it is at drawing from a deep well of raw talent. His is an ability to describe both his outer and inner worlds with scary lucidity. And he was unflinching. In one passage, Bukoswki reaches Burroughsian heights, almost sounding like ole’ El Hombre Invisible at times: “Did I ever tell you about the 6-foot-2 sailor who got so jaded with dick he took a guy’s arms up his ass, right up to the elbow?” he wrote in the 1970 article “The Cat in the Closet.” That’s pure Buk: shocking yet undeniably true to form, and, most importantly, still bleakly hilarious 40 years later. Together with its first volume (and I hope there are more to come!), this makes absolute required reading, not only for the Bukowski fanatics, but also by jaded readers who have been stupefied into what good reading should be by our pale pretenders.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Paul Maher Jr. is the writer of two biographies of Jack Kerouac, the editor of two volumes of interviews with Kerouac and Miles Davis and another with Tom Waits due out in fall 2010. He is also a photographer. Maher is currently working on two screenplays about the captivity of Mary Rowlandson and the prison years of Dostoevsky.