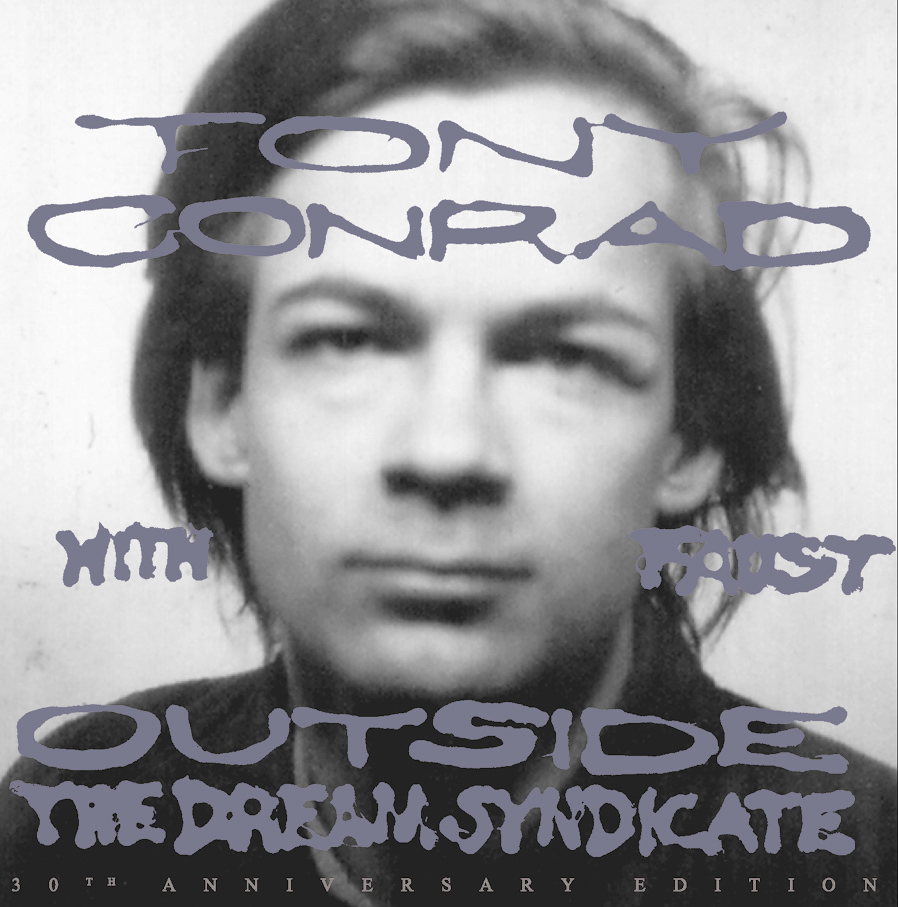

![]() BY JONATHAN VALANIA In 1965 Tony Conrad moved out of his New York City apartment, and like many people moving out he left behind a few items, one of which was a book. This is notable for three reasons: First, his roommate was John Cale, a classically-trained violist with a taste for the avant garde who, like Conrad, was a member of the Theater Of Eternal Music, a downtown collective of music-makers exploring infinite drone, endless improvisation and multi-media freakouts. Second, when Conrad moved out, Lou Reed moved in. Third, the book he left behind was a smutty S&M novel called…wait for it…The Velvet Underground. Conrad would go on to explore his dual interest in hypnotic experimental film-making and trance-inducing minimalist musical composition. His 1965 film The Flicker, consisting entirely of rapidly alternating black and white screens that create a stroboscopic effect and lures the viewer into a post-hypnotic state, remains a landmark of experimental cinema and has been screened at both the Museum of Modern Art and The Whitney. His early ’70s collaboration with legendary kraut-rockers Faust, Outside The Dream Syndicate, has become a touchstone of minimalist composition and, much like his association with the Velvets, a bridge between rock music and the avant garde. Conrad will perform Sunday night at Ars Nova/International House in tandem with Keiji Haino, Japan’s pre-eminent experimental music maker. This is not the first time the two have collaborated in a live setting, and sparks are expected to fly. Recently, Phawker got Conrad — who makes his living as a professor of media arts at the University of Buffalo — on the horn to talk about all the above.

BY JONATHAN VALANIA In 1965 Tony Conrad moved out of his New York City apartment, and like many people moving out he left behind a few items, one of which was a book. This is notable for three reasons: First, his roommate was John Cale, a classically-trained violist with a taste for the avant garde who, like Conrad, was a member of the Theater Of Eternal Music, a downtown collective of music-makers exploring infinite drone, endless improvisation and multi-media freakouts. Second, when Conrad moved out, Lou Reed moved in. Third, the book he left behind was a smutty S&M novel called…wait for it…The Velvet Underground. Conrad would go on to explore his dual interest in hypnotic experimental film-making and trance-inducing minimalist musical composition. His 1965 film The Flicker, consisting entirely of rapidly alternating black and white screens that create a stroboscopic effect and lures the viewer into a post-hypnotic state, remains a landmark of experimental cinema and has been screened at both the Museum of Modern Art and The Whitney. His early ’70s collaboration with legendary kraut-rockers Faust, Outside The Dream Syndicate, has become a touchstone of minimalist composition and, much like his association with the Velvets, a bridge between rock music and the avant garde. Conrad will perform Sunday night at Ars Nova/International House in tandem with Keiji Haino, Japan’s pre-eminent experimental music maker. This is not the first time the two have collaborated in a live setting, and sparks are expected to fly. Recently, Phawker got Conrad — who makes his living as a professor of media arts at the University of Buffalo — on the horn to talk about all the above.

*

PHAWKER: Starting back at the beginning, you studied mathematics at Harvard. I’m curious what attracted you to math in the first place, and what intellectual curiosities that satisfies.

TONY CONRAD: Well, nothing out of the ordinary. I had qualified in that area, and not knowing what else to do with my life, I started to study that because people said I was good at it.

PHAWKER: So you were a natural at math.

TONY CONRAD: It seemed that I was going to be natural at math, but in fact, It turns out there’s no such thing as natural. You need to work at these things, and I wasn’t interested in spending enough of my time at it. I learned that, effectively, through exposure to some pretty remarkable roommates who didn’t spend their time working to come up to speed in the field of math, most people around us in the world associate math with things like multiplying fractions or calculating the area of an irregular polygon, but actually, contemporary math has moved way beyond that sort of thing. I’m always accused of being involved with math, because of the fact that the music I do entails number ratios and calculations of frequency ratios, and other proportionality relationships that I get stuff in, but to be honest, this stuff has nothing to do with mathematics.

PHAWKER: The music has nothing to do with math?

TONY CONRAD: Not math like its evolved during the last two thousand years.

PHAWKER: One last question on the math subject. If math is able to explain our reality, does that contradict the notion that reality is in some way subjective? If there is a mathematical framework then there must be an objective truth to reality.

TONY CONRAD: I would say none of that makes sense at all. Good question though. It’s more interesting to  ask questions that don’t make any sense. I’ll have to resort to my plan B, which would be to use a pre-arranged answer, which would be that it’s going to be a really great summer.

ask questions that don’t make any sense. I’ll have to resort to my plan B, which would be to use a pre-arranged answer, which would be that it’s going to be a really great summer.

PHAWKER: In doing some reading on you, I came across this quote that A, I wanted to confirm you said, and B, ask you to elaborate on that. The quote is “history is like music, completely in the present”. Can you put that in layman’s terms, because it seems counter-intuitive.

TONY CONRAD: Well it is in layman’s terms, but I could say a little more about that, why I would want to say something obviously so silly. The reason that I’m interested in trying to talk about history in a different way is that it comes from my experience in working with long durations. I’m thinking now of the way that in my early work in New York, playing music that used extended durations stretched the limits of the critical discourse of the time, and made the works seem very progressive and involved a kind of shift of paradigm in music altogether. By using longer durations, it was possible for me and the group I was working with to change the traditional focus of music activity away from the function of the composer and to turn it in the direction of space and subjective impressions, in particular, related to trance and quasi-hypnotic states, and to take that kind of material and reposition it so that it achieves some kind of relevance in the western tradition of music. I think that, in a way this was important because of what John Cage had done earlier with a piece that everybody knows about called “4 Minutes And 33 Seconds,” which was pure duration. It would be seen as pure duration from one  point of view, just like “4 Minutes And 33 Seconds” with those found prescribed to what had occurred in that time span . In that respect, this was the opposite than what had been emerging as the dominant kind of music in Europe, which was very much a kind of constructivist music. It was music that had been pieced together out of broken down parts. Just fragments of organized structures of time or formal elements of music. Instead, this made music completely transparent, and turned it from poetry into a novel. The music of long duration followed in this direction, sort of “let’s stretch the novel out.” I felt the study of long durations is very productive. Of course, human beings only live to be so old so that they really never have experiences of truly, historically long durations. Nobody lives for a thousand years. But at the same time, the events of a thousand years ago are only out of reach in the same way that the events of yesterday are out of reach. We can lose sight of the fact that a thousand year duration is somehow important to us in the same way that an hour or a day is. I like to refocus that and sometimes to try to bring the richness of our historical tradition within reach of the work that I’m doing, to comment on it and to find the knots in the narratives that it conveys.

point of view, just like “4 Minutes And 33 Seconds” with those found prescribed to what had occurred in that time span . In that respect, this was the opposite than what had been emerging as the dominant kind of music in Europe, which was very much a kind of constructivist music. It was music that had been pieced together out of broken down parts. Just fragments of organized structures of time or formal elements of music. Instead, this made music completely transparent, and turned it from poetry into a novel. The music of long duration followed in this direction, sort of “let’s stretch the novel out.” I felt the study of long durations is very productive. Of course, human beings only live to be so old so that they really never have experiences of truly, historically long durations. Nobody lives for a thousand years. But at the same time, the events of a thousand years ago are only out of reach in the same way that the events of yesterday are out of reach. We can lose sight of the fact that a thousand year duration is somehow important to us in the same way that an hour or a day is. I like to refocus that and sometimes to try to bring the richness of our historical tradition within reach of the work that I’m doing, to comment on it and to find the knots in the narratives that it conveys.

PHAWKER: Can you explain the distinction between Theater of the Eternal Music and Dream Syndicate? Why are there two different names, and do they essentially describe the same thing?

TONY CONRAD: Well, there was a collaboration going on around 1962-1965, and this collaboration was a  little bit loose. It was largely a discipline by (inaudible), who had a loft where we gathered, and it was motivated by powerful beliefs among the group that the stuff we were doing was among the most interesting stuff of the time in music. Sometimes Jerry Riley would come or another musician that La Monte would happen to know. John Gale joined in with us, and stuck like velcro to this group. Angus McLise was there, but nothing like velcro. He was his own spirit, and took longer to get through and sometimes out of this orbit. La Monte Young and John Cale and I were generally there. We didn’t have a name for our ensemble, but after some length of time had passed, La Monte began to refer to it as the theater of eternal music, and that was OK with me at the time. Looking back on it, I realize that La Monte had a notion that these chords we were playing had gone on forever and we were just participating in them. Although this seemed fanciful and kind of attractive as a kind of narrative to me at the time, subsequent to that, I felt that this kind of goes over into a kind of idealism that’s really counter-productive, and it’s not as effective in terms of the kind of conceptual framework as it should be in order to represent the objectives and practices that the music was. I don’t really care for the term “Theater of Eternal Music” at all, personally. I wrote a piece about the music for an early issue of Film Culture magazine. When I did, I decided to call it Inside the Dream Syndicate, in part because I recognize the fact that this is a group effort, and in my writing about it, I was taking on the voice of the group, and in a way, I felt a little awkward about it, that is, I didn’t feel that any one of us could appropriately speak for the actions of the whole group. I decided that I would just refer to it and speak for myself rather than call it anything or name at anyone. I would just refer to this “Dream Syndicate” because we often called what we were doing as dream music, and dream music was a pretty good term for it.

little bit loose. It was largely a discipline by (inaudible), who had a loft where we gathered, and it was motivated by powerful beliefs among the group that the stuff we were doing was among the most interesting stuff of the time in music. Sometimes Jerry Riley would come or another musician that La Monte would happen to know. John Gale joined in with us, and stuck like velcro to this group. Angus McLise was there, but nothing like velcro. He was his own spirit, and took longer to get through and sometimes out of this orbit. La Monte Young and John Cale and I were generally there. We didn’t have a name for our ensemble, but after some length of time had passed, La Monte began to refer to it as the theater of eternal music, and that was OK with me at the time. Looking back on it, I realize that La Monte had a notion that these chords we were playing had gone on forever and we were just participating in them. Although this seemed fanciful and kind of attractive as a kind of narrative to me at the time, subsequent to that, I felt that this kind of goes over into a kind of idealism that’s really counter-productive, and it’s not as effective in terms of the kind of conceptual framework as it should be in order to represent the objectives and practices that the music was. I don’t really care for the term “Theater of Eternal Music” at all, personally. I wrote a piece about the music for an early issue of Film Culture magazine. When I did, I decided to call it Inside the Dream Syndicate, in part because I recognize the fact that this is a group effort, and in my writing about it, I was taking on the voice of the group, and in a way, I felt a little awkward about it, that is, I didn’t feel that any one of us could appropriately speak for the actions of the whole group. I decided that I would just refer to it and speak for myself rather than call it anything or name at anyone. I would just refer to this “Dream Syndicate” because we often called what we were doing as dream music, and dream music was a pretty good term for it.

PHAWKER: What year was this article written and term coined?

TONY CONRAD: I would say 1966. Then, in ’72, when I decided go out on my own, I still felt like, well, I was  working with La Monte and John, and so forth at that time, but here I am on my own, so I decided last time it was the Dream Syndicate, but now its outside the Dream Syndicate, so I called the record that I made “Outside the Dream Syndicate,” but the group never called themselves the Dream Syndicate. In some sense, it really was a name for it.

working with La Monte and John, and so forth at that time, but here I am on my own, so I decided last time it was the Dream Syndicate, but now its outside the Dream Syndicate, so I called the record that I made “Outside the Dream Syndicate,” but the group never called themselves the Dream Syndicate. In some sense, it really was a name for it.

PHAWKER: Getting back to these early gatherings, basically when you guys would get together, everyone would take up instruments, and would you roll tape all the time?

TONY CONRAD: Depended. We did a lot of recordings

PHAWKER: How long would these pieces go on for? Lengthy? Are we talking half hour presentations?

TONY CONRAD: It varied quite a bit. Early on, some of the pieces were shorter. In particular, when I started working with the group, La Monte was playing saxophone, and that’s a very demanding instrument. He didn’t really just keep blowing the sax at top speed, which is what he was up for. He couldn’t do that for an hour at a time. He could do it for a lengthy time, but then he would have to pause, and pausing was not generally our bag. There were some shorter takes, but occasionally we were playing for an hour or more, and it varied day to day. I don’t have an accounting, although I’ve asked La Monte in the past to sort of provide an inventory of the recordings that we’ve made, I still haven’t seen one.

PHAWKER: And there are, I’ve read by your estimation, hundreds of these recordings?

TONY CONRAD: I don’t have any idea, and I couldn’t say. Anything I said would be a guess, and I’ve never been allowed to have an inventory, although I’ve gathered that La Monte has been able to archive all this methodically.

PHAWKER: When did you start falling out with La Monte? Was it all about authorship?

TONY CONRAD: Well, I guess it didn’t help our personal relationship that I decided that the differences we had over authorship were amounted to a kind of art politics issue. I mean, it was about intellectual property in a way in collaboration, and how to deal with that, so I felt it would be appropriate to picket him when he came to Buffalo and just because that’s a political tool being applied to whatever situation, and I got the sense that, when I picketed him, he didn’t take this as an art gesture, which I felt it was. He took it more as a personal assault, and at that point, I had developed a feeling that the indifference that he showed towards my interest in hearing the music I had made with the group was so callous that I could hardly attribute that to any kind of friendship at all. I don’t know when the falling out began because I don’t know when his unfriendliness began. It certainly began to appear as early as the ’70s, and it began to appear that he was not going to honor the agreements we set up to share the recorded material. Maybe that’s when that started.

PHAWKER: This picketing, when exactly did that occur?

TONY CONRAD: I have some files I can search through to get an answer to that while we’re talking.

PHAWKER: OK. Where did this interest in trance music first form? Were you exposed to eastern music?

TONY CONRAD: I remember when the first Indian music record was released on an English label. I happened to hear it because my friend had acquired a copy somehow. I was very impressed by the fact that it was music that was based off particularly on one continuous note. That attracted me a lot.

PHAWKER: Was there any experimentation with psychedelic drugs at this point that informed this appreciation for this kind of music and interest in exploring it, or is that beside the point?

TONY CONRAD: It’s largely beside the point in some respects, but let’s put it this way. The fact that people at this time were learning about psychedelic drugs and various kinds of drugs including grass and hash. The fact that these were beginning to be explored actively among Anglos as opposed to persons of color who had this active element in their music culture earlier, it was the harbinger of the 60’s. It created a new experiential terrain in which people devoted attention in an unusually focused way to the kind of experience and pleasure that goes with exposure to a different kind of internal psychic environment. Getting high, so to speak, turns one’s attention in a direction of internal experience that would otherwise be difficult to explore. Drugs immediately brought it into focus, and maybe very insistently, for example with psychedelic drugs. This didn’t necessarily directly influence the idea that there’s psychedelic music and its behind this, its a bit of a stretch. On the other hand, the kind of experiential circumstances obtained when we were working with very long durations  was interesting to us in the way that was having kinship to having the experiences tied to drug experiences, so there’s a connection, but its more goofy than one might suggest.

was interesting to us in the way that was having kinship to having the experiences tied to drug experiences, so there’s a connection, but its more goofy than one might suggest.

PHAWKER: Were you investigating firsthand these similarities?

TONY CONRAD: Oh, with caution. Found the file, the picketing occurred April of 1990.

PHAWKER: On a related note, this is another quote about La Monte that I’ve read attributed to you, and I’d like to confirm that you’ve said this, and explain it to me. Quote “It’s conservative gutting of the theater of eternal music has paid off to him in multi-million petro dollar bonanza which he uses to perpetuate his exploitative and artistically mindless enterprise”. What is this petro dollar connection?

TONY CONRAD: Oh, well that’s an ancient quote, and I don’t think its any longer relevant. I can’t comment on anything having to do with La Monte’s finances right now, because I really have no idea at all. The petro dollar thing, you’d have to talk to La Monte about that. From what I understand, he charges a lot for interviews.

PHAWKER: Supposedly, you are attributed with introducing the name “Velvet Underground” to the band?

TONY CONRAD: I owned the book, but they chose the title.

PHAWKER: So you had a copy of the book called “Velvet Underground.” I’ve been curious over time, would this be characterized as a pornographic novel?

TONY CONRAD: It’s sort of a study of suburban soft core S&M. That’s what it’s about, yeah. It was racy at the time.

PHAWKER: John Cale was in the Theater of Eternal Music at the time too, and you just happened to have a  copy of this book on you and he just saw it?

copy of this book on you and he just saw it?

TONY CONRAD: Well, we lived in the same apartment. When I moved out, I left the book there. When Lou moved in, there it was. They read it I guess, I don’t know what they did with it really, but they made a band. I wasn’t interested in being in a rock and roll band at the time, I was more interested in making movies.

PHAWKER: Around this time is when you did Flicker. Is that correct, 1965?

TONY CONRAD: A little after that, yeah.

PHAWKER: Can you tell me a bit more about that, the intention with The Flicker?

TONY CONRAD: Well, I really wanted to make a movie. I had worked with Jack Smith earlier, and we had a falling out. I realized if I was going to make sound for a movie, I would have to make the movie too. So I did.

PHAWKER: Where did you encounter the science behind the concept of the movie?

TONY CONRAD: Well, there’s not much science in the mix, but to the degree that there was, I was aware of that because I had studied that at Harvard. I took a course in neurophysiology. It happened to be a course in which we learned a considerable amount about inter-cranial cell stimulation, flicker, and a couple other methodologies. Areas which had to do with then-current areas of inquiry in dealing with physiological psychology.

PHAWKER: This warning that came with the film, the producers, distributors waive all liability, blah blah  blah, is that for real, or was it showmanship? I do understand this sort of imagery disturbs an amount of the population.

blah, is that for real, or was it showmanship? I do understand this sort of imagery disturbs an amount of the population.

TONY CONRAD: Yeah, so it could be a little of both. The reason I decided in the end the reason it should be in rather than out is that there really are some people out there that are affected, so I felt they should know.

PHAWKER: Were there any of these incidents?

TONY CONRAD: Yeah, sure. There’s a condition known as photogenic migraine that I didn’t know about at the time, but its much more prevalent than photogenic epilepsy. There were a couple occasions where people did have really bad headaches after watching the film. I’ve only heard very isolated reports about seizures, and I’ve never been in the presence of any of them.

PHAWKER: I was reading, I believe on your Wikipedia page, that your son is making a digital version of this? When will this be released and in what format?

TONY CONRAD: Digital format. I don’t know how to describe the outcome until its ready to come out, but that’s something that’s definitely going to happen.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk a bit about your life these days. You’re teaching at…

TONY CONRAD: University of Buffalo, department of media studies.

PHAWKER: So what exactly are you teaching?

TONY CONRAD: Video. Video both from a critical and historical perspective, and also production.

PHAWKER: And how long has that been the case?

TONY CONRAD: A long time. Since the ’70s.

PHAWKER: So when you come to Philadelphia, can you tell us a bit about what to expect with the performance you’re planning?

TONY CONRAD: Well this is going to be a collaboration with Keiji Haino, and we first crossed paths when I started working with Table of the Elements. It’s a small label that’s basically run by one guy, Jeff Hunts. Jeff was remarkable for singling out some of the most adventurous non-academic musician he could find and putting them out on discs in really nice editions. The editions were small and it was really tough to find enough copies to satisfy his audience, but nevertheless, it was good stuff. He focused on the rock side of things, to a great extent. Keiji Haino is one of the most adventurous and durable experimental rock performers in Japan. He’s a person who’s music is of extraordinary power and directness. He’s the guitar virtuoso, but also has a wide scope of accomplishments that covers a diverse and very sensitive musicianship. His stage style is extreme vigor, and i was going to say energetic, but that really doesn’t even touch it. I was impressed by his work, how extreme it is and how direct he was in the way he connected with people. When the opportunity rose at one point, as much as 10 years ago to play a short set with him in Tokyo, I was happy to do it, and it seemed to work. Then we decided to play together at a festival in Glasgow, sometime early this decade. The set we did, which was heavy improvisational was really excellent. Somebody put chunks of it online. It got widely viewed, and it was almost as successful online as I wished it to be. Last year, when I was at Yokahama for the Yokahama triennial, which is a big art fair I was invited to participate in, I was happy to find the opportunity to go up to Tokyo and do a couple sets with Keiji at a place called Super Deluxe. It’s like an adventurous club theme. The fact that Keiji lives near Tokyo, he was able to bring a truckload of different instruments. We launched into a couple sets that were really extraordinary. It was an improvisational theme that ranged from playful to extremely intense, and  sometimes had a kind of spiritual overtone, but became completely complex, tangled in masses of sound. It was extreme and very unusual, and I’ve mentioned this set to people I’ve worked with and everybody, I think, is excited to see him come to the United States, and I think people are eager for a chance to experience this collaboration between us, because so far, it’s just been extraordinary. I think that this event in Philadelphia will be the peak of our mini-tour because we’re going to have a concert in New York which will be a warm-up, then we go to Philadelphia to really do the big thing, and it’s just going to be too much. We have a final concert in Chicago that will kind of wrap things up, but I am really looking forward to the show in Philadelphia because I think it’s going to be a once in a lifetime moment. Time has shown that the two of us somehow have a way of being very different from one another, but cross spaces very effectively. Each of us in our old years is a peak experimentalist and improviser with an enormous background of experience. Keiji’s background is law, he’s made more albums than anyone else I know. He’s made scads of albums every year, and I’ve been doing what I do since ’63. We’re bringing a lot to play in top form. I remember seeing Bo Diddley when he was 72, and he was onstage, and I remember thinking well, he’s not quite working at top form, but on the other hand he’s really cooking and in a way, I think we have a different approach to music, almost like classical musicians. In the sense that most classical musicians seem to get better, I think this is tip top stuff. Like I said, we’ve got some great stuff and I think it’s gonna be really fun.

sometimes had a kind of spiritual overtone, but became completely complex, tangled in masses of sound. It was extreme and very unusual, and I’ve mentioned this set to people I’ve worked with and everybody, I think, is excited to see him come to the United States, and I think people are eager for a chance to experience this collaboration between us, because so far, it’s just been extraordinary. I think that this event in Philadelphia will be the peak of our mini-tour because we’re going to have a concert in New York which will be a warm-up, then we go to Philadelphia to really do the big thing, and it’s just going to be too much. We have a final concert in Chicago that will kind of wrap things up, but I am really looking forward to the show in Philadelphia because I think it’s going to be a once in a lifetime moment. Time has shown that the two of us somehow have a way of being very different from one another, but cross spaces very effectively. Each of us in our old years is a peak experimentalist and improviser with an enormous background of experience. Keiji’s background is law, he’s made more albums than anyone else I know. He’s made scads of albums every year, and I’ve been doing what I do since ’63. We’re bringing a lot to play in top form. I remember seeing Bo Diddley when he was 72, and he was onstage, and I remember thinking well, he’s not quite working at top form, but on the other hand he’s really cooking and in a way, I think we have a different approach to music, almost like classical musicians. In the sense that most classical musicians seem to get better, I think this is tip top stuff. Like I said, we’ve got some great stuff and I think it’s gonna be really fun.

PHAWKER: Well, I look forward to seeing you Sunday.

TONY CONRAD: Alright, nice talking to you.

***

Tony Conrad will perform with legendary Japanese avant gardist Keiji Haino Sunday at Ars Nova/International House.