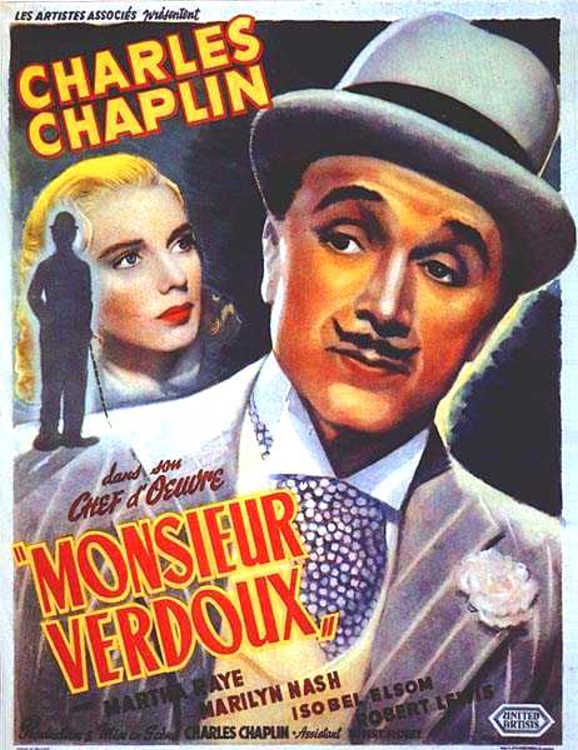

MONSIEUR VERDOUX (1947, directed by Charles Chaplin, 124 minutes, U.S.)

MONSIEUR VERDOUX (1947, directed by Charles Chaplin, 124 minutes, U.S.)

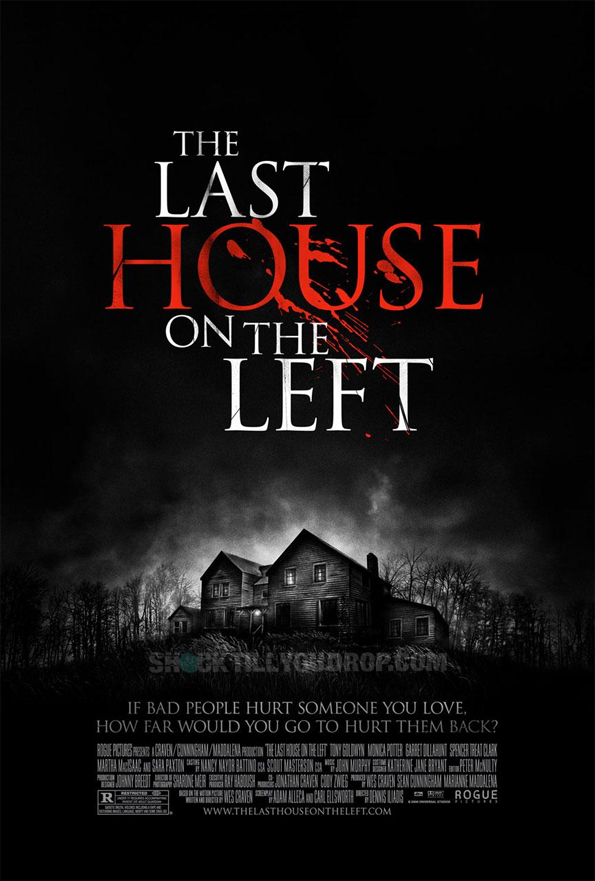

THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT (2009, directed by Dennis Iliadis, 100 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

This is what happens when a director takes career advice from Orson Welles. Released in 1947 and based on an idea that Orson Welles offered Chaplin (Welles was hoping to direct), Monsieur Verdoux found the fifty-eight year old comedian leaving behind the beloved “Little Tramp” character for the first time. In Monsieur Verdoux the star’s bird-like grace would be put to use to lend charm to a serial killer, a Bluebeard who woos and murders women for their money. It was “A Comedy of Murders” as the subtitle read, and the audience at the premiere hissed so much Chaplin reportedly fled the theater. The film’s glancing political commentary made Chaplin a target of the growing anti-communist sentiment in the U.S. and ultimately led to the film icon’s leaving the States to live in Europe.

Now back in theaters in an unexpected revival, Monsieur Verdoux remains disconcerting, as we laugh along at the absurdly nimble silver-haired gentleman who mixes poisons and burns the remains of a string of French widows after WWI. M. Verdoux didn’t start out this way, he was a nondescript banker until the 1929 crash of Wall Street left him unemployed and broke. A comment on the inhumane nature of the banking industry, M. Verdoux comes to the conclusion that “business equals murder” and goes about his new business free of conscious. It’s the blackness of Chaplin’s vision, perhaps more than the murders, that must have unsettled audiences. From the suspicious in-laws at the opening through a range of annoying battle-axes, Chaplin makes sure to only murder characters the audience would be glad to be rid of. The murders happen tastefully off-screen, it is the fact that the population is so murder-able that led audiences to be suspicious of the blackness in Chaplin’s heart.

Today, with shows like the serial killer dramedy Dexter, the black comedy of murder is comfortably “cutting-edge” enough edge for TV, giving the story an unusually modern sensibility while Chaplin’s performance, filled with fussy and concise details of pantomime, at times make the film feel oddly anachronistic for 1947. As a director Chaplin’s timing is as dead-on as ever; scenes like the one where Verdoux tries to decide how to kill the vulgar Martha Raye in a tiny rowboat still find ways to surprise us and make us laugh. It’s those quick cuts to Verdoux counting the money afterward, the coldness of the transaction, that still have the ability to unnerve. Finally confronted with his deeds Verdoux states, “As for being a mass killer, does not the world encourage it? Is it not building weapons of destruction for the sole purpose of mass killing? Has it not blown unsuspecting women and little children to pieces? And done it very scientifically? As a mass killer, I am an amateur by comparison.” From the poverty of the Little Tramp, to the Hitler parody of The Great Dictator to the post-war societal criticism of Verdoux, Chaplin specializes in comedy you can’t dismiss, even six decades later.

– – – – – – – – – – – –

Also disturbing, but none-too-surprising, is the latest horror remake; this week they’re foisting something called The Last House On Left. The 1972 original was a sadistic and crude little quickie, famous for its grueling rape and murder of two hippie girls who catch the wrong ride to a rock concert. The film launched the career of Wes Craven, who between the Scream and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises is officially the Popentate in American Horror. Last House was loosely based on Ingmar Bergman’s Virgin Spring and the opening of this remake is so lush and bucolic (with Cape Town, South Africa standing in for upstate New York) and its domestic dramatics so underplayed it hems closer to Bergman than its grindhouse namesake. At times, the film is downright elegant, the last word that would ever be ascribed to the ’72 version.

Also disturbing, but none-too-surprising, is the latest horror remake; this week they’re foisting something called The Last House On Left. The 1972 original was a sadistic and crude little quickie, famous for its grueling rape and murder of two hippie girls who catch the wrong ride to a rock concert. The film launched the career of Wes Craven, who between the Scream and Nightmare on Elm Street franchises is officially the Popentate in American Horror. Last House was loosely based on Ingmar Bergman’s Virgin Spring and the opening of this remake is so lush and bucolic (with Cape Town, South Africa standing in for upstate New York) and its domestic dramatics so underplayed it hems closer to Bergman than its grindhouse namesake. At times, the film is downright elegant, the last word that would ever be ascribed to the ’72 version.

The film moves along like a dreamy coming-of-age story until an attempt to score some pot brings the bad guys around; not the drugged-out pseudo Mansons of the original but your garden variety scruffy-faced white trash movie thugs. The rape scene remains and is rough stuff but the very premise of the original, where the girl’s mother and father turn into blood-thirsty revenge-mongers, is turned into a much more conventional armed battle between a good Daddy and a bad one. The film is undeniably effective on a thriller level but in the end Last House serves as another example of how Hollywood knows exactly how to tear the heart out of any subversive property to leave the audience with a tidy little moral homily.