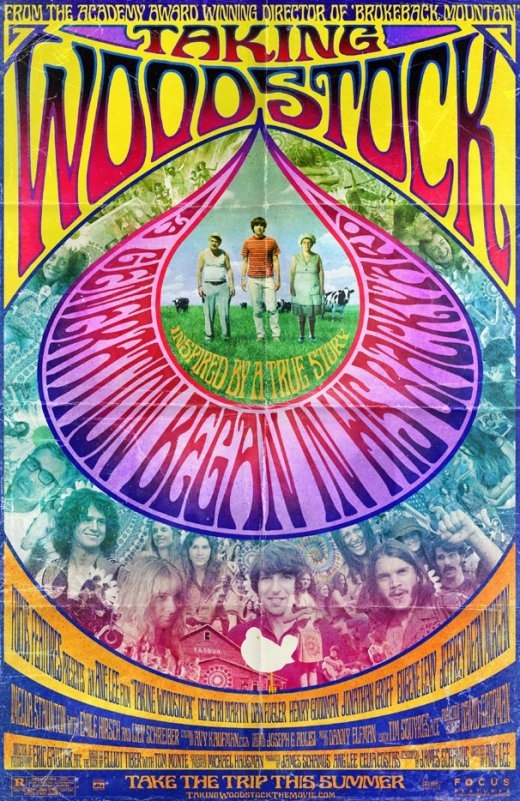

TAKING WOODSTOCK (2009, directed by Ang Lee, 110 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

The legacy of the Woodstock concert continues to be a point of contention 40 years later. The counter-cultural revolution embodied by the Three Days of Peace & Music has become conservative shorthand for “the excesses of the 60s” (a phrase even Obama has been known to use), a point-of-view perhaps best exemplified cinematically by the film Forrest Gump, where all the characters who seek self-knowledge in the sixties and seventies are struck down by insanity and disease. The new film by director Ang Lee attempts to reclaim the meaning of Woodstock and celebrate the loosening of societal mores that the era brought about. Telling the story through the eyes of Elliot Teichberg, the head of the Bethel Chamber of Commerce who originally granted the permit for the festival, director Lee seeks to get to the meaning of Woodstock without recreating the concert. It’s winning strategy, posing to the idea that the ephemeral creation of a counterculture city in the middle of the Catskills was more ground-breaking than the concert itself.

Elliot is in his mid-thirties (although as played by actor/comedian Demetri Martin, you would guess he’s a decade younger), a closeted gay man who tasted freedom while briefly living in New York City but has had to give it up to take care of his Jewish immigrant parents’ dilapidated motel in the Catskills. With the family business on its way to foreclosure, Elliot sees the opportunity to save his parent’s business by granting a permit to the Woodstock Ventures. With the festival scheduled to begin in mere weeks, Dimitri contacts the promoters and before you know it, Woodstock’s hippie angel, promoter Michale Lang, has descended from the heavens via helicopter with a large bag of cash. From that moment on Elliot and the irate citizens of Bethel, New York are forced to deal with the crush of a half-million long-haired freaky young people descending on their county like a touring cast of Hair.

Adapted from Elliot Tiber’s memoir by Lee’s longtime collaborator James Schamus, Taking Woodstock is told with the type of literary attention to detail Ang Lee brings to all his work (a distinction somewhat obscured by Taking Woodstock‘s superficial trailer). Lee is just as thoughtful in recreating un-hip small town life as he is at presenting the wild fashions of the hippie tribe. Too many recreations of the late ’60s center themselves in the world of the young counterculture; by setting this story in small town America, Lee gives us the context to see what the counterculture was rebelling against, as well as its allure for people ambivalent about embracing its lifestyle.

Once the thongs arrive the chaos descends on the film itself; multiple characters are introduced quickly, the most memorable being Liev Schriber’s Vilma, a cross-dressing former Marine whose outrageous appearance gives Eliot added confidence in being true to his own self. Moving little scenes pile up, including when Richie Haven’s “Freedom” comes wafting across the lake behind the motel, leading Eliot’s father (Henry Goodman) to quietly encourage him to go to the concert. He does attend, having perhaps a too-perfect Woodstock experience, beating the traffic with a police escort, sliding in the mud and having an acid-fueled bisexual group sex romp in the back of a van while listening to Love’s “Forever Changes.”

At times, Lee uneasily walks the line between commercial and art house filmmaking. He leaves the question of Elliot’s parents’ knowledge of his homosexuality realistically vague yet he can’t resist hammering home the emotional catharsis, as when his parents mistakenly chow down on Hash brownies and lose their frustrating inhibitions while dancing in the rain. Somehow Demetri Martin, in his first major acting role, ties the whole thing together. Famous for his deadpan stand-up, Martin’s anti-movie star looks and un-actorly restraint ground the film in a reality that makes the circus around him more believable.

Lee’s Taking Woodstock comes down unapologetically in favor of the politics espoused in the late sixties (it even works its anti-war element in with a not-quite-believable Emile Hirsch as the an old high school friend shell-shocked from serving in ‘Nam) while being honest enough to critique them. One of the film’s subtler moments is when Elliot is discussing the spectacle with a young hippie girl. She starts to critique the crowd in spiritual terms, then becomes embarrassed by the weight of her words. Elliot tries to encourage her but there’s a beautifully intimate discomfort that hangs between them, part politics/part morality that captures the insecurity of the times in wonderfully eloquent manner.

Despite its occasional missteps, Taking Woodstock has enough beautifully underplayed moments to make it among the most honestly open-hearted films of the year, containing particularly strong work from Eugene Levy as business-savvy farmer Max Yasgur and Jonathan Groff as Michael Lang, the semi-preposterous Uber hippie who seems to believe his own bullshit with such conviction as to make the improbable near-disaster actually come off (many critics are raving about Imelda Staunton’s Mother Teichberg, for me the part was too shrilly-written to do justice). At its core Taking Woodstock is an exceptionally well-observed story of a father and a son, coming to respect each other when the son inadvertently brings a maelstrom down upon them. That their story is not swamped but only deepened by having a moment as grand as Woodstock as its backdrop, shows you just how adept Ang Lee has become at his craft.