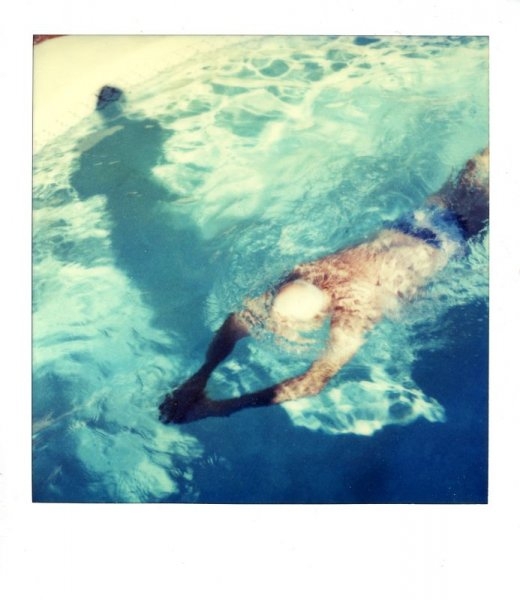

[Photo by fotonomous]

BY JEFF DEENEY Philadelphians know all too well that thinly-veiled racial tensions have been festering in the Greater Northeast long before the story about some young black day campers getting kicked out of a private swim club pulled back the curtain on a dirty, but poorly-kept secret, and then went viral and made our town the shame of a wired nation. Though the incident happened just across the county line in Huntingdon Valley, Lower Montgomery County is culturally indistinguishable from many outskirt neighborhoods at the city’s edge. In fact, if you drive a mile south of the pool itself you’re back in Philly. It’s all a part of what we know as the Greater Northeast, which the whole world now thinks is a haven for cold-hearted, Jim Crow bigots. The truth is a little more complicated, though no less depressing.

BY JEFF DEENEY Philadelphians know all too well that thinly-veiled racial tensions have been festering in the Greater Northeast long before the story about some young black day campers getting kicked out of a private swim club pulled back the curtain on a dirty, but poorly-kept secret, and then went viral and made our town the shame of a wired nation. Though the incident happened just across the county line in Huntingdon Valley, Lower Montgomery County is culturally indistinguishable from many outskirt neighborhoods at the city’s edge. In fact, if you drive a mile south of the pool itself you’re back in Philly. It’s all a part of what we know as the Greater Northeast, which the whole world now thinks is a haven for cold-hearted, Jim Crow bigots. The truth is a little more complicated, though no less depressing.

As you’re probably aware, Greater Northeast Philadelphia, generally speaking, is Frank Rizzo’s Philly. It’s comprised of a lot of white flight families who once lived in the old working class stronghold neighborhoods of North Philadelphia that were eroded by drugs and crime after industry collapsed. Many Greater Northeasters have spent the past 20-plus years harboring racial resentments against “those people” who they feel ruined their old neighborhoods. The ugliest side of this resentment is seen every day in the online comment sections of local crime stories in the Inquirer and Daily News. The Greater Northeast is heavily Republican, an angry red spot on a city map that runs deep Democrat blue. It’s a refuge for law enforcement officers, many of whom wish they could move even further away from the inner city but are constrained by residency requirements.

The picture is more complex than this, though this broad generality has shaped news coverage of the event. The Greater Northeast is also home to the region’s biggest Russian community – many signs here are in Cyrillic script. There is also a substantial Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, and some streets feel more like Crown Heights than a bucolic suburb. While many trucks and SUVs are adorned with glaring bald eagles and NRA member stickers, you also see Muslim women in ornate silk head scarves driving luxury coupes. Groups of Latino kids on summer break duck in and out of strip mall convenience stores. For a region that’s been portrayed as practically a sundown town it’s surprisingly diverse.

Greater Northeast is also home to the region’s biggest Russian community – many signs here are in Cyrillic script. There is also a substantial Orthodox Jewish neighborhood, and some streets feel more like Crown Heights than a bucolic suburb. While many trucks and SUVs are adorned with glaring bald eagles and NRA member stickers, you also see Muslim women in ornate silk head scarves driving luxury coupes. Groups of Latino kids on summer break duck in and out of strip mall convenience stores. For a region that’s been portrayed as practically a sundown town it’s surprisingly diverse.

The Valley Swim Club itself is low rent, the block it sits on in disrepair. The fence surrounding the club is rusted and falling down; tall weeds grow through cracks in the parking lot asphalt. Directly across the street is a vacant, run down office space whose grass looks like it hasn’t been cut since last year. This dispels the notions that have popped up online based on housing data figures and the like that this is a group of rich white suburbanites walled off from the world. This is Lower Montgomery County, folks. What happened at the swim club is situated more in the long tradition of Greater Northeast Philadelphia’s working and middle class white struggle with their stubborn generations-old xenophobia.

Next to the swim club is a cul-de-sac of tiny two story brick row homes. The sidewalk traffic is comprised of thickly bearded Orthodox men wearing black suits and yarmulkes under the summer sun. One of them introduces himself as Yaakov Abraham, a 31 year old Rabbi. He waves his hand, indicating the general area surrounding the Valley Swim Club.

“This is all Russian and Ukrainian immigrants, all Jewish.”

Has he experienced prejudice from his neighbors? If so, how did he respond?

“Some of these white trash types have screamed ‘Jew!’ at me when I’m walking with my family. But it’s not a big deal, because we are proud of what we are. A kid once spray painted a Swastika on my Synagogue’s door; he got caught, and was made to do community service. We didn’t make a big deal about it, you didn’t see any of this,” he says with disdain, indicating the giant, space-age looking CNN news van parked on the corner.

“I don’t understand,” he says, referring to the day campers, “why they have to make a big deal about it. Why can’t you just be proud of what you are and move on?”

Does he think his family would be welcome at the Valley Swim Club?

“I wouldn’t swim there, anyway. I’m a rabbi, I can’t do mixed swimming. I have laws to abide by,” he chuckles, “I have to watch my eyes, you know?”

Despite the fact that the area is more diverse than it’s been portrayed, don’t think the archetype Archie Bunker-esque white working class Northeast Philly guy is a thing of fiction. If you throw a rock around here, you’ll find one. And if you’re in the parking lot of Benny the Bum’s Crabhouse Bar on Bustleton Avenue, only a mile down the road from the Valley Swim Club, you’ll find a couple.

Despite the fact that the area is more diverse than it’s been portrayed, don’t think the archetype Archie Bunker-esque white working class Northeast Philly guy is a thing of fiction. If you throw a rock around here, you’ll find one. And if you’re in the parking lot of Benny the Bum’s Crabhouse Bar on Bustleton Avenue, only a mile down the road from the Valley Swim Club, you’ll find a couple.

Jerry Connelly, a general contractor, and his laborer assistant Donald Sinclair sit in a beat up white work truck with ladders lashed to the roof. They’re rough guys who hold generic cigarettes in thick fingers grey-tipped from dry wall plaster dust. Jerry says he moved here a long time ago from Fishtown, one of those aforementioned Philly working class stronghold neighborhoods. They’re affable guys, but at the same time they exude the embattled victimhood common to AM radio conservative talk shows. Once you get them going about race relations, they can’t stop.

“I can’t compete with these Mexicans,” Connelly says of his contracting business. “They all pile in one truck, all live in one apartment. They work cheap and then go back to Mexico and live like kings for two months.”

Sinclair jumps in, croaking overtop his boss in a heavy smoker’s froggy rasp, “You go to these Section 8 projects and what do you see? Brand new Lincolns, brand new boats; they know how to work the system.”

Connelly agrees, sounding particularly aggrieved, “We’re the minority now. We don’t qualify for nothin’.”

They hate the Russian signs they can’t read, and they don’t like people talking in foreign languages around them because you never know what they’re saying about you. But for all of what one could consider to be their small mindedness, even rough Northeast Philly contractor Jerry Connelly knows when a line has been crossed.

“That thing with those kids at the swim club, though? That was bullshit. They paid to swim, let ‘em swim. Black, white, who cares? They shouldn’t have kicked those kids out like that.”