[Photo by THE BMAG]

FOX43: Emergency Management Agency officials reported low levels of radiation were measured on monitors at Three Mile Island Reactor Unit 1 at about 4 p.m. on Saturday, prompting about 150 workers to be removed from the reactor building. According to Exelon, the energy company operating TMI, all the workers were checked for exposure, but none of them approached or exceeded any exposure limits. An official with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission said about 20 workers were exposed to levels of radiation so low they did not fall under NRC limits. Exelon spokesman Ralph DeSantis said there was no contamination identified outside the reactor building and the public was never in danger. Dauphin County and state EMA officials did not  learn of the incident until Middletown Mayor Robert Reid contacted the county’s 911 Center at 9:30 p.m., 5 1/2 hours after the radiation release. MORE

learn of the incident until Middletown Mayor Robert Reid contacted the county’s 911 Center at 9:30 p.m., 5 1/2 hours after the radiation release. MORE

CNN: Tests showed the contamination in Saturday’s incident was confined to the building itself, and none was found outside, Exelon said. There was no threat to public health and safety, but the workers were sent home because they could not continue until the area was cleaned, Bill Noll, Exelon vice president, said in the Saturday statement. One worker was found to have received 16 millirem of exposure, and others received lower levels of contamination. The annual occupational dose limit for workers at Exelon plants is 2,000 millirem, the statement said. MORE

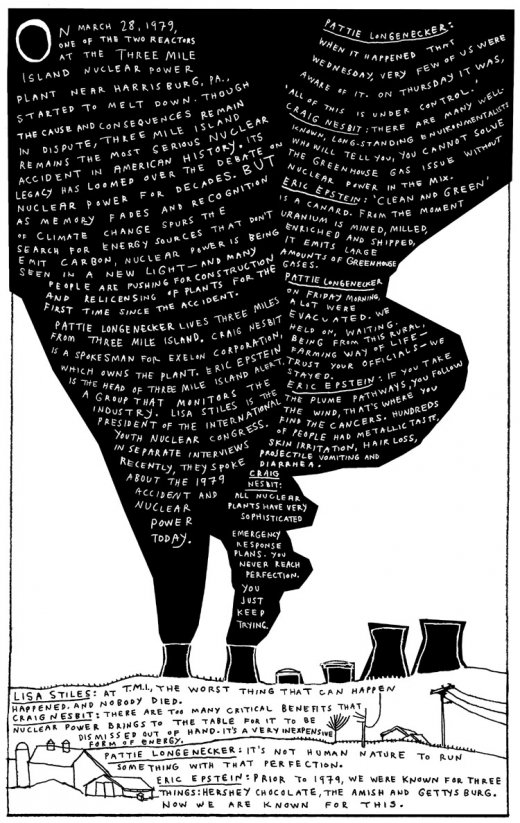

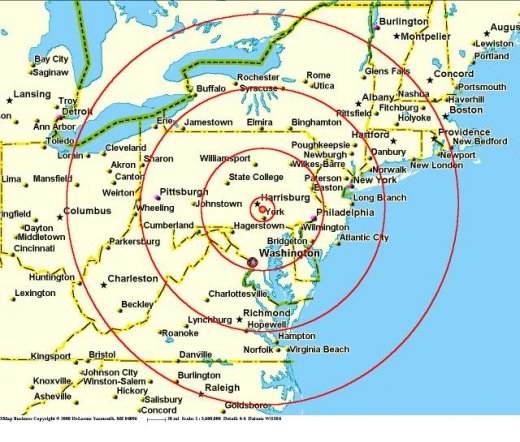

PREVIOUSLY: Thirty years ago, half the core of a reactor at the Three Mile Island nuclear complex melted down, but government officials and the utility running the place didn’t know that. And they wouldn’t know for six more years. In fact, as the crisis extended from its start on March 28, 1979, the amount of information available about the nature of the accident remained slim. Key pieces of data were missing. Nobody knew exactly what was happening inside the containment vessel and, more importantly, what was coming out of it. The sensors designed to measure radioactive release were overwhelmed. “It was a bit of an engineering nightmare because they didn’t understand how the plant was functioning at that time,” Sullivan said. At first, utility and government officials contended that only 180 or maybe 360 of the 36,000 containment rods had  melted. Those numbers were up to 9,000 rods shortly after the accident, but the cooler heads prevailed a little too well in this case. For a while in the early 1980s, nuclear power industry officials maintained that no melting had occurred — and that was a major reason for claiming the coverage of the affair was overblown.“Little, if any, fuel melting occurred, even though the reactor core was uncovered. The safety systems functioned reliably,” said D.B. Trauger, a nuclear engineer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, at an engineering conference eight months after the accident. “Based on the conservative licensing analyses, the core was subjected to conditions that would have produced a total melt…. This accident has revealed that reactors are orders of magnitude safer than previously assumed.” In fact, it took excavation of the containment vessel in the mid-’80s to glimpse the true extent of the damage. What workers found was shocking. The Washington Post’s Three Mile Island timeline summarized the new severity estimates, “Core temperatures reached 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit; as much as 50 percent of the fuel melted.” Today, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission recognizes that half the core melted. MORE

melted. Those numbers were up to 9,000 rods shortly after the accident, but the cooler heads prevailed a little too well in this case. For a while in the early 1980s, nuclear power industry officials maintained that no melting had occurred — and that was a major reason for claiming the coverage of the affair was overblown.“Little, if any, fuel melting occurred, even though the reactor core was uncovered. The safety systems functioned reliably,” said D.B. Trauger, a nuclear engineer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, at an engineering conference eight months after the accident. “Based on the conservative licensing analyses, the core was subjected to conditions that would have produced a total melt…. This accident has revealed that reactors are orders of magnitude safer than previously assumed.” In fact, it took excavation of the containment vessel in the mid-’80s to glimpse the true extent of the damage. What workers found was shocking. The Washington Post’s Three Mile Island timeline summarized the new severity estimates, “Core temperatures reached 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit; as much as 50 percent of the fuel melted.” Today, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission recognizes that half the core melted. MORE

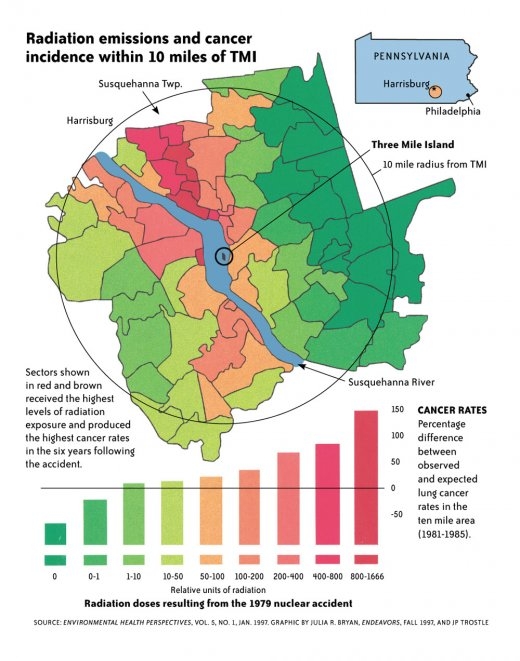

RELATED: But the official story that there were no health impacts from the disaster doesn’t jibe with the experiences of people living near TMI. On the contrary, their stories suggest that area residents actually suffered exposure to levels of radiation high enough to cause acute effects—far more than the industry and the  government has acknowledged. Some of their disturbing experiences were collected in the book Three Mile Island: The People’s Testament, which is based on interviews with 250 area residents done between 1979 and 1988 by Katagiri Mitsuru and Aileen M. Smith.

government has acknowledged. Some of their disturbing experiences were collected in the book Three Mile Island: The People’s Testament, which is based on interviews with 250 area residents done between 1979 and 1988 by Katagiri Mitsuru and Aileen M. Smith.

It includes the story of Jean Trimmer, a farmer who lived in Lisburn, Pa., about 10 miles west of TMI. On the evening of March 30, 1979, Trimmer stepped outside on her front porch to fetch her cat when she was hit with a blast of heat and rain. Soon after, her skin became red and itchy as if badly sunburned, a condition known as erythema. About three weeks later, her hair turned white and began falling out. Not long after, she reported, her left kidney “just dried up and disappeared”—an occurrence so strange that her case was presented to a symposium of doctors at the nearby Hershey Medical Center. All of those symptoms are consistent with high-dose radiation exposure.

There was also Bill Peters, an auto-body shop owner and a former justice of the peace who lived just a few miles west of the plant in Etters, Pa. The day after the disaster, he and his son, who like most area residents were unaware of what was unfolding nearby, were working in their garage with the doors open when they  developed what they first thought was a bad sunburn. They also experienced burning in their throats and tasted what seemed to be metal in the air. That same metallic taste was reported by many local residents and is another symptom of radiation exposure, commonly reported in cancer patients receiving radiation therapy.

developed what they first thought was a bad sunburn. They also experienced burning in their throats and tasted what seemed to be metal in the air. That same metallic taste was reported by many local residents and is another symptom of radiation exposure, commonly reported in cancer patients receiving radiation therapy.

Peters soon developed diarrhea and nausea, blisters on his lips and inside his nose, and a burning feeling in his chest. Not long after, he had surgery for a damaged heart valve. When his family evacuated the area a few days later, they left their 4-year-old German shepherd in their garage with 200 pounds of dog chow, 50 gallons of water and a mattress. When they returned a week later, they found the dog dead on the mattress, his eyes burnt completely white. His food was untouched, and he had vomited water all over the garage. They also found four of their five cats dead—their eyes also burnt white—and one alive but blinded. Peters later found scores of wild bird carcasses scattered over their property. MORE