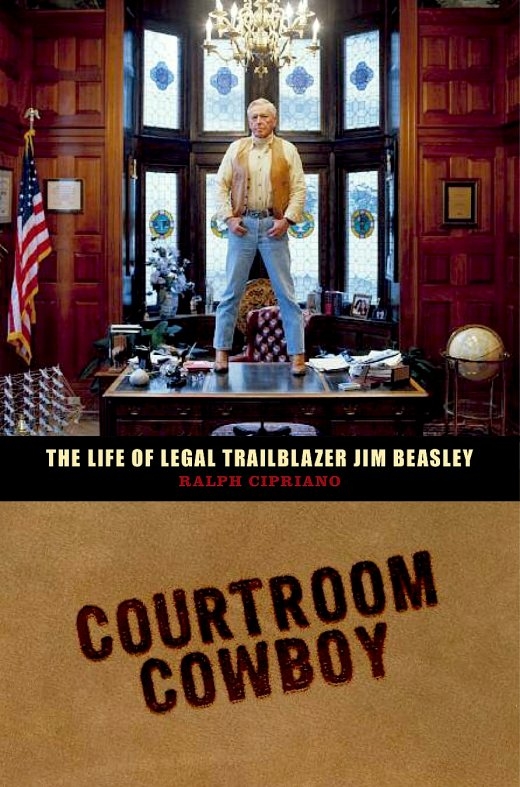

BY ADAM BONANNI Jim Beasley looks damn proud on the cover of his book, standing with John Wayne-like swagger atop his desk in his richly-appointed, oak-lined office suite. He has reason to be. Beasley and former Inquirer reporter Ralph Cipriano [pictured, below left] have gathered their favorite cases of Beasley’s long, impressive career as a crusading plaintiff’s attorney between the covers of Courtroom Cowboy. Beasley comes across as a hard-nosed, steadfast litigator who exudes charisma and never did believe in the phrase “backing down.” If you don’t back down in court from Don King, Ira Einhorn, Osama Bin Laden, or your wife, you just don’t back down ever.

BY ADAM BONANNI Jim Beasley looks damn proud on the cover of his book, standing with John Wayne-like swagger atop his desk in his richly-appointed, oak-lined office suite. He has reason to be. Beasley and former Inquirer reporter Ralph Cipriano [pictured, below left] have gathered their favorite cases of Beasley’s long, impressive career as a crusading plaintiff’s attorney between the covers of Courtroom Cowboy. Beasley comes across as a hard-nosed, steadfast litigator who exudes charisma and never did believe in the phrase “backing down.” If you don’t back down in court from Don King, Ira Einhorn, Osama Bin Laden, or your wife, you just don’t back down ever.

Beasley and Cipriano met in 1998 when Cipriano, then a reporter for the Inquirer, was publicly defamed by his boss Robert Rosenthal in the pages of the Washington Post. Cipriano worked the religion beat for the Inquirer and in the course of his reporting uncovered the Philadelphia Archdiocese’s lavish spending at the same time it was closing schools and parishes in the poorest sections of the city. Brian Tierney, currently the owner of the Inquirer but back then a PR flack representing the archdiocese, led the fight to get the stories shut down. Tierney played hardball and took the fight to the executive suites of 400 North Broad which, presumably, caved into pressure and sent an edict from on high that Cipriano was to be muzzled.

Told that his stories about the archdiocese would no longer be welcome in the pages of the Inquirer, Cipriano published them in The National Catholic Reporter, a national independent paper with a hard-won rep for aggressively watchdogging the Catholic church. This resulted in Washington Post media affairs columnist Howard Kurtz calling up Rosenthal and asking him why the story ran in the NCR instead of the Inquirer, to which Rosenthal carelessly responded that Cipriano’s reporting on the story was unsound. It was a comment Rosenthal would live to regret, resulting in a costly libel suit that would reward Cipriano with both an apology and a large financial settlement from the newspaper.

Told that his stories about the archdiocese would no longer be welcome in the pages of the Inquirer, Cipriano published them in The National Catholic Reporter, a national independent paper with a hard-won rep for aggressively watchdogging the Catholic church. This resulted in Washington Post media affairs columnist Howard Kurtz calling up Rosenthal and asking him why the story ran in the NCR instead of the Inquirer, to which Rosenthal carelessly responded that Cipriano’s reporting on the story was unsound. It was a comment Rosenthal would live to regret, resulting in a costly libel suit that would reward Cipriano with both an apology and a large financial settlement from the newspaper.

But Cipriano’s case is just the tip of the iceberg. In the course of his storied legal career, Beasley went toe to toe with the likes of Don King (who called Beasley “one fightin’ motherfucker”), Ira Einhorn, Osama Bin Laden, and his own wife. Cipriano’s vivid writing and attention to detail makes for a damn fascinating read. Unfortunately, Beasley didn’t live to see his story in hardback form, but he left behind dozens of fascinating cases, as well as a noble rep for always fighting the good fight for the little guy. Recently, Phawker sat down with Cipriano to discuss his book, his case and the state of newspapering.

PHAWKER: So what was the main reason for sitting down and writing this book?

CIPRIANO: Well, it was a job. Let’s just say, at the time, my career path opened up. I was unemployed, and Beasley said to me “you’ve got nothing to do and I want to write a book, so why don’t you come work for me”

PHAWKER: As take-no-prisoners plaintiff’s lawyer, Beasley made a lot of enemies out of doctors, other lawyers, and the press. How did that come back to bite him in the ass?

CIPRIANO: Well in the book, in the chapter about flying, it’s revealed his lifelong fear would be that he would end up in some hospital, in some emergency situation, and look up and see some doctor that he screwed in a malpractice case and the doctor would get even with him. (laughs) The way he went out, it makes you wonder.

PHAWKER: You mentioned he was very intimidating when you first met him. Did that impression change over time?

CIPRIANO: He just had this no nonsense air, like you don’t waste his time. He had this stare that kind of scared the shit out of a lot of people. One of the Inquirer’s lawyers wouldn’t even get on the phone with him, wouldn’t take his calls. However, because I became his client, and we were on the same team, although clearly he was the captain, there was definitely a camaraderie. Definitely a fun guy.

PHAWKER: Let’s talk about your libel case against the Inquirer. Can you give a brief summary of what happened?

CIPRIANO: Well, in a nutshell, I wrote a story that my newspaper didn’t want to print. We had an archbishop who was, at the same time closing poor churches and schools in the inner city, black and Hispanic, he was secretly spending $5 million for himself. He had a shore house, a 30 room mansion that he lived in, he was redecorating his offices; just having a grand time and keeping it secret. I had the documents, my newspaper wouldn’t print it and I was told I was anti-Catholic. So I shopped my story to a Catholic newspaper, and they printed the whole story, the National Catholic Reporter. It goes out, and Howie Kurtz of The Washington Post picks up the phone and calls my editor Bob Rosenthal and says “Why didn’t you run the story?” Rosenthal, at that point, could either admit the truth, that the paper didn’t have the balls to do it, or he could blame me, and he blamed me. He said I wrote stuff that wasn’t true, that I had an agenda, and a few other things that weren’t true that I’d like to forget at this point. He wouldn’t apologize, and about 45 of my colleagues, people who didn’t like me, went to him and said “this looks bad for all of us, you have a dishonest reporter here, people are going to wonder how many others you have. You really need to apologize,” but he refused to do it. So I went to see Jim Beasley, and we ended up suing Rosenthal for libel. A few years later, it all came to a happy conclusion when they printed a public apology and paid an undisclosed financial sum. It turned out well.

PHAWKER: What was the effect on your career after being defamed by your own paper?

CIPRIANO: Well, hah, my career was over in newspapers. You know, whose going to hire me? You can’t win. After a case like that, you’re either the guy who writes things that aren’t true, or the guy who goes crazy and sues his own newspaper for libel. [chuckling] Who wants that guy?

PHAWKER: So you’re working for the Beasley firm now. What is your position?

CIPRIANO: My position is kind of a fraud actually (laughing). I wrote the book, and then I started helping Jim Beasley Jr. with the website beasleyfirm.com. If you look at it, I’ve been covering the Vince Fumo trial. We decided that, instead of putting the usual PR information about the firm, we could actually make it an interesting site and cover stories people might want to read. I’ve been covering the Fumo trial since October, and we’ve been having a lot of fun working on the site. I’m also promoting this book, and trying to move copies.

PHAWKER: So you were raised Catholic, is that right?

CIPRIANO: I was. It didn’t take.

PHAWKER: Was there any kind of internal conflict about going after the archdiocese in your story?

CIPRIANO: Oh, it was a no brainer for me. I figured my grandmother, my mother, all Catholics would want to know this kind of stuff. At the time, this is one layer under, the archdiocese was running this $100 million fundraising campaign where they were trying to convince everyone they had this horrible financial crisis. Couldn’t have been that bad if they had the leftover to redecorate a shore house. I thought all Catholics would want to know this, and I had a duty to tell them.

PHAWKER: According to your book, the archdiocese has a long history of tangling with the Inquirer. Can you give some background on that? What kind of pressure were they putting on the Inquirer for your case?

CIPRIANO: Bad. A bad history. You have both sides just legally distressed at each other. I was a religion reporter for a couple years, and the vast majority of journalists I found, myself included, were full-on skeptics. Anybody “religious” was some kind of whack job, so both sides viewed each other with suspicion. The Catholic Archdiocese felt that the Inquirer was out to get them, so that’s the historical relationship. As for the pressure on the paper, it was simple really. There were three different meetings that the diocese demanded with my editors. There were PR people on one side, led by Tierney, and a bunch of editors who were afraid of them on the other side, and me, and I was ordered that I could never speak at any of the meetings since my editors feared that I would further antagonize the archdiocese. These meetings were just very one-sided; Tierney and his cohorts would just browbeat the editors for being anti-Catholic, and me for being out to get them.

PHAWKER: I thought that was a bit hypocritical of Rosenthal to slam you for being suspicious when he stated that the ideal person for the religion beat should be a skeptic.

CIPRIANO: Well at one time we were actually friends. Well, I wouldn’t say friends, but I always admired him. During the Cuban missile crisis, they sent the rebels in there without any cover. Well, that’s kind of what happened to me. This guy sent me out on a mission and said “I want a guy who doesn’t buy into any of this stuff. I want you to go out there and stir things up.” Well, that’s exactly what I did, and he forgot to tell me kid, this isn’t your night.

PHAWKER: What effect did your case have on the Inquirer? Did they report on themselves getting sued?

CIPRIANO: They did. They sort of had no choice since it was on the AP wire, so they printed a couple stories about it. They always considered me a problem. I listed the review they wrote on courtroomcowboy.com, and Angelo Cataldi, the WIP guy wrote a nasty letter to the Inquirer in my defense. They basically trashed me in the review. I don’t think they’re fond of me, but I can understand.

PHAWKER: According to your book, Brian Tierney was constantly antagonizing the Inquirer. How has he changed the paper?

CIPRIANO: I haven’t been there in 10 years, so I only know as a casual reader online. I would just say I haven’t seen any major changes, it just seems like its continuing its slide downward. I don’t see anything daring. The only thing I’ve seen is he’s brought in a bunch of columnists that couldn’t have bought their way in when I was there. Michael Smerconish would never have gotten a column when I was there since he was considered a right-winger. Rick Santorum, I don’t think would’ve gotten a letter to the editor printed.

PHAWKER: So how do you feel about the Inquirer now?

CIPRIANO: Well they still do some things very well. They have a lot of excellent journalists out there. Bill Marimow who runs the place, I have the highest respect for. I worked for him when he was the city editor, and he was just absolutely grade A. So, they’re trying to do more with less. It’s a tired cliche, but sometimes it shows. My general take on the Inquirer, if I had to get on my soapbox, is that since they’re going down, they might as well take some chances. If I was at the paper, I would be trying to talk people into doing riskier stories and trying to tackle more aggressive things rather than investigating the usual suspects. Vince Fumo, the Philadelphia Police, DHS, that’s all they’re interested in.

PHAWKER: Have you seen any evidence of harder hitting stuff lately?

CIPRIANO: Well, they’ve been really hard on Vince Fumo, who is apparently the only corrupt politician in Philadelphia.

PHAWKER: You would think. So what’s your take on journalism as an industry now?

CIPRIANO: Well, I think it’s a wonderfully exciting time to be a journalist. Turn the clock back to the Paleozoic era when I was coming up, the Watergate era, it was ossified. There were the top papers, and you could never break into the big time. Now, a citizen blogger goes into a caucus with Bill Clinton or Obama, they have their tape recorder on and get a great quote, 10 seconds later it’s around the world. It’s just become such a wide open field, and it’s such an incredibly exciting time to be a journalist, especially if you’re young.

[Cipriano photo by TIFFANY YOON]