[Artwork by KURT KAUPER]

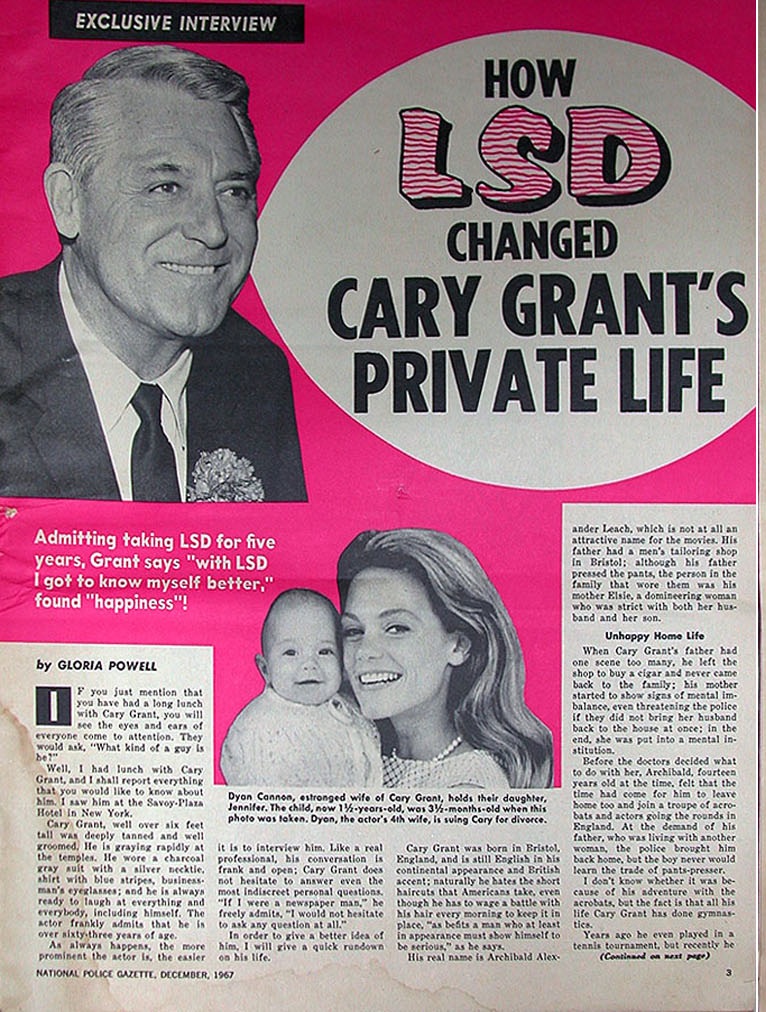

WFMU: It was 1943. Cary Grant was starring in the motion picture Destination Tokyo; an action-filled wartime drama co-starring John Garfield and a deluge of racial slurs. While America was embroiled in the intense fighting of World War Two, Axis powers had surrounded the neutral country of Switzerland. Deep within Nazi surrounded boundaries, Swiss chemist Albert Hoffman was busy toiling away in a dimly lit laboratory, about to study the properties of a synthesis he had abandoned five years earlier. Hoffman was trying to devise a chemical agent that could act as a circulatory and respiratory stimulant when he accidentally absorbed lysergic acid through his fingers. While Americans sat in darkened theaters enjoying Cary Grant’s portrayal of a submarine captain, Hoffman was experiencing accelerated thought patterns, polychromatic visions and an unbearable onslaught of intense emotion. This  was the world’s first acid trip. The discovery was soon to transform the life of one of Hollywood’s most glamorous stars. Cary Grant was the first mainstream celebrity to espouse the virtues of psychedelic drugs. Whereas novelist Aldous Huxley’s famous 1954 treatise The Doors of Perception recounted his remarkable experiences with mescaline, Huxley was hardly mainstream – a darling of intellectual circles to be sure, but a far cry from a matinee idol. Grant was one of the biggest stars Hollywood had to offer when he jumped headlong into Huxley’s Heaven and Hell. His endorsement of subconscious exploration, arguably, created more interest in LSD than Dr. Timothy Leary who was largely preaching to the converted.1 Grant on the other hand was the fantasy of countless Midwestern women. He convinced wholesome movie starlets like Esther Williams and Dyan Cannon to blow their minds. When Ladies Home Journal and Good Housekeeping interviewed him, the topic of conversation wasn’t Cary’s favorite recipe or “the problem with youth today.” Instead, Cary Grant was telling happy homemakers that LSD was the greatest thing in the world. MORE

was the world’s first acid trip. The discovery was soon to transform the life of one of Hollywood’s most glamorous stars. Cary Grant was the first mainstream celebrity to espouse the virtues of psychedelic drugs. Whereas novelist Aldous Huxley’s famous 1954 treatise The Doors of Perception recounted his remarkable experiences with mescaline, Huxley was hardly mainstream – a darling of intellectual circles to be sure, but a far cry from a matinee idol. Grant was one of the biggest stars Hollywood had to offer when he jumped headlong into Huxley’s Heaven and Hell. His endorsement of subconscious exploration, arguably, created more interest in LSD than Dr. Timothy Leary who was largely preaching to the converted.1 Grant on the other hand was the fantasy of countless Midwestern women. He convinced wholesome movie starlets like Esther Williams and Dyan Cannon to blow their minds. When Ladies Home Journal and Good Housekeeping interviewed him, the topic of conversation wasn’t Cary’s favorite recipe or “the problem with youth today.” Instead, Cary Grant was telling happy homemakers that LSD was the greatest thing in the world. MORE

CARY GRANT: Under the effect of LSD 25, these dreams or hallucinations, if you wish, are speeded up, and interpreted, when properly conducted ba a psychiatrically orientated doctor who sits quietly by, awaiting whatever communication one cares to make — the revealing of a hidden memory seen again from an older, more mature viewpoint, or the dawning of new enlightenment. Then, if the doctor is as skilled as mine was, he carefully proffers a word or key, that can lead to the next release, the next step toward fuller understanding. The shock of each revelation brings with it an anguish of sadness for what was not known before in the wasted years of ignorance and, at the same time, an ecstasy of joy at being freed from the shackles of such ignorance. One becomes a battleground of old and new beliefs. Of nightmares beyond description. I passed through changing seas  of horrifying and happy sights, through a montage of intense hate and love, a mosaic of past impressions assembling and reassembling; through terrifying depths of dark despair replaced by glorious heavenlike religious symbolisms. Session after session. Week after week. I learned may things in the quiet of that small room. I learned to accept the responsibility for my own actions, and to blame myself and no one else for circumstances of my own creating. I learned that no one else was keeping me unhappy but me; that I could whip myself better than any other guy in the joint. I learned that all clichés prove true; which is, of course, the reason for their repetition, even when the meaning has been forgotten by the constant usage.I learned that everything is, or becomes, its own opposite. A theory I can sometimes apply, but would find difficult to convey. For a slow learner, I learned a great deal — and the result of it all was rebirth. A new assessment of life and myself in it. An immeasurably beneficial cleansing of so many needless fears and guilts, and a release of the tensions that had been the result of them. Not a cleansing and release of them all, certainly, for that would be the absolute — the innocence of the newly born baby with an unformed ego still close to God — and I cannot experience the absolute until I have unreservedly returned to the comfort of God. In life there is no end to getting well. Perhaps death itself is the end to getting well. Or, if you prefer to think as I do, the beginning of being well. MORE

of horrifying and happy sights, through a montage of intense hate and love, a mosaic of past impressions assembling and reassembling; through terrifying depths of dark despair replaced by glorious heavenlike religious symbolisms. Session after session. Week after week. I learned may things in the quiet of that small room. I learned to accept the responsibility for my own actions, and to blame myself and no one else for circumstances of my own creating. I learned that no one else was keeping me unhappy but me; that I could whip myself better than any other guy in the joint. I learned that all clichés prove true; which is, of course, the reason for their repetition, even when the meaning has been forgotten by the constant usage.I learned that everything is, or becomes, its own opposite. A theory I can sometimes apply, but would find difficult to convey. For a slow learner, I learned a great deal — and the result of it all was rebirth. A new assessment of life and myself in it. An immeasurably beneficial cleansing of so many needless fears and guilts, and a release of the tensions that had been the result of them. Not a cleansing and release of them all, certainly, for that would be the absolute — the innocence of the newly born baby with an unformed ego still close to God — and I cannot experience the absolute until I have unreservedly returned to the comfort of God. In life there is no end to getting well. Perhaps death itself is the end to getting well. Or, if you prefer to think as I do, the beginning of being well. MORE