BY PAUL MAHER JR. When I was just a kid in Lowell, Massachusetts during the 1970s, I went into a Pawtucketville pet store and saw this 10-gallon fish tank set among cages of rabbits and guinea pigs. Scurrying through the wood shavings were over five dozen albino feeder mice fighting for space. Some of them were running relentlessly on a squeaking tin wheel. Others clung to a dripping water bottle trying to escape the madness below. Their little pink tales draped across an encrusted food bowl spoiled by urine and feces. Most glaringly, in the corner of the tank, three or four of them were dragging around a headless cousin of theirs, a doomed albino stained red on its stark white fur. Beneath the shavings there lay another, gutted out, thoroughly cannibalized. Even mice, it seemed, could not handle crowded, claustrophobic conditions before they inevitably turned on each other. This microcosmic rendition of dysfunctional social conditioning (think of the same scenario in ghetto conditions, the mental unrest it might cause should one be forced to endure it for too long) can be considered the literal version of Stephen King’s Niagara of a novel, Under the Dome (Scribner).

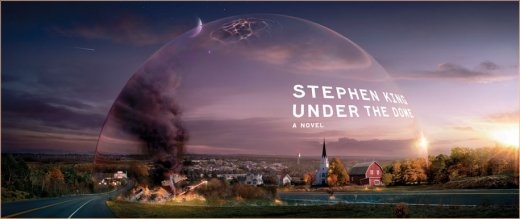

This book, a relic of King’s archival trunk, was rewritten via King’s typical manic, disciplined work ethic in the late 70s and early 80s, abandoned again, and newly-resuscitated in 2008. All but the first chapter was rewritten to fruition thus bringing King’s typical reliance on current fads and pop culture (and it is the first chapter, “The Airplane and the Woodchuck,” that perhaps has the most arresting imagery of the whole book!) up to date. Under the Dome literally places the residents of Chester’s Mill, Maine under a spherical dome that appears out of nowhere without explanation. People become like those mice in the fish tank. They can’t get out, no one can get in. They are trapped within and under the pretenses of King’s authorial intentions, are weighed down by an allegorical slugfest. Inevitably, bloodshed ensues and the death count escalates. It is a good premise for a novel, and it is likely that nobody but Stephen King can make it work and in some ways he does, but . . .

When I was young, around the time of that fish tank of flesh-eating mice in Lowell, I avidly read King’s books,  those that die-hard fans consider his best: The Stand, Night Shift, The Shining, Carrie . . . a fixation that began one fall, at the Westford Flea Market. There were hundreds of tables of goods with numerous open boxes of paperback books available for under a buck. Out of them I bought my first Stephen King book, Salems Lot. I read it and, of course, there were scenes within that chilled my soul. It wasn’t the overall Dracula-spin-off of the book that got to me, but the individual power of scenes: the baby in the high chair plopping pudding out of its mouth, a floating Danny Glick tapping at the window to be let in, the dirty old man lusting after Ruthie Crockett, the corpse of Hubie Marsten hanging from a tree. Remember, this is New England, where I live, it’s fall, the trees are bare and the crows silhouette the stark-dusk trees. The title of Salems Lot evokes that of Salem, Massachusetts, a middle school mainstay that time of year for field trips, a town notorious for its witch trials that continues to echo its violent legacy through every square inch of the state. It was in the spirit of that vibe that I came to appreciate Stephen King. Though Salems Lot had more to do with vampires than witches, its stark black cover on the paperback edition with its one drop of red blood inking from the corner of a child’s mouth did the job for me. Stephen King was America’s new literary bad-ass. Having one of his tattered paperbacks in hand in high school almost guaranteed that one of those hot girls that normally wouldn’t give you the time of day (and for some reason, was always the stoner-type), would now stop and talk about that book you were holding (or better yet, she would ask you to loan it to her, and in all likelihood she would never return it and you wouldn’t care, because now you had that link, however desperate it may be). King was also the antidote toward fending off those more-literate-than-thou honors-class geeks bogged down by the fantasy of orcs, hobbits and wizards. It was the 1970s version of Dungeons and Dragons bolstered by the shitty animated version of The Hobbit that had been released in 1977 thereby making Tolkein the Harry Potter and Twilight of its day (and I didn’t like the books then, but can appreciate them now).

those that die-hard fans consider his best: The Stand, Night Shift, The Shining, Carrie . . . a fixation that began one fall, at the Westford Flea Market. There were hundreds of tables of goods with numerous open boxes of paperback books available for under a buck. Out of them I bought my first Stephen King book, Salems Lot. I read it and, of course, there were scenes within that chilled my soul. It wasn’t the overall Dracula-spin-off of the book that got to me, but the individual power of scenes: the baby in the high chair plopping pudding out of its mouth, a floating Danny Glick tapping at the window to be let in, the dirty old man lusting after Ruthie Crockett, the corpse of Hubie Marsten hanging from a tree. Remember, this is New England, where I live, it’s fall, the trees are bare and the crows silhouette the stark-dusk trees. The title of Salems Lot evokes that of Salem, Massachusetts, a middle school mainstay that time of year for field trips, a town notorious for its witch trials that continues to echo its violent legacy through every square inch of the state. It was in the spirit of that vibe that I came to appreciate Stephen King. Though Salems Lot had more to do with vampires than witches, its stark black cover on the paperback edition with its one drop of red blood inking from the corner of a child’s mouth did the job for me. Stephen King was America’s new literary bad-ass. Having one of his tattered paperbacks in hand in high school almost guaranteed that one of those hot girls that normally wouldn’t give you the time of day (and for some reason, was always the stoner-type), would now stop and talk about that book you were holding (or better yet, she would ask you to loan it to her, and in all likelihood she would never return it and you wouldn’t care, because now you had that link, however desperate it may be). King was also the antidote toward fending off those more-literate-than-thou honors-class geeks bogged down by the fantasy of orcs, hobbits and wizards. It was the 1970s version of Dungeons and Dragons bolstered by the shitty animated version of The Hobbit that had been released in 1977 thereby making Tolkein the Harry Potter and Twilight of its day (and I didn’t like the books then, but can appreciate them now).

Over the years King’s output increased. I bought each and every book, my stint in the navy from 1982 through 1987, gave me plenty of time to read them all (I even bought the first edition of The Dark Tower in a little comic book shop in San Diego, California, and disappointed with it, sold it off, bad move, it sells for up to a grand these days). However, after reading them all, I wasn’t getting the same satisfaction I used to have. That alluring magic that kept me up until dawn, homework be damned, was the ultimate stamp of the captivation of a Stephen King book. I remember the short story collection, Night Shift, and this scenario: “Okay, now just one more story and I’m off to bed.” I’d finish that story and then, “okay, now one more.” This continued until the dawn, story after story, with the back of your mind still expecting Danny Glick to tap your window, or to hear that slow shuffling corpse rising from the hotel bathtub of The Shining. King’s feral imagination plagued our own, and we only had to thank him for it, even if we didn’t get any sleep and we got a zero for not doing our homework.

King also had a handle on the motives of adolescence: there was the school bully asshole, the jocks, and those floundering about trying to adjust, like Arnie from Christine (1983), rising from unpopular zit-faced geek to the class debonair with his nice, shiny, albeit possessed car. Or that big, fat motherfucker of a novel, It (1986), that publicized itself as the mighty ejaculate of King’s creative mind, populated by a ragtag collective of kids calling themselves “The Losers.” In that vein, there was another element to identify with, a universe populated by people we could relate with, even though the mighty It is best appreciated, not by its sum, but its parts. Nobody really bought that a giant spider exuded all of this evil, even though it served as an embodiment of evil and that its antithesis The Turtle served as sort of a mythopoeia (which, if it had been successfully pursued, would have given the novel a firmer ground to walk on).

This brings me to Under the Dome, a monolithic capstone of a book that threatens to buckle under the weight of its 1000+ pages. This isn’t the first novel that King wrote of immense proportions. Insomnia and It are similar long novels (or the rerelease of what can be considered King’s “director’s cut” of The Stand in 1990). However, where novels like It had its individual moments to make-up for the eventual disappointing ending, Under the Dome lacks even that charm. Instead we have a constant barrage of awful dialogue that does less to further the narrative than it does to attempt to create a sense of community. There is no warmth here, no familiarity even between people that supposedly know each other. This, in many ways, is what doesn’t make the whole premise of the novel work. It is perhaps the fault I find in many of King’s books from the past two decades. Reading along, one wishes he took his time and gone deep instead of wide, more Kubrick and less Spielberg, more Dostoevsky, less Tolstoy. The usage of a small-town setting begs for intimacy, a depth of character hinting at the motives lurking beneath. Reading his books, one yearns more, and feels that there potentially could be more. He hints at this with the character of Clayton Blaisdell, Jr., the protagonist of his “trunk” novel Blaze, a struggling simpleton who misguidedly commits every parent’s nightmare. Or the sustained narrative focus of the superb The Green Mile (1996), again, for the most part kept within the confines of death row with a few sympathetic characters like accused child-killer John Coffey. King successfully creates tension and believability with novels like Dolores Caliborne and Gerald’s Game (both published in 1992) and Misery (1987) because he resorts to psychology rather than his constant crutch companion (and by his own admittance), raising the gore-factor. It becomes a crutch because it seems like he drops the gore in when he lacks a solution to a more carefully-considered conflict. King’s mastery of plot points in his longer, denser novels always threatens to buckle under the problem of how to create a satisfying ending. Regrettably, a fiery explosion becomes a favorite of his (The Stand, Firestarter The Shining, Salems Lot, Pet Sematary, Needful Things) or that of a power-hungry character threatening social collapse under dire circumstances (Under the Dome, Bag of Bones, The Stand, The Mist). They become, in a way, clichés committed by a brand name.

This brings me to Under the Dome, a monolithic capstone of a book that threatens to buckle under the weight of its 1000+ pages. This isn’t the first novel that King wrote of immense proportions. Insomnia and It are similar long novels (or the rerelease of what can be considered King’s “director’s cut” of The Stand in 1990). However, where novels like It had its individual moments to make-up for the eventual disappointing ending, Under the Dome lacks even that charm. Instead we have a constant barrage of awful dialogue that does less to further the narrative than it does to attempt to create a sense of community. There is no warmth here, no familiarity even between people that supposedly know each other. This, in many ways, is what doesn’t make the whole premise of the novel work. It is perhaps the fault I find in many of King’s books from the past two decades. Reading along, one wishes he took his time and gone deep instead of wide, more Kubrick and less Spielberg, more Dostoevsky, less Tolstoy. The usage of a small-town setting begs for intimacy, a depth of character hinting at the motives lurking beneath. Reading his books, one yearns more, and feels that there potentially could be more. He hints at this with the character of Clayton Blaisdell, Jr., the protagonist of his “trunk” novel Blaze, a struggling simpleton who misguidedly commits every parent’s nightmare. Or the sustained narrative focus of the superb The Green Mile (1996), again, for the most part kept within the confines of death row with a few sympathetic characters like accused child-killer John Coffey. King successfully creates tension and believability with novels like Dolores Caliborne and Gerald’s Game (both published in 1992) and Misery (1987) because he resorts to psychology rather than his constant crutch companion (and by his own admittance), raising the gore-factor. It becomes a crutch because it seems like he drops the gore in when he lacks a solution to a more carefully-considered conflict. King’s mastery of plot points in his longer, denser novels always threatens to buckle under the problem of how to create a satisfying ending. Regrettably, a fiery explosion becomes a favorite of his (The Stand, Firestarter The Shining, Salems Lot, Pet Sematary, Needful Things) or that of a power-hungry character threatening social collapse under dire circumstances (Under the Dome, Bag of Bones, The Stand, The Mist). They become, in a way, clichés committed by a brand name.

Yet, God bless him, one cannot begrudge King, who has the fiercest literary work ethic in America, for being productive. King works out of his own will, probably no longer concerned with earning, than he is of creating. His position is the envy of countless writers everywhere, whether one likes him or not. After being sideswiped by a car in the summer of 1999, King was certain he would not be able to write again. When he did, he came back fiercely committed to his craft. A spew of his works were published, bringing with them a new respectability for King in the 21st century. He finished his long wished for Dark Tower series, switched publishers and seemed bent on redefining himself as an author. Yet this was without complaint. Stanley Kubrick felt that King wasn’t “literary” enough, and in some ways he isn’t and in other ways one can see how he clearly could be. By dropping some of his shallower tangents of horror writing, or to write horror without making it seem so much like horror (for Bram Stoker wasn’t trying to write a “horror” novel, Dracula threaded throughout with myth and folklore), it wouldn’t be so hard to envision King’s version of Faulkner’s masterful Light in August arising out of some obscure Maine hamlet. Somewhere lurking under the dome of Chester Mills, Maine there lies a version of a white-trash Snopes, he just doesn’t show himself in Under the Dome. One wishes that King would follow Faulkner’s initiative when he decided to close the door on the world and write The Sound and the Fury. If only he would stop giving a fuck-all about his fans and critics and their expectations and dredge from the shit-storm apocalypse of current-day America, a novel that bears and improves upon repeated readings, one that grows with maturity, and endures the test of time (which means leave out the brand names, celebrities and dated phrases).

King was denounced by many, including book critic and Yale’s academic drone, Harold Bloom (who could forget Bloom’s tirade in the Los Angeles Times: “ I read a lavish, loving review of Harry Potter by the same Stephen King. He wrote something to the effect of, “If these kids are reading Harry Potter at 11 or 12, then when they get older they will go on to read Stephen King.” And he was quite right. He was not being ironic. When you read “Harry Potter” you are, in fact, trained to read Stephen King.”), for receiving the Medal of Distinguished Contribution to American Letters by the American Book Award in 2003. He deserves the lifetime achievement award, not only for his enormous body of work, but because he is able to bring relief from the drudgeries of a 40-hour work week, a stay in a hospital bed or a day at the beach. King has become the Edgar Allan Poe for the working class, and most that can identify with King’s vast cornucopia of characters are themselves plucked from the underbelly of America. However, I still feel that there is more to King, and I eagerly await the day when he yanks back the thick layers of his readers’ expectations, and delves deep into his writing like Melville (or, again, Dostoevsky). The end-all, be-all of his novels will conjure the mad horror of America using the sparse settings of Malick’s Badlands, hopefully evoking a world of chaos, more “sound and fury” than, like Under the Dome, “signifying nothing.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Paul Maher Jr. is the writer of two biographies of Jack Kerouac, the editor of two volumes of interviews with Kerouac and Miles Davis and another with Tom Waits due out in fall 2010. He is also a photographer. Maher is working on two screenplays about the captivity of Mary Rowlandson and the prison years of Dostoevsky.

[Stephen King illustration by QUICK HONEY]