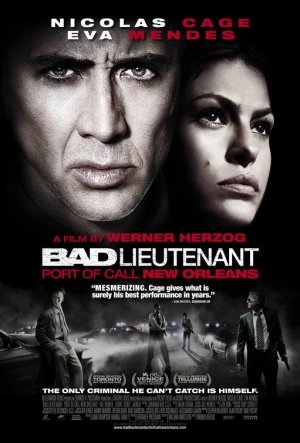

BAD LIEUTENANT: PORT OF CALL NEW ORLEANS (2009, directed by Werner Herzog, 121 minutes, U.S.)

BAD LIEUTENANT: PORT OF CALL NEW ORLEANS (2009, directed by Werner Herzog, 121 minutes, U.S.)

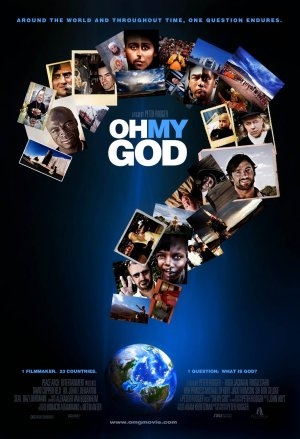

OH MY GOD (2009, directed by Paul Rodger, 93 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

If you think the Batman series has turned dark, you won’t believe the latest film franchise. Bad Lieutenant, the 1992 film gave Harvey Keitel a chance to wail naked as the drug-addicted criminal cop has returned, re-imagined by its producer Edward Pressman as a showcase for the long-dismantled weirdness of Nicholas Cage. Helmed by German director Werner Herzog, this new Bad Lieutenant allows the director to show another crazed character out on a limb but what is most surprising is the story’s transformation from one of sin and guilt to darkened farce.

In the original directed by Abel Ferrara, Keitel’s character (known only as “The Lieutenant”) was a scary lost soul, drowning in sex and drugs and secretly hoping for his soul (and the NY Mets’) redemption. Keitel’s character was frightening and dangerous, we related to him the way we might a wounded shark, with a mix of pity and fear. Herzog’s Lieutenant is set in post-Katrina New Orleans, a place he sees as being Godless and irredeemable, like the first American post-apocalypse story set in the real world.

Cage plays Terence McDonagh, a cop with a painful bad back that has left him self-medicating with what he can shake out of his suspects. Early on we see him dive into the muck to save a drowning prisoner, so we suspect there is a heart buried in there somewhere, obscured by the jittery dementia of his addiction. When he protects his prostitute girlfriend (Eva Mendes) from a violent John, Terence runs afoul of a local mobster and is forced to raise money by going into business with a local drug dealer named Big Fate (believably played by real life rapper Xzibit).

The original film has maintained its power as one of the most resonant crime films of the ’90s, disturbing and uncompromising in its examination of The Lieutenant’s depravity. Herzog’s film is not as dark, its lead character missing the sadism and predatory power of the original. What it does have is Nicholas Cage, a movie star market-tested to be irresistible on screen, and that he is. With his stiff, bad back posture and his awkward, trying-to-act-straight amphetamine energy, it’s a gas to see Cage in no condition to save the world. He shakes down club-goers for their drugs, plants evidence on suspects and makes out with their girlfriends. All this got big laughs from the audience, it’s a testament to Cage’s on-screen persona that we can so easily find ourselves rooting for a corrupt cop.

Herzog taps into his ability to give power to the absurd and he works the cop genre (with a script by longtime  TV cop show writer William Finkelstein) with an unambiguous verve that makes the film unlike anything else in the director’s filmography. It’s hard not to make comparisons to the original; I miss God hanging over the proceedings, ready to bring his wrath down on this maverick cop. Of course that was NYC in the ’90s, a much different place than modern New Orleans. Herzog brings a foreigner’s eye to modern day New Orleans, presenting his vision of a place that God and government has abandoned, a nightmare that adds the necessary weight to the giddy kick of Cage’s bad boy.

TV cop show writer William Finkelstein) with an unambiguous verve that makes the film unlike anything else in the director’s filmography. It’s hard not to make comparisons to the original; I miss God hanging over the proceedings, ready to bring his wrath down on this maverick cop. Of course that was NYC in the ’90s, a much different place than modern New Orleans. Herzog brings a foreigner’s eye to modern day New Orleans, presenting his vision of a place that God and government has abandoned, a nightmare that adds the necessary weight to the giddy kick of Cage’s bad boy.

– – – – – – – – – – –

God is still haunting locals theaters though, most visibly in the debut documentary from director Paul Rodger titled Oh My God. Rodger had a simple premise, wander the globe, thrust the camera in people’s faces and ask “What is God?” He never gets far beyond this though, he doesn’t find a way to sort through or expand on these ideas, instead the movie becomes an endless parade of faces giving short vague answers (has “God is Love” ever sounded more trite?) while its slick world beat gumbo rock surges uninterrupted for ninety three minutes. He checks in with many of the world’s greatest religious thinkers, namely Hugh Jackman, Ringo Starr, Seal and magician David Copperfield. Okay, assorted monks and priests get their say too but by editing their comments down to a few short sentences, Rodger gives the film the heft of bumper sticker spirituality. Oh My God wants to illuminate the Big Ideas, but its shallow premise emits the beam of a keychain flashlight.