When You’re Strange screens at 8:30 PM tonite at the Piazza

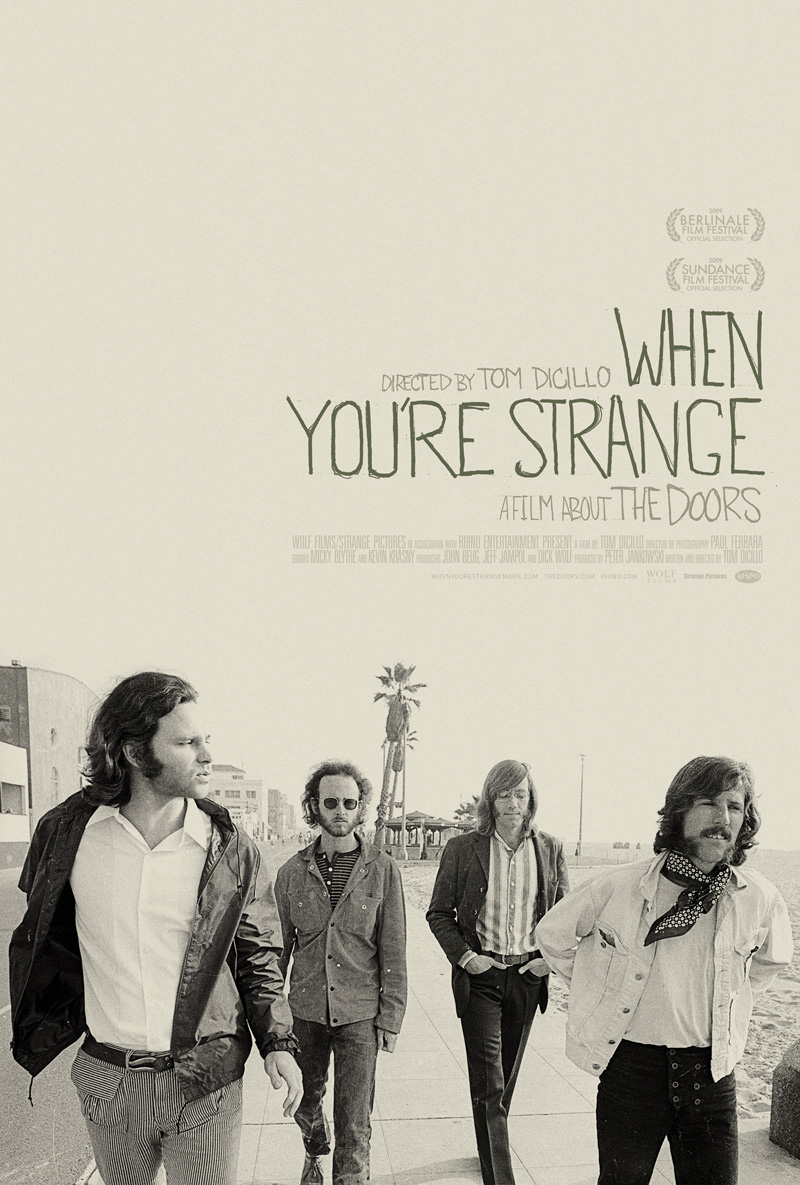

WHEN YOU’RE STRANGE (2009, directed by Tom Dicillo, 90 minutes, U.S.)

THE ECLIPSE (2009, directed by Conor McPherson, 88 minutes, Ireland)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

Some things never change. He’s still hot, he’s still sexy and he’s still dead yet I was still hoping that this new documentary on Jim Morrison, the lead singer of the 60’s pop band The Doors, would give us some original angle on the much-mythologized rock casualty. Perhaps the fact that it is distributed by Rhino Entertainment should have been a warning: When You’re Strange is a shallow re-telling of the legend of the Lizard King designed to maximize the sales of t-shirts, CDs and mp3 downloads. As a promo item the film might be a resounding success but it does little to illuminate the guy behind the pursed-lips pose.

Composed entirely of footage from The Doors four-year heyday (no talking heads, for better or for worse), When You’re Strange reiterates the same poet/shaman/existential explorer persona that has been fabricated and milked now for thirty years, when Jerry Hopkins first resurrected Morrison in his best-selling biography No One Here Gets Out Alive. By the time Oliver Stone turned the band’s tale into a hirsute big-screen opus in 1991, the inadvertent humor of a drunk in his mid-twenties thinking he was Rimbaud was apparent to everyone except stoner teens and Stone himself. Director Tom DiCillo (taking an odd side-trip from his filmography of N.Y.C. indies like Living in Oblivion and Johnny Suede) chops the vintage footage into a quick edit frenzy, catching Jim jumping, diving and rolling and especially standing still, all in the effort present him as the ultimate “heavy cat” living too hard and loving too fast.

But enough with kicking a guy while he is dead. Although what DiCillo does with the footage is uninspiring The Doors themselves are as entertaining as ever, despite their lunk-headed pretensions and Jim’s descent into booze-addled incoherency. Morrison is frozen in time, looking as handsome as Michelangelo’s marble and the band’s catalog of tunes and their organ-driven sound remain striking and unique. The biggest find is footage from HWY, an experimental film of Jim shot in gorgeous sun-bleached colors as he zooms around the desert in a souped-up car screaming and looking cool. There is also an extended look at some of the dicey shows The Doors played when Jim’s behavior became unpredictable, egging on near-riots in New Haven and maybe (though probably not) whipping out his Jim-hood on stage in Miami. As interesting as the footage sometimes is, the narration from Johnny Depp is embarrassingly fawning, spouting cliches like “you can’t burn out unless you’re on fire” and the stock footage of sixties-era iconic events, Vietnam bombings, Kent State shooting and the like, just cement the feeling that the filmmakers haven’t digested the Doors meaning, they’re just regurgitating second-hand perceptions.

Jimbo does get in one telling moment before the film’s closing. Toward the end of his life the star machine seems to have exhausted him to the extent that even he questions his endless image-fluffing for the cameras. “All that posing: what was I thinking?” But before he could sort out his thoughts he was gone, leaving this handsome but empty documentary to do the posing for him.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Also trafficking in ghosts is The Eclipse, a quietly odd film out of Ireland directed by acclaimed playwright Conor McPherson. Giving a rare lead to large-headed character actor Ciarán Hinds, The Eclipse is a delicate little tale about a widowed father Michael, who volunteers at a writer’s festival in his small seaside town. Michael gets involved with Lena (Iben Hjejlea, a charming actress unknown stateside), who is trying to avoid getting re-entangled with a fellow writer, the married Nicholas (the dependable Aidan Quinn).

The trio of actors are truly magnificent in a un-showy and quiet way, and such detail is given to their flirtations and concerns that it is jarring when Michael begins being haunted by ghosts, who jump out him as forcefully as anything in a Nightmare on Elm Street film. Lena has written a book about spectral spirits so she makes a perfect shoulder for Michael and tying things up neatly, the heatedly-amorous Nicholas describes himself as “haunted” by his brief affair with Lena. These two plots, the quiet mid-life romance and the spooky hyperactive ghost story, make for odd bedfellows but if you can live with these two tales shacking up together The Eclipse has some somber and moving things to say about apparitions, memory and loss.

SALON: “When You’re Strange” consists almost entirely of archival material: home movies and photos, concert and rehearsal footage, period TV broadcasts, even clips from a UCLA student film in which Morrison appeared before he became famous. Especially since we’re talking about a band whose entire career spanned less than five years (from early 1967 to Morrison’s death in the summer of ’71), this strategy collapses the historical distance between us and the Doors, and spares us the morass of maudlin pseudo-Proustian reflection into which many such pop-nostalgia films tumble. Furthermore, this underscores the ways that Morrison, in all his confusion and self-contradiction — reclusive poet, leather-clad sex god, reluctant celebrity, abusive drunk, pop star with limited musical gifts — remains a vital cultural force, the conscious or unconscious model for many rock stars, actors or rappers who came later. MORE