REUTERS: Abraham Lincoln ranks first in leadership skills among the 42 former White House occupants, according a C-SPAN survey of 65 presidential historians released on the eve of the Presidents Day holiday. It’s a repeat performance for the 16th U.S. president, who also took the top spot in the first ”Historians Presidential Survey” by the cable television network in 2000. At No. 36, George W. Bush ranks near the bottom of the 2009 survey. MORE

THE NATION: Abraham Lincoln has always provided a lens through which Americans examine themselves. He has been described as a consummate moralist and a shrewd political operator, a lifelong foe of slavery and an inveterate racist. Politicians from conservatives to communists, civil rights activists to segregationists, have claimed him as their own. With the approach of the bicentennial of his birth, the past few years have seen an outpouring of books on Lincoln of every size, shape and description. His psychology, marriage, law career, political practices, racial attitudes and every one of his major speeches have been subjected to minute examination.

Lincoln is important to us not because of his melancholia or how he chose his cabinet but because of his role in the vast human drama of emancipation and what his life tells us about slavery’s enduring legacy. In the wake of the 2008 election and an inaugural address with “a new birth of freedom,” a phrase borrowed from the Gettysburg Address, as its theme, the Lincoln we should remember is the politician whose greatness lay in his capacity for growth. Much of that growth stemmed from his complex relationship with the radicals of his day, black and white abolitionists who fought against overwhelming odds to bring the moral issue of slavery to the forefront of national life.

Lincoln is important to us not because of his melancholia or how he chose his cabinet but because of his role in the vast human drama of emancipation and what his life tells us about slavery’s enduring legacy. In the wake of the 2008 election and an inaugural address with “a new birth of freedom,” a phrase borrowed from the Gettysburg Address, as its theme, the Lincoln we should remember is the politician whose greatness lay in his capacity for growth. Much of that growth stemmed from his complex relationship with the radicals of his day, black and white abolitionists who fought against overwhelming odds to bring the moral issue of slavery to the forefront of national life.

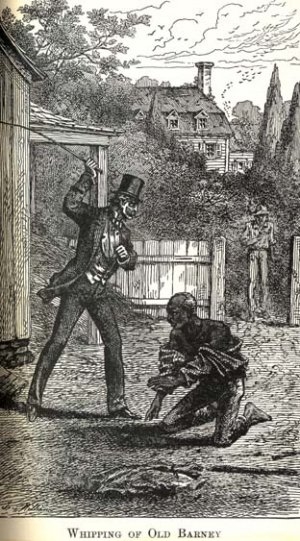

Until well into the Civil War, Lincoln was not an advocate of immediate abolition. But he was well aware of the abolitionists’ significance in creating public sentiment hostile to slavery. Every schoolboy, Lincoln noted in 1858, recognized the names of William Wilberforce and Granville Sharpe, leaders of the earlier struggle to outlaw the Atlantic slave trade, “but who can now name a single man who labored to retard it?” On issue after issue–abolition in the nation’s capital, wartime emancipation, enlisting black soldiers, amending the Constitution to abolish slavery, allowing some blacks to vote–Lincoln came to occupy positions the abolitionists had first staked out. The destruction of slavery during the war offers an example, as relevant today as in Lincoln’s time, of how the combination of an engaged social movement and an enlightened leader can produce progressive social change. MORE

WIKIPEDIA: The Emancipation took place without violence by masters or ex-slaves. The proclamation represented  a shift in the war objectives of the North—reuniting the nation was no longer the only goal. It represented a major step toward the ultimate abolition of Slavery in the United States and a “new birth of freedom”. Estimates of the number of slaves freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation are uncertain. But “a contemporary estimate put the ‘contraband’ population of Union-occupied North Carolina at 10,000, and the Sea Islands of South Carolina also had a substantial population. It seems likely therefore that at least 20,000 slaves were freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation.”[17]

a shift in the war objectives of the North—reuniting the nation was no longer the only goal. It represented a major step toward the ultimate abolition of Slavery in the United States and a “new birth of freedom”. Estimates of the number of slaves freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation are uncertain. But “a contemporary estimate put the ‘contraband’ population of Union-occupied North Carolina at 10,000, and the Sea Islands of South Carolina also had a substantial population. It seems likely therefore that at least 20,000 slaves were freed immediately by the Emancipation Proclamation.”[17]

Runaway slaves who had escaped to Union lines had previously been held by the Union Army as “contraband of war” under the Confiscation Acts; when the proclamation took effect, they were told at midnight that they were free to leave. The Sea Islands off the coast of Georgia were occupied by the Union Navy earlier in the war. The whites had fled to the mainland while the blacks stayed. An early program of Reconstruction was set up for the former slaves, including schools and training. Naval officers read the proclamation and told them they were free.

In the military, reaction to the proclamation varied widely, with some units nearly ready to mutiny in protest. Some desertions were attributed to it. Other units were inspired by the adoption of a cause that ennobled their efforts, such that at least one unit took up the motto “For Union and Liberty.” Slaves had been part of the “engine of war” for the Confederacy. They produced and prepared food; sewed uniforms; repaired railways; worked on farms and in factories, shipping yards, and mines; built fortifications; and served as hospital workers and common laborers. News of the Proclamation spread rapidly by word of mouth, arousing hopes of freedom, creating general confusion, and encouraging thousands to escape to Union lines. MORE

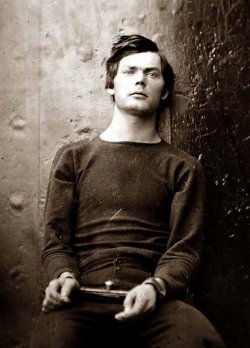

RELATED: Lincoln’s assassin, ambidextrous actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, had also ordered a fellow conspirator, Lewis Powell [pictured, left], to kill William H. Seward (then Secretary of State) and George Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson. Booth hoped to create chaos and overthrow the Federal government by assassinating Lincoln, Seward, and Johnson. Although Booth succeeded in killing Lincoln, the larger plot failed. Seward was attacked, but recovered from his wounds, and Johnson’s would-be assassin fled Washington, D.C. upon losing his nerve. MORE

RELATED: Lincoln’s assassin, ambidextrous actor and Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, had also ordered a fellow conspirator, Lewis Powell [pictured, left], to kill William H. Seward (then Secretary of State) and George Atzerodt to kill Vice President Andrew Johnson. Booth hoped to create chaos and overthrow the Federal government by assassinating Lincoln, Seward, and Johnson. Although Booth succeeded in killing Lincoln, the larger plot failed. Seward was attacked, but recovered from his wounds, and Johnson’s would-be assassin fled Washington, D.C. upon losing his nerve. MORE

HISTORY CHANNEL: Before Lincoln finally came to rest in a steel-and-concrete-reinforced underground vault in Springfield, the President’s body was repeatedly exhumed and moved, his coffin frequently opened. In 1876, eleven years after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, a band of Chicago counterfeiters plotted to steal Lincoln’s body and hold it for ransom. Their plan was to demand $200,000 and the release of the gang’s master engraver, who was in prison in Illinois. The Secret Service — recently formed to deal with the country’s ballooning counterfeiting problem — infiltrated the gang with an informer. It also set in motion a cringe-inducing chain of events in which a group of well-intentioned, self-appointed guardians took it upon themselves to protect Lincoln’s remains by any means necessary. This strange story of Lincoln at un-rest reveals how important this man was to so many, and perhaps our reluctance to let such a beloved and visionary leader go. MORE

BOSTON HERALD: You rarely see historians fighting off giggles in a documentary. But then, few things are as audacious as the plot to steal Abraham Lincoln’s body. In honor of Presidents Day and the 200th birthday of the 16th and perhaps most beloved president of all time, History unlocks a strange secret in our nation’s past in “Stealing  Lincoln’s Body” (tonight at 9 on the History Channel). In 1876, a group of Chicago counterfeiters planned to break into the rural Illinois cemetery where Lincoln’s remains were interred, steal the body and ransom it for $200,000 and the release of their chief engraver, then imprisoned. These weren’t exactly criminal masterminds. The men came this close. They broke into the tomb, fractured the sarcophagus and managed to pull the lead-lined, 500-pound coffin partly out of its container. The attempt at grave-robbing, however, shocked many. “It was like breaking in and taking the body of a saint,” one historian says. The incident spurred the creation of a secret society known as the Lincoln Guard of Honor. Lincoln’s remains were quietly moved to a basement and covered in a woodpile. His coffin would be moved several more times in the ensuing years. The public was never told. “Stealing Lincoln’s Body” is more than just a look at a bizarre crime. The two-hour production considers not only Lincoln’s assassination but the prolonged national period of mourning that followed. His death changed funeral practices and encouraged the use of embalming. Although Lincoln died in 1865, he did not reach a final resting place until 1901. Historians note here the irony that his remains were far more protected than the man ever was in life. MORE

Lincoln’s Body” (tonight at 9 on the History Channel). In 1876, a group of Chicago counterfeiters planned to break into the rural Illinois cemetery where Lincoln’s remains were interred, steal the body and ransom it for $200,000 and the release of their chief engraver, then imprisoned. These weren’t exactly criminal masterminds. The men came this close. They broke into the tomb, fractured the sarcophagus and managed to pull the lead-lined, 500-pound coffin partly out of its container. The attempt at grave-robbing, however, shocked many. “It was like breaking in and taking the body of a saint,” one historian says. The incident spurred the creation of a secret society known as the Lincoln Guard of Honor. Lincoln’s remains were quietly moved to a basement and covered in a woodpile. His coffin would be moved several more times in the ensuing years. The public was never told. “Stealing Lincoln’s Body” is more than just a look at a bizarre crime. The two-hour production considers not only Lincoln’s assassination but the prolonged national period of mourning that followed. His death changed funeral practices and encouraged the use of embalming. Although Lincoln died in 1865, he did not reach a final resting place until 1901. Historians note here the irony that his remains were far more protected than the man ever was in life. MORE

MEMPHIS FLYER: Hobbled by his injured leg, John Wilkes Booth was unable to get far. On April 26th, federal troops cornered the two men in a barn near Fredericksburg, Virginia. When Booth and Herold refused to surrender, the barn was set afire. Herold dashed out and was nabbed immediately, but Booth remained inside. Silhouetted against the flames, he was shot in the neck by a soldier firing (against orders) through a crack in the wall. Booth was dragged from the barn and died within minutes. His body was carried to Washington, D.C., where it was quickly  buried in a secret location at the federal penitentiary. Skeptics have always wondered why no autopsy was performed, why no family members or close friends were permitted to view the body, and — oddest of all — why the appearance of the corpse was so unlike that of John Wilkes Booth. Perhaps the Army realized that Booth had escaped after all.

buried in a secret location at the federal penitentiary. Skeptics have always wondered why no autopsy was performed, why no family members or close friends were permitted to view the body, and — oddest of all — why the appearance of the corpse was so unlike that of John Wilkes Booth. Perhaps the Army realized that Booth had escaped after all.

Accounts of Booth mention his curly black hair, yet two citizens who saw the body at the farm described it as red-haired. According to some reports, Herold surprised his captors by asking them, “Who was that man in the barn with me? He told me his name was Boyd.” And even though hundreds of people in Washington knew Booth well, no close friends were called to identify the remains. Instead, the Army relied on a few military men who had seen Booth on stage, along with the proprietor of a Washington hotel where Booth had lodged. As recounted in a 1944 issue of Harper’s, the strangest testimony came from Booth’s personal physician, who had once operated on Booth’s neck. When this man examined the body, he was stunned: “My surprise was so great that I at once said to [the surgeon general], ‘There is no resemblance in that corpse to Booth, nor can I believe it to be that of him.'”

That didn’t faze the surgeon general, who persuaded the doctor that a scar on the corpse’s neck was the result of the earlier operation. When the body was set upright, the doctor reluctantly admitted, “I was finally enabled to imperfectly recognize the features of Booth.” He was not entirely convinced, however: “But never in a human being had a greater change taken place.” Stories like these fueled rumors that John Wilkes Booth remained alive. His niece claimed that Booth had secretly met with her mother a year after the assassination and had lived on for another 37 years. A Maryland justice of the peace reported he ran into Booth in the 1870s. Many of these reports are surely preposterous. But one story cannot be dismissed so lightly. In 1872, a young lawyer who would later serve as assistant district attorney for Shelby County encountered a remarkable fellow in Texas. The lawyer’s name was Finis Langdon Bates. The strange man called himself John St. Helen. MORE

ABRAHAM LINCOLN: The Gettysburg Address

POETRYANIMATIONS: Heres a virtual movie of the 16th president of the United States Abraham Lincoln making The Gettysburg Address in Pennsylvania November 19, 1863. This most poetic of political speeches and lets face it most great politicians have the ability to wax lyrical is recited by the great linguist Harry E. Humphrey in this Edison sound recording circa 1913. MORE