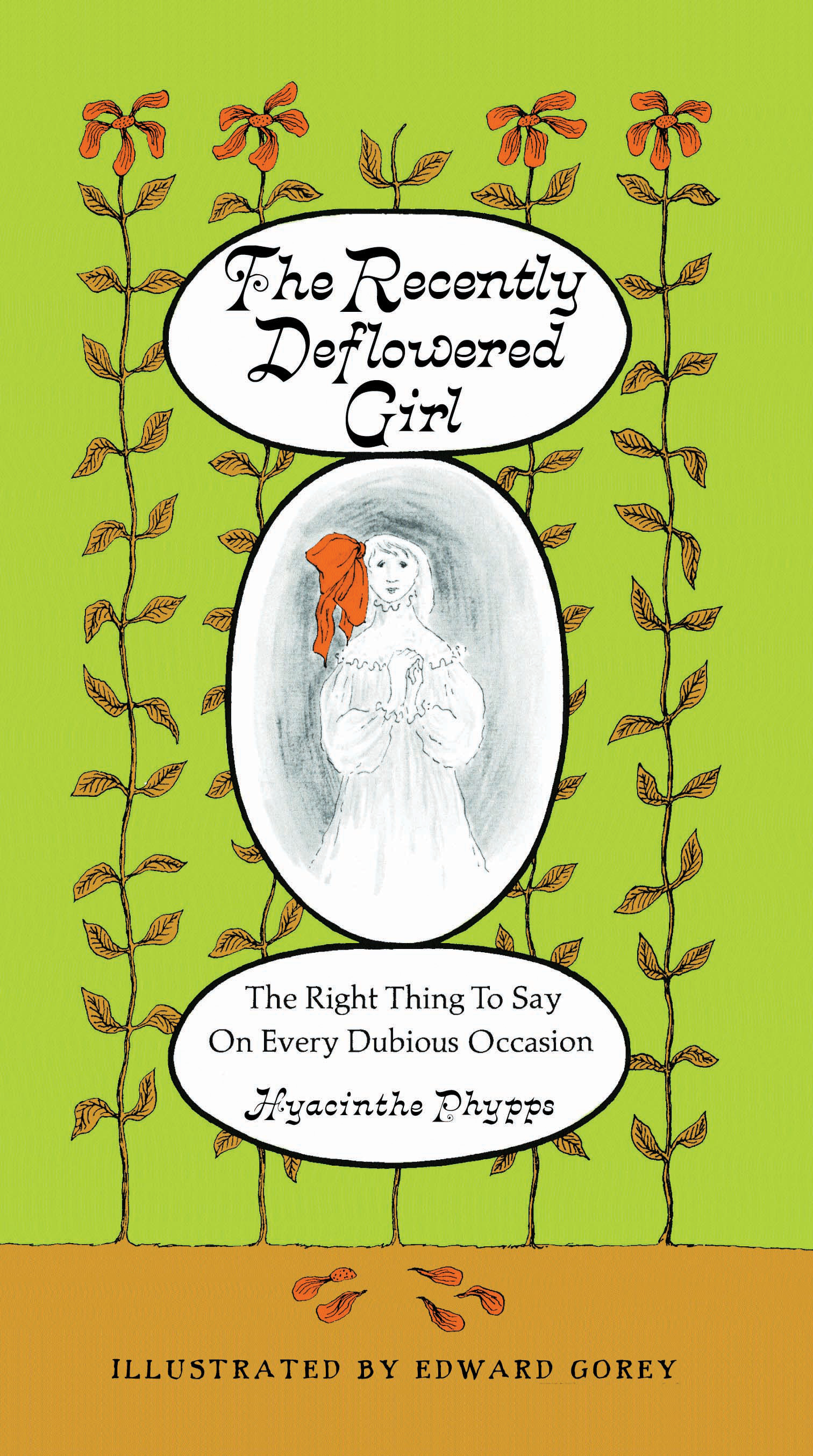

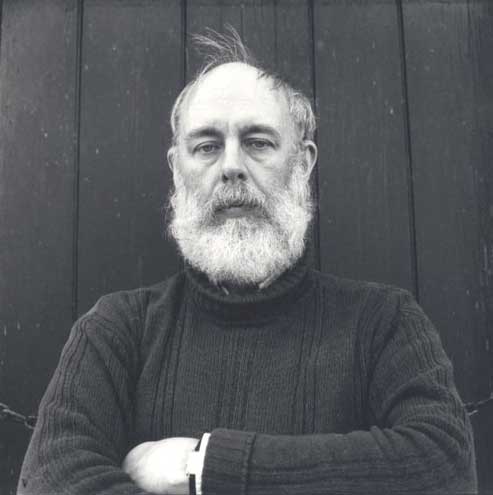

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA Edward Gorey was a lot of things — illustrator, author, designer, screenwriter, animal lover, pop culture junkie, antiquarian aesthete — but above all else, he was, for better or worse, the post-modern godfather of goth, a lineage that stretches back to Edgar Allan Poe, the pre-modern godfather of goth. Absent Gorey’s meticulously cross-hatched pen-and-ink chiaroscuros — typically exquisitely gloomy drawing room interiors and the forlorn coal-eyed waifs that haunt them — there would be no Tim Burton. Though he illustrated and authored countless books from the 1950s through the 1990s, and continued re-packaging and publishing his work up until his death in 2000, Gorey’s touchstone work will forever be The Gashlycrumb Tinies, a splendidly macabre illustrated alphabet book wherein 26 children, each one named after a letter of the alphabet, die in ways both devious and dastardly. Late last year, Bloomsbury re-published The Recently Deflowered Girl, a faux -advice book for young women navigating the newly opened world of sexuality. Originally published in 1965 and long since forgotten, the book features Gorey’s renderings of the recently de-virginized girls, the unlikely suitors, and the outlandish settings where the dirty deed got done. The accompanying nudge-nudge-wink-wink text by Hyacinthe Phypps (aka Mel Juffe ) counsels the freshly deflowered ladies on how best to extricate themselves from these unseemly assignations with whatever is left of their dignity and pride. Back when it was originally published, The Recently Deflowered Girl was an amusing harbinger of the then-blossoming sexual revolution. Today, in age of sexting and Viagra ads on prime time, it is amusing for a whole other set of reasons — reasons that we asked Bloomsbury editor Margaret Maloney to explain. It was Maloney who helped shepherd the book from the outer reaches of the Internet, where it was first re-discovered, to a Barnes & Noble near you.

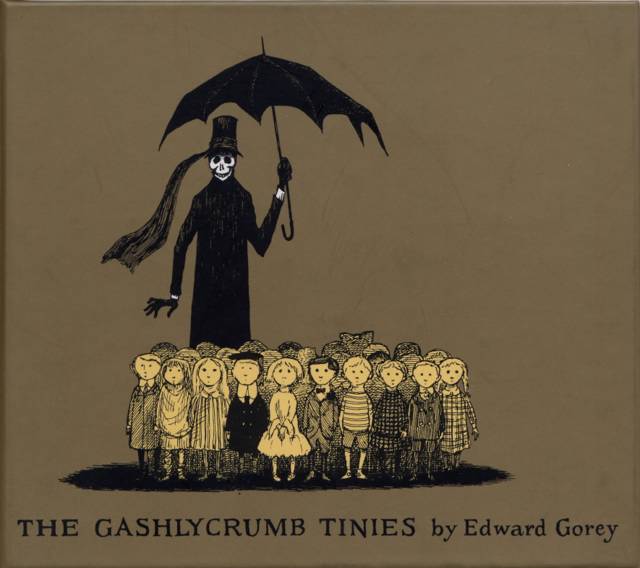

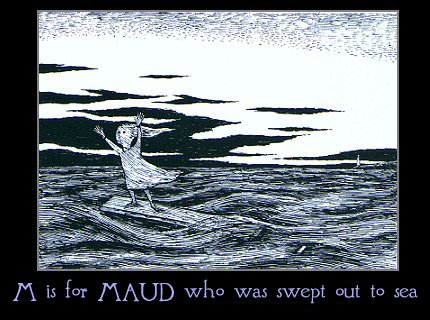

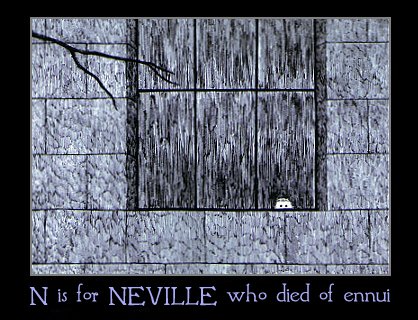

BY JONATHAN VALANIA Edward Gorey was a lot of things — illustrator, author, designer, screenwriter, animal lover, pop culture junkie, antiquarian aesthete — but above all else, he was, for better or worse, the post-modern godfather of goth, a lineage that stretches back to Edgar Allan Poe, the pre-modern godfather of goth. Absent Gorey’s meticulously cross-hatched pen-and-ink chiaroscuros — typically exquisitely gloomy drawing room interiors and the forlorn coal-eyed waifs that haunt them — there would be no Tim Burton. Though he illustrated and authored countless books from the 1950s through the 1990s, and continued re-packaging and publishing his work up until his death in 2000, Gorey’s touchstone work will forever be The Gashlycrumb Tinies, a splendidly macabre illustrated alphabet book wherein 26 children, each one named after a letter of the alphabet, die in ways both devious and dastardly. Late last year, Bloomsbury re-published The Recently Deflowered Girl, a faux -advice book for young women navigating the newly opened world of sexuality. Originally published in 1965 and long since forgotten, the book features Gorey’s renderings of the recently de-virginized girls, the unlikely suitors, and the outlandish settings where the dirty deed got done. The accompanying nudge-nudge-wink-wink text by Hyacinthe Phypps (aka Mel Juffe ) counsels the freshly deflowered ladies on how best to extricate themselves from these unseemly assignations with whatever is left of their dignity and pride. Back when it was originally published, The Recently Deflowered Girl was an amusing harbinger of the then-blossoming sexual revolution. Today, in age of sexting and Viagra ads on prime time, it is amusing for a whole other set of reasons — reasons that we asked Bloomsbury editor Margaret Maloney to explain. It was Maloney who helped shepherd the book from the outer reaches of the Internet, where it was first re-discovered, to a Barnes & Noble near you.

PHAWKER: First of all, for the reader’s benefit, can you give a little summation of who Edward Gorey was and what his aesthetic was all  about.

about.

MALONEY: Edward Gorey was an illustrator whose career spanned from the fifties until he died in 2000. A lot of people who have seen his work but don’t know anything about him assumed he was active much earlier because his aesthetic is rooted in this earlier style of illustration. His work is all sort of dark, but with a funny twist. Everything is humorous in its own way, and it very much comes from his obsession with earlier periods of art and illustration.

PHAWKER: How did you get into Edward Gorey?

MALONEY: Just as a reader, I guess the first thing I came across where I knew “this is Edward Gorey and this is what he’s done” is when I was in college and a friend of mine had a poster on her wall of The Gashlycrumb Tinies, which is one of his books in which I believe 26 children, [with names that run the gamut from] A through Z, are killed in interesting ways. That was my first introduction to him where I knew who he was. I think that’s a very common introduction. People come across him when they’re teenagers or in college, and it’s sort of his more macabre, twisted stuff that that audience is sort of drawn to. I think it has a connection to the same kind of folks who are really into Tim Burton and The Nightmare Before Christmas. As far as how I came to this particular project, it was sort of like everyone else. I constantly read things I come across on the Internet, and I saw this thing that everyone was linking around about The Recently Deflowered Girl. Someone had scanned the entire book, which is very short, and put it up online. I read it, enjoyed it, and thought: this is fun. It didn’t actually occur to me to think about getting it republished. It wasn’t until a few weeks later that another editor at Bloomsbury, Nick Trautwein, who has since moved on elsewhere, went about pursuing the rights to republish it. There were a number of publishing houses interested in doing it. We were one of several.

PHAWKER: When was this, that it popped up on the Internet?

MALONEY: This was, I think, in January of 2009. This is an unsubstantiated story in that it was posted on the Internet, but this young woman, apparently a friend of hers had a copy of the book either through her grandmother or landlord. They found it, thought it was really great, and seeing it was out of print thought that other people should see this, scanned it and put it up online. They didn’t think anyone beyond their immediate circle of friends would read it. Then, it was the kind of thing where people were so enchanted by it and thought it was so funny and brave that they decided to pass it along to their friends, so it grew in this viral sort of way. One of the key ways that it was picked up was a blogger by the name of Joey de Villa who wrote about it, and incorporated the original post since it was off someone’s LiveJournal. Once it got really big, it got taken down for the fact that they were in violation of copyright. However Joey de Villa had it up on his blog, and that’s where people were going to look at it.

PHAWKER: What is his blog called?

PHAWKER: What is his blog called?

MALONEY: I think it’s called The Adventures Of The Accordion Guy of the 21st Century. It no longer has the entire book, because once it became widely known that it was up there, the Gorey Estate’s lawyers requested that he take down about 80% of the book. From the publisher’s perspective, we probably wouldn’t be republishing this book if it wasn’t for this viral interest on the Internet. Once something is on the Internet, it’s hard to get off. I’m glad the estate decided to give a little teaser rather than remove the entire thing. Again, from the publisher’s perspective, taking it offline would be hypocritical because that’s the reason there was any interest in it in the first place. It wouldn’t have bothered me if the whole thing had stayed up, but I understand the estate wanting to repossess it because of copyright. Something that people don’t know is that any proceeds that are made off the estate of Edward Gorey’s books go to his charitable trust and are used for animal welfare causes. Gorey was a huge animal lover, particularly cats, so all the proceeds from his books go to support animal charities. As trustees of his estate, their goal is to pull in as much money as possible for these charities.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about the actual premise of his book. How would you describe The Recently Deflowered Girl?

MALONEY: Before we talk about the premise of it, one thing I want to make clear is that this isn’t just an Edward Gorey book. Gorey didn’t write it. It was written by a man named Mel Juffe under a pseudonym. When it started going around the Internet, a lot of people just assumed that this was a Gorey book, that he illustrated and wrote it because he did write and illustrate many of his own.Juffe was a journalist and a writer who wrote for a number of different papers. He also wrote a comic novel titled Flash and a whole bunch of magazine articles and was one of these guys who was just sort of everywhere. People associate this book so strongly with Gorey because the illustrations are such a huge part of it. However, the premise of it and the real humor of it all belong to Mel Juffe.

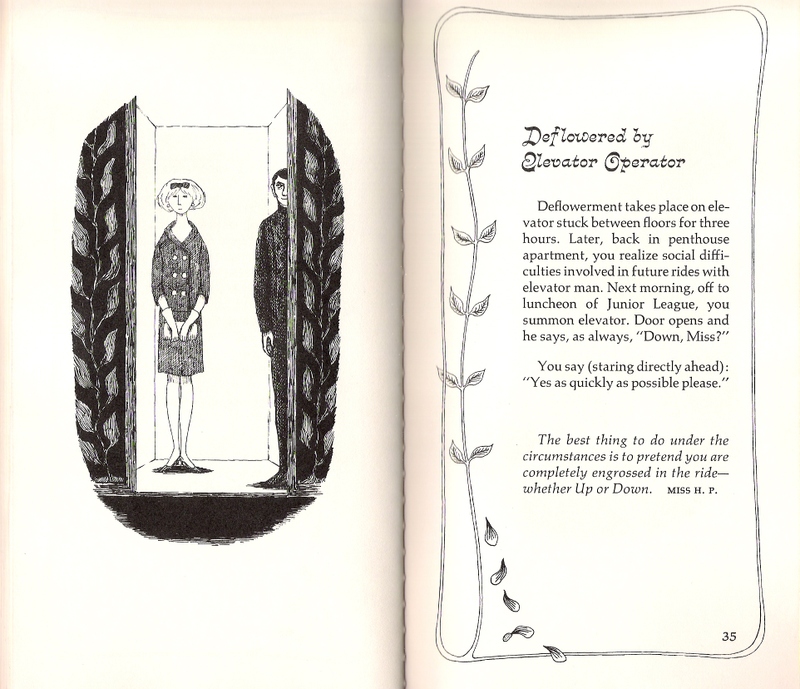

So, to answer your question about the premise of the book — it’s sort of meant to be a romantic advice book for young women. It’s done in the style and tone of, say,  Emily Post’s columns where someone writes in and explains their situation and asks what they should do to fix it. Like how they obey the rules of etiquette in each situation. In the section across from the title page, Gorey has done a watercolor of Hyacinthe Phypps , the woman who is supposed to be giving this advice. He’s done her up in full Edwardian style; high collars and a big hat with flowers. The wonderful twist about it is that it’s about all these sexual situations these women find themselves in. They’re losing their virginity to all these men, and Hyacinthe Phypps, aka Mel Juffe , offers these outrageously glib responses to these situations. I think one of the things that makes this very popular now is that, well, there’s a reason for this book not being reprinted for some time, other than just being forgotten. It was initially printed in 1965 at the height of the sexual revolution, but for a while thereafter, it seemed very dated. It has become popular again in a certain way because [the girls’ situations] aren’t all bad things [anymore]. It isn’t a problem, and it’s funny now for different reasons than it was in 1965.

Emily Post’s columns where someone writes in and explains their situation and asks what they should do to fix it. Like how they obey the rules of etiquette in each situation. In the section across from the title page, Gorey has done a watercolor of Hyacinthe Phypps , the woman who is supposed to be giving this advice. He’s done her up in full Edwardian style; high collars and a big hat with flowers. The wonderful twist about it is that it’s about all these sexual situations these women find themselves in. They’re losing their virginity to all these men, and Hyacinthe Phypps, aka Mel Juffe , offers these outrageously glib responses to these situations. I think one of the things that makes this very popular now is that, well, there’s a reason for this book not being reprinted for some time, other than just being forgotten. It was initially printed in 1965 at the height of the sexual revolution, but for a while thereafter, it seemed very dated. It has become popular again in a certain way because [the girls’ situations] aren’t all bad things [anymore]. It isn’t a problem, and it’s funny now for different reasons than it was in 1965.

PHAWKER: Like you were saying, it has this faux-Edwardian vibe but the book is coming out at the onset of the sexual revolution. The book reminds me of sort of old Playboy cartoons from that period. There’s this new sort of casualness about sexuality.

MALONEY: Back then, no one would have dared write to an etiquette column about these things, and even if they had, they wouldn’t be answered. No one would publish a question like that. Of course now we have people like Dan Savage and many others like him who do this kind of thing. Hyacinthe was just a fantastic invention when the book was published but now she actually exists, or people like her. I think that’s one of the things that makes it popular again. The questions that are asked are almost legitimate. They could potentially be asked in a sex column these days.

PHAWKER: Was there any controversy when it was first published?

MALONEY: I think it was such a small publication, [that] if there was, it wasn’t big enough to leave a mark. I think when it was published it was intended to be very campy. It wasn’t a big publishing house, it was a small press. I doubt it had reached into many parts of the country, selling mainly in New York where it was unlikely to spark any outrage.

PHAWKER: Curiously, for a guy who published a book about sex and sexuality, Gorey characterized himself as being asexual. He never married or had children.

MALONEY: I think people were fascinated by that. I don’t know what his story was beyond that, but I do think Gorey was very aware that people want to categorize people. They want to say you’re gay, straight, or whatever. These days we have more boxes than before, but people still have that desire to put you in one. I think he was very aware that people couldn’t put him in a box. They wanted to. Perhaps one of the reasons this project attracted him, beyond the fact that Gorey was very prolific in his career and illustrated for a lot of people, was that he enjoyed playing with sexuality. One of his books, I think The Curious Sofa, it’s probably the book that plays with that most directly. The Curious Sofa is an Edward Gorey book through and through. It’s one of his own works, and it is one of the dirtiest books you can imagine. However, the dirtiness is all in the mind of the reader. Everything is implied, all these people going off to places and it’s left to the reader’s imagination that they’re all having these great big orgies. It’s not actually on the page, but it’s all in the reader’s head. I think he had great fun with that book. Unlike with The Recently Deflowered Girl, there was some controversy over that book. He would say people were up in arms about it, but it was all in their heads. Nothing was explicitly stated. He didn’t reveal himself to a lot of the world, so he would always say ‘look at my work, all the answers to your questions are in there.’ Which is another way of saying ‘look inside yourself.’ I think that’s a big thing about Gorey is to always take a second look. I’m sure that even though The Recently Deflowered Girl was something he illustrated for someone else, that doesn’t mean that he wasn’t working on multiple levels with his illustrations. They’re all very much his style. There’s a lot to find in them other than just what’s on the surface.

PHAWKER: He published alot of stuff under pen names. Was that just his sense of whimsy and fun or was that for legal reasons?

MALONEY: It wasn’t for legal reasons. He did have a great sense of whimsy and fun, but I think it plays into this sense that he was constantly working on multiple levels, incorporating puzzles and things into his work. To a certain degree, by having all these pseudonyms and anagrams, he sort of is saying ‘try and find me.‘ He is very much obsessed with his public image and the way people perceived him and what’s real and what isn’t.

PHAWKER: I read that he wrote movie reviews under a pseudonym.

MALONEY: Gorey was a great consumer of culture. In The Recently Deflowered Girl, he did each of the illustrations in a different style, some of them imitating different artists or different genres of art. Beyond visual art, he was hugely into theater, opera and ballet. He was a fixture at Lincoln Center. People expected to see him there all the time.

PHAWKER: People often confuse him with Charles Addams. Was there any connection between the men?

MALONEY: Not that I’m aware of. They were both published in the New Yorker. They’re actually very different. I think people confused them because they both have this dark sensibility, but they come from different places. With Addams, there was always this play on the same incongruity. The Addams Family, in particular, was about these horrifying people who do horrible things in a mundane setting. That was sort of over and over again what his work hinged on. With Gorey, there’s a lot more going on. Some of it is certainly based on that incongruity, but there are plenty of works that aren’t macabre in any way.

PHAWKER: Today he is regarded, not surprisingly, as a goth icon, sort of the godfather of Tim Burton. There’s a great quote from him in response to the darkness in his work: “If you’re doing nonsense it has to be rather awful because there’d be no point. I’m trying to think if there’s sunny nonsense, sunny funny nonsense for children. Oh, how boring. As Schubert said, ‘There is no happy music’. That’s true, there really isn’t. And there’s probably no happy nonsense either”

MALONEY: That’s very Gorey. He just did what he liked, and found that this was something worthwhile and interesting. A lot of his books deal with death, and there are people who have a problem with that. There are people who say “Why do you have to do that?” For example in one of his alphabet books, there’s an illustration of a man in a trench coat with his back to the reader, holding the trench coat open in front of a small child, implying, of course, that he’s naked under the coat. Some of the people who can stomach the death and more macabre aspects of his work find that to be completely over the line. His point is sort of that this is the world and that’s what is in it. He doesn’t want to whitewash it and he wants to show the world as it is. He found humor in things that other people find revolting.

PHAWKER: On a related note, do you think that Edward Gorey could have gotten away with that stuff today? Would there be different roadblocks, or would there be a lack of interest from publishers?

PHAWKER: On a related note, do you think that Edward Gorey could have gotten away with that stuff today? Would there be different roadblocks, or would there be a lack of interest from publishers?

MALONEY: I think that his career would have been very different, but not impossible. I think it might be more possible now than at the time. The sensibilities he was playing with might be different because a lot of the things he was obsessed with grew out of what was already in the past when he was a child. His recurring obsessions were the things of his parents’ generation. I think that Gorey’s career would have been possible, but the bottom line is that Gorey was Gorey, and I think the answer to that question is that regardless of how successful he was, he would be doing the same thing.

PHAWKER: Is the notion that the bulk of his work was co-mingling children with these darker adult themes accurate, or is that a distortion?

MALONEY: I think that’s a distortion. For the most part, he didn’t write his books for children. Children show up a lot in his work, but I think there are only a handful of books he wrote that are specifically for kids. Most of the time when there is a sense of outrage over Edward Gorey is when people make the mistake of assuming his books are for children. They’re very much for Edward Gorey and what he found interesting and what he wanted to see. It didn’t exist, so he made it.

PHAWKER: Apparently there is an unproduced screenplay for a silent film called Black Doll in existence. Do you know anything about that?

MALONEY: Yes, it has actually been published.

PHAWKER: And has anyone made a move toward making a movie?

MALONEY: I don’t know. I think it would be a really cool thing to do. Black Doll is an interesting thing, because in much of his work, a little black doll shows up. It’s one of these things where if you asked him why it was there, he would say you have to go back again and figure it out. Illustrators have these things that they often do, but with Gorey this black doll is a recurring motif that clearly has some meaning. I think a reader would do well to kind of examine that screenplay to see what they could get out of it.

PHAWKER: What kind of print run would a book like this see?

MALONEY: Several thousand. It has a fairly broad interest. I won’t give you specific numbers, but in terms of printing, we aren’t doing as many of these as a broad interest hardback nonfiction. It does have a large audience, but a specific one. The people who love Gorey are buying this. It’s not what your average reader would pick up. What I’m trying to say is that we wouldn’t be publishing it if we didn’t think we could sell copies. The interesting thing is the ways in which the Internet has changed the game in bringing a book like this back. We would have never picked it up if it hadn’t been posted online. That itself showed us that there is an audience for it, and that is one of the things the Internet can do these days for an old work. Publishing is always a guessing game, and the Internet is helping us make better guesses by shining a certain light on the dark corners of the book buying world.