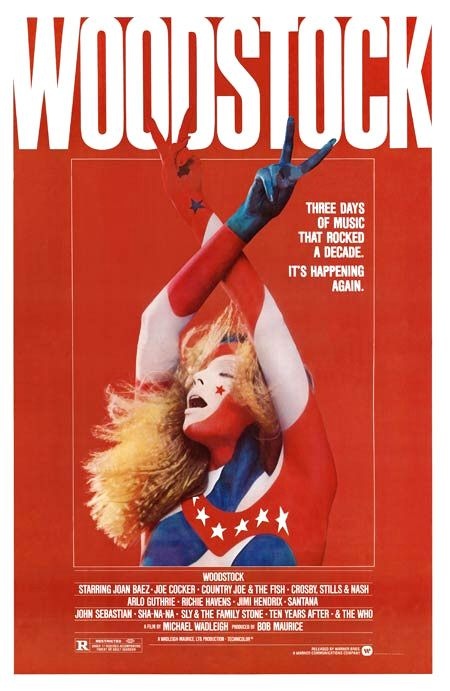

WOODSTOCK (Directed by Michael Wadleigh, 184 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

For the fortieth anniversary Warner Brothers has whipped up quite a promotional frenzy around the most legendary festival of the twentieth century, Woodstock. Half a million people are estimated to have attended it, the triple record set went to number one on the Billboard charts in 1970, yet what most people are really discussing when they mention Woodstock is their memories of the Oscar–winning documentary of the event, directed by Michael Wadleigh. The film was a phenomenon of its time, bringing a piece of the counter-culture to the nooks and crannies of the country whom hadn’t experienced it, and raking in fifty million dollars to become the largest grossing documentary of its time.

A cornerstone work of the cinema verite movement, Woodstock the film has become a victim of Warner Brothers’ greed, with its multiple re-packagings tearing apart Wadleigh’s careful calibrations in order to jam in more performances (despite its “Director’s Cut” label Wadleigh has gone on record expressing his dislike for the currently available version on DVD). At its original three hour and four minute length, the film Woodstock was just long enough to capture what Jerry Garcia describes on camera as the “Epical, Biblical” scope of the event, but at its current three hour and forty-eight minute length the balance between the music and the sociological and political asides spill over into gargantuan excess. It’s a shame that the edit that won the film its Oscar in 1971 has never been released on DVD

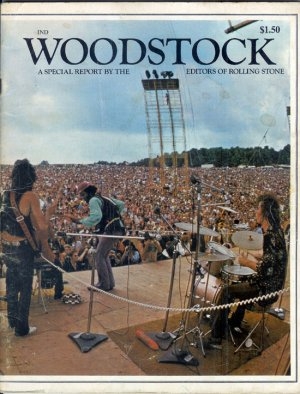

Wadleigh was twenty six when the producers of the Woodstock festival approached him with the idea of the film. At the time all they had was the iconic  logo of the bird perched on the guitar and the idea of the festival as a modern Canterbury Tale, with the audience traveling into the cathedral of nature. A former medical student, Wadleigh had made a few short films, one on the American Communist Party’s frequent Presidential candidate Gus Hall as well as some unreleased music footage which featured Aretha Franklin captured live with four cameras, in the same split-screen manner later used in the Woodstock film. Seeing the footage of The Queen of Soul the producers were sold: “You’ve got the gig!” they told him. When Wadleigh asked what it paid he was told that they had no money, he would have to finance the film on his own. Turns out that many other major documentarians turned them down on this “deal.” Thankfully, Wadleigh accepted. Using $50,000 dollars from his own bank account, Wadleigh hired one hundred crew members, using fifteen 16mm cameras to catch the action, with Wadleigh stationed front and center at the stage to document the music.

logo of the bird perched on the guitar and the idea of the festival as a modern Canterbury Tale, with the audience traveling into the cathedral of nature. A former medical student, Wadleigh had made a few short films, one on the American Communist Party’s frequent Presidential candidate Gus Hall as well as some unreleased music footage which featured Aretha Franklin captured live with four cameras, in the same split-screen manner later used in the Woodstock film. Seeing the footage of The Queen of Soul the producers were sold: “You’ve got the gig!” they told him. When Wadleigh asked what it paid he was told that they had no money, he would have to finance the film on his own. Turns out that many other major documentarians turned them down on this “deal.” Thankfully, Wadleigh accepted. Using $50,000 dollars from his own bank account, Wadleigh hired one hundred crew members, using fifteen 16mm cameras to catch the action, with Wadleigh stationed front and center at the stage to document the music.

Wadleigh went into the project hoping to give the counterculture a fair airing of their grievances. Remember, this is the summer after the anarchy of the ’68 Chicago Democratic convention, and the chaos there was as often laid at the feet of the counterculture protesters as it was at Mayor Daley’s police. Every week Jack Webb’s Sgt. Friday would invent some irresponsible hippie to lecture on prime time TV and depictions of squirrelly long-hairs detached from reality were the brunt of humor and disdain everywhere in the mass media. Although far more sympathetic to the hippies in attendance than most Hollywood films of its era, Wadleigh’s film questions his generation’s values and naivete even as it acts as a counterculture propaganda piece. [CONT. AFTER THE JUMP]

***

Phawker film critic Dan Busirk speaks before a Wednesday Night screening of the film Woodstock at 7pm at The Princeton Public Library, 65 Witherspoon St., Princeton, NJ. Info at http://www.princeton.lib.nj.us/

***

Woodstock’s idealism that is stressed in the film’s first hour, with the rolling green hills of Yasgur’s Farm serenaded by the unseen Canned Heat singing “Goin’ Up the Country,” a song that extols the sort of Eden to which the hippies seek to return, a place to escape the violence and soothe the wounded idealism felt by a generation that just lived through the violence of inner city riots and the assassination of RFK and MLK:

“I’m going where the water tastes like wine

We can jump in the water, stay drunk all the time

I’m gonna leave this city, got to get away

All this fussing and fighting, man, you know I sure can’t stay”

As the smiling long-hairs begin to arrive we see numerous interviews with locals, awkwardly recounting their pleasant interactions with the gathering freaks. A tavern owner shows surprise: “I got no kicks, it was ‘Sir this’ and ‘Sir that.'” One smiling chief of police says “they can’t be questioned as good Americans.” Nuns flash peace signs, everyone is cheerful, young and beautiful and cops and freaks seem to have forged a friendly alliance. San Francisco rock promoter Bill Graham is the first person we see who realizes the young promoters (all of them in their twenties) are in over their heads. He’s spotted talking to festival organizer Artie Kornfeld and shaking his head, saying “you’ve got to have some control,” offering an analogy of South American ants being stopped by flaming ditches. “I’m not saying you should set fires but you’ve got to do something,” As the hordes of humanity engulf the site, promoters Michael Lang and Kornfeld are quickly resigned to the fact that they’ve lost control of their event. With the fences cut down (reportedly by the NYC anarchist group UAW/MF, an acronym for “Up Against the Wall Mother Fuckers”) the festival is soon announced on stage as a free show and everyone holds their breath, hoping that pandemonium doesn’t ensue.

Martin Scorsese remembers the threat of disaster that was lurking. He was an assistant director on the film (along with his longtime editor Thelma Schoonmaker), suspended on a platform over the stage, nervously directing the cameramen towards action they couldn’t see through their viewfinders. Years later he recalled thinking: “What if something goes crazy? What if one of the drugs doesn’t work, or works too well, and they decide to charge the stage? Today, people sentimentalize the Woodstock spirit, but I do think it contained the never-fused elements of something more threatening.” He only had to wait four months to see Altamont.

Between sets from Crosby, Stills & Nash (Neil Young performed with them but demanded that the film crew not film his segment), Sly and The Family Stone (who managed to whip the crowd into a frenzy with a set that started at 3am) and The Who (who were correct in thinking their set was pretty ragged) Wadleigh mixes the skinny dipping and good vibes with the reports of bad acid, the angry neighboring farmers whose fields were trampled (farmer: “You want me to explain it in plain English? A shitty mess”) and news of a couple of on-site deaths (one by overdose — “I Want To Take You Higher” indeed — another when a sleeping camper was squashed by a tractor).

Between sets from Crosby, Stills & Nash (Neil Young performed with them but demanded that the film crew not film his segment), Sly and The Family Stone (who managed to whip the crowd into a frenzy with a set that started at 3am) and The Who (who were correct in thinking their set was pretty ragged) Wadleigh mixes the skinny dipping and good vibes with the reports of bad acid, the angry neighboring farmers whose fields were trampled (farmer: “You want me to explain it in plain English? A shitty mess”) and news of a couple of on-site deaths (one by overdose — “I Want To Take You Higher” indeed — another when a sleeping camper was squashed by a tractor).

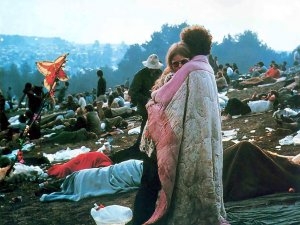

Many of the musical performances Wadleigh chooses highlight the righteous politics still brewing (Joan Baez’s union tune “Joe Hill,” Country Joe’s “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ To Die” and Richie Haven’s improvised “Freedom”) and like a good Leftist he even underlines some of the thankless labor that kept this precarious event afloat in the famous interview with the Port-O-San cleaner. But the longest and most insightful interview is with an unnamed young couple as they’re on their way to the festival. In their youthful but weary manner they detail their lack of communication with their parents (“My mother’s sure I’m going to Hell”), their disillusionment with the drug culture (“it seems like it’s almost contrived”) and most importantly their lack of interest in politics. “I’m a human being, and that all I want to be. I don’t want to have a mass change, mass change only brings about mass insanity. I just want to be myself and find a place where I can find a balance within myself.”

Woodstock is a celebration, the type of celebration that comes at the end of a long road. That weary young couple have resigned themselves to Nixon, have given up on saving the world or stopping the war; they’re instead going to head into themselves to look for peace. Crosby, Stills Nash and Young, who were basically born at this festival, signal the end of political rock (give or take an “Ohio” or two) and inaugurating the Me Generation and its self-involved singer songwriters. By the time Hendrix finishes his searing, violent take on the National Anthem we see the rolling hills of Yasgur’s Farm has been turned into a muddy, debris-strewn battlefield, with garbage fires being built to pollute this former Eden, its long-haired angels expelled by God.

Wadleigh captures it all, his omnipresent cameras often seeing four scenes at once. What did he get for this brilliant debut, which continues to make a fortune for Warner Communications? Very little. Heading out to Hollywood, he found they were leery of his political ideas, quoting Jack Warner himself, “If you want to send a message, call Western Union.” Wadleigh made one more film a decade later, Wolfen, about Native American shape shifters who become terrorists to avenge the white man’s theft of New York City, famously sold for a handful of beads. The studio took that film away from Wadleigh and re-cut it. Now forty years later they’re congratulating themselves for making Woodstock, knowing full well they wouldn’t dream of making so audacious a social document again.

Phawker film critic Dan Busirk speaks before a Wednesday Night screening of the film Woodstock at 7pm at The Princeton Public Library, 65 Witherspoon St., Princeton, NJ. Info at http://www.princeton.lib.nj.us/