STATE OF PLAY (2009, directed by Kevin McDonald, 127 minutes, U.S.)

STATE OF PLAY (2009, directed by Kevin McDonald, 127 minutes, U.S.)

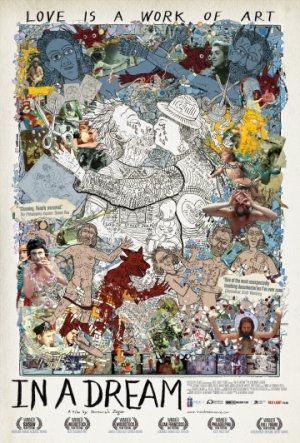

IN A DREAM (2008, directed by Jeremiah Zagar, 80 minutes, U.S.)

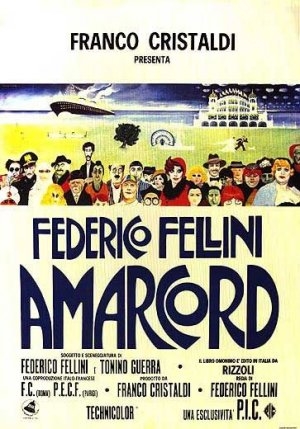

AMARCORD (1973, directed by Federico Fellini, 127 minutes, Italy)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

Russell Crowe is the gladiator of the fictional Washington Globe in State of Play, a new thriller based on the BBC miniseries of the same name. From the bustling newsroom we glide through in the film’s opening to the montage of headlines going to press at the close, this unimaginative yet sturdy whodunit seems almost quaint in the face of the collapse of print journalism. If the script was put into production today it might need to be reconfigured as a period piece.

Russell Crowe plays star investigative reporter Cal McCaffrey, an irascible hard-drinking newsman who may frustrate his editor (Helen Mirren) but who is given a wide-berth because he has newsprint in his blood. His latest story presents itself when his old college roommate, Congressman Stephen Collins (Ben Affleck, taking advantage of his superficiality) shows up on his doorstep when the aide Collins has been sleeping with falls in front of a D.C. commuter train. In untangling the story McCaffrey must face off against a renegade employee of a Blackwater-type defence contractor, the Congressman’s amorous wife (Robin Wright Penn), an inexperienced blogger from the paper’s online site and assorted morgue attendants, cops and whistle blowers.

Its busy plot was presumably fleshed out in its original six-hour BBC form; here the script co-authored by Michael Clayton screenwriter Tony Gilroy is so overstuffed with incident and character that it is easy to overlook its pedestrian story in the face of such restless momentum. Russell Crowe gets by on whatever movie star magnetism shines through his lazy performance; like Richard Burton is the 1970s, you almost think Crowe took the job because he would not have to shave or get into shape.

Another anachronism that pops up is the fact that the Washington Globe is ready to be swallowed by a consolidating newspaper chain (remember when newspapers were hot commodities?) and the new owners will not appreciate their star reporter’s muckraking investigations. State of Play suffers from a similar timidity when it floats a plot turn that the Blackwater stand-in has plans to stage a domestic coup. Somehow this juicy and topical idea of unregulated power gets tossed aside in the wake of new revelations about BenAffeck’s scheming Congressman. If Crowe’s crusading reporter ends up triumphant it is sad that the script lets its most promising suspect get off scot-free.

– – – – – – – – –

The short list of great Philadelphia movies just grew one film longer with the arrival of Jeremiah Zagar’s  documentary In A Dream. The film is Zagar’s debut and the subject fell right into his lap; In A Dream tells the story of Jeremiah’s father, Philly mosaic artist Isaiah Zagar. His large mosaic murals will be familiar anyone who has attended the Painted Bride or strolled along South Street and this rich and emotional documentary will give you further insight into the ideas that are explored inZagar’s work.

documentary In A Dream. The film is Zagar’s debut and the subject fell right into his lap; In A Dream tells the story of Jeremiah’s father, Philly mosaic artist Isaiah Zagar. His large mosaic murals will be familiar anyone who has attended the Painted Bride or strolled along South Street and this rich and emotional documentary will give you further insight into the ideas that are explored inZagar’s work.

Beyond that, In A Dream is a fascinating domestic drama, as Jeremiah started filming right around the time that Isiah has decided to leave his long-time wife, Julia Zagar of South Street’s Eyes Gallery. Actually, the separation could be a plot line in any run-of-the-mill reality TV show, it’s through the filter of Isaiah’s restless creativity that this story takes on its depth. Using notebooks and artwork that Isaiah has spent a lifetime creating, we see his biography (which includes sexual abuse and mental illness) intimately illustrated and brought to life through digital animation. Julia and Isaiah’s separation goes none too well; as soon as he moves his mattress from the house Isaiah appears to disintegrate, figuratively, before our eyes. Just like the art he makes, Isaiah needs to break his life into pieces to understand what it really means. Going beyond his murals decorative exteriors, In A Dream brings a depth and understanding to Isaiah’s work that is made all the more moving when explained and examined by his own son. With Zagar’s work so ubiquitous locally, the film will make you appreciate Philadelphia more, however you don’t have to be from Philly to be moved by this perceptive artistic biography.

– – – – – – – – – – – – –

Also opening for a revival this week is what is popularly acknowledged as Italian master Federico Fellini’s last masterpiece, 1975’s Oscar winner for Best Foreign film, Amarcord. I have an affection for many of the stylistic quirks of ’70s film but Amarcord 1930’s setting and Fellini’s invisible craft is free of such tell-tale marks; the casually used adjective “timeless” really does apply here. In a visual symphony of rich earth tones (impeccably shot by Giuseppe Rotunno), Fellini resurrects the Italian village life of his youth. Along the way we follow the autobiographical coming-of-age of Fellini’s stand-in Titta, though Amarcord is constantly distracted from his story to show the lives of everyone in the village, from the town whore to the parish priest. As the seasons change, anecdote builds on anecdote and by the end of the journey you understand more than a character, more than a town: you understand something about the childlike soul of Italy itself.

Also opening for a revival this week is what is popularly acknowledged as Italian master Federico Fellini’s last masterpiece, 1975’s Oscar winner for Best Foreign film, Amarcord. I have an affection for many of the stylistic quirks of ’70s film but Amarcord 1930’s setting and Fellini’s invisible craft is free of such tell-tale marks; the casually used adjective “timeless” really does apply here. In a visual symphony of rich earth tones (impeccably shot by Giuseppe Rotunno), Fellini resurrects the Italian village life of his youth. Along the way we follow the autobiographical coming-of-age of Fellini’s stand-in Titta, though Amarcord is constantly distracted from his story to show the lives of everyone in the village, from the town whore to the parish priest. As the seasons change, anecdote builds on anecdote and by the end of the journey you understand more than a character, more than a town: you understand something about the childlike soul of Italy itself.

Left a mystery is the source of Fellini’s genius itself. In movie making the camera is turned on and sometimes a director gets more than they imagine, occasionally they are lucky enough to capture a magical moment, when a small detail or gesture tells you something undefinable about a place, person or time. Like so many of Fellini’s films, Amarcord makes the magic seems like it can be summoned on demand, as if the snow and the sun and a peacock’s plumage could be conducted to rise and dance at will. With Fellini making a rare appearance back on the big screen where he belongs, we are blessed that this most entrancing of films will be conjured for four shows a day, for the next week at least.