TIME: Take the austere little paperbacks down from the shelf and you can hold the collected works of J.D. Salinger — one novel, three volumes of stories — in the palm of one hand. Like some of his favorite writers — like Sappho, whom we know only from ancient fragments, or the Japanese poets who crafted 17-syllable haikus — Salinger was an author whose large reputation pivots on very little. The first of his published stories that he thought were good enough to preserve between covers appeared in the New Yorker in 1948. Sixteen years later he placed one last story there and drew down the shades.From that day until his death at 91, Salinger was the hermit crab of American letters.

When he emerged, it was usually to complain that somebody was poking at his shell. Over time Salinger’s exemplary refusal of his own fame may turn out to be as important as his fiction. In the 1960s he retreated to a small house in Cornish, N.H., and rejected the idea of being a public figure. Thomas Pynchon is his obvious successor in that department. But Pynchon figured out how to turn his back on the world with a wink and a Cheshire Cat smile. Salinger did it with a scowl. Then again, he was inventing the idea, and he bent over it with an inventor’s sweaty intensity.

When he emerged, it was usually to complain that somebody was poking at his shell. Over time Salinger’s exemplary refusal of his own fame may turn out to be as important as his fiction. In the 1960s he retreated to a small house in Cornish, N.H., and rejected the idea of being a public figure. Thomas Pynchon is his obvious successor in that department. But Pynchon figured out how to turn his back on the world with a wink and a Cheshire Cat smile. Salinger did it with a scowl. Then again, he was inventing the idea, and he bent over it with an inventor’s sweaty intensity.

Salinger’s only novel, The Catcher in the Rye, was published in 1951 and gradually achieved a status that made him cringe. For decades that book was a universal rite of passage for adolescents, the manifesto of disenchanted youth. (Sometimes lethally disenchanted: After he killed John Lennon in 1980, Mark David Chapman said he had done it “to promote the reading” of Salinger’s book. Roughly a year later, when he headed out to shoot President Ronald Reagan, John Hinckley Jr. left behind a copy of the book in his hotel room.) But what matters is that even for the millions of people who weren’t crazy, Holden Caulfield, Salinger’s petulant, yearning (and arguably manic-depressive) young hero was the original angry young man. That he was also a sensitive soul in a cynic’s armor only made him more irresistible. James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway had invented disaffected young men too. But Salinger created Caulfield at the very moment that American teenage culture was being born. A whole generation of rebellious youths discharged themselves into one particular rebellious youth. MORE

HOLDEN CAUFIELD: Boy, when you’re dead, they really fix you up. I hope to hell when I do die somebody has sense enough to just dump me in the river or something. Anything except sticking me in a goddam cemetery. People coming and putting a bunch of flowers on your stomach on Sunday, and all that crap. Who wants flowers when you’re dead? Nobody.

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER: The famously reclusive author J.D. Salinger has died, but chances remain slim to none that any adaptation of his classic literary works will reach the screen or stage. With more than 65 million copies of “The Catcher in the Rye” in print, many have sought to turn Salinger’s stories into movies, Broadway shows or book sequels over the past 63 years, but the author always adamantly refused. That isn’t about to change — all because Salinger was unhappy about the one time he allowed an adaptation. Salinger, who died Wednesday at age 91 in Cornish, N.H., agreed to have one of his short stories, “Uncle Wiggily in Connecticut,” made into a movie, which was released in 1949 as “My Foolish Heart.” The film was a critical and commercial failure and apparently an affront to the author, who vowed never again to make the mistake of allowing others to interpret his vision. Ever since, numerous producers, filmmakers, authors and stage directors have sought rights to his 1945 novel, “The Catcher in the Rye,” as well as to his 1961 book “Franny and Zooey” and other stories. In 2008, the rights to his works were placed in the J.D. Salinger Literary Trust, of which the author was sole trustee. Phyllis Westberg, who was Salinger’s agent at Harold Ober Associates in New York, declined Thursday to say who the trustees are now that the author is dead — but she was clear that nothing has changed in terms of licensing movie, TV or stage rights. “Everybody knows that he did not want it to happen, and the trust will follow that,” Westberg told THR. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: I’d rather remember Salinger (and Holden Caulfield) with the last words to “Catcher in the Rye,” words that signaled Salinger’s future seclusion even as they allowed for the joy and pain of human connection:

It’s funny. Don’t ever tell anybody anything. If you do, you start missing everybody. MORE

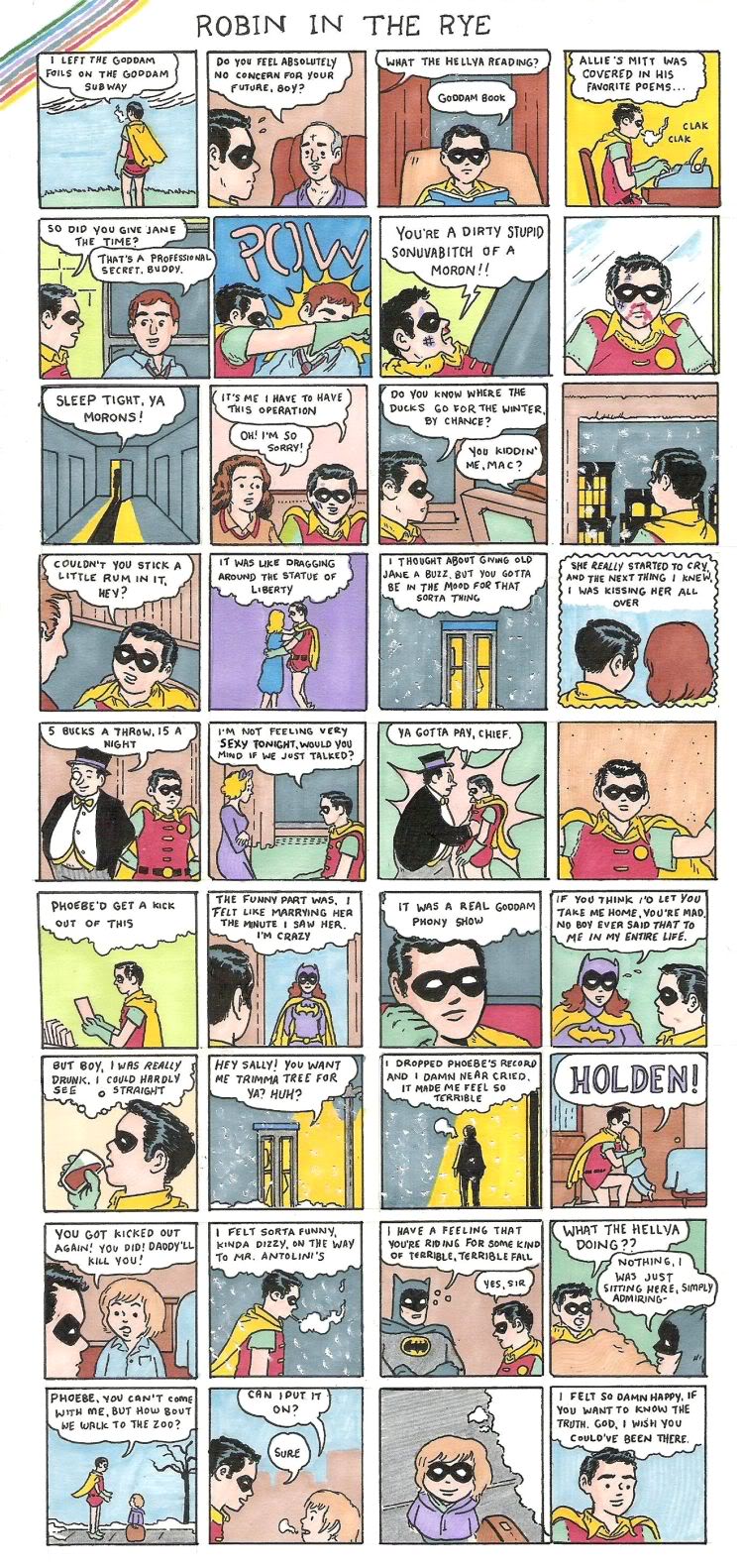

[Artwork by ANDREW LORENZI]