BOSTON PHOENIX: In his bestselling autobiography, Dreams From My Father, President Obama introduces us to his high school friend, “Ray,” who, like him, is bi-racial. Who, also like him, is casting about to find his place in the world. But, who, unlike him, has a potty mouth that would make a sailor blush. Best of all? When reading the audiobook version of his bio, Obama does impressions of Ray’s manner of speech. Swear words and all. It’s fucking awesome. And it’s a way of talking we probably won’t be hearing from him now that he’s POTUS. Or will we? MORE

LISTEN: “You know that guy ain’t shit. Sorry-ass motherfucker ain’t got nothing on me.” (MP3)

LISTEN: “This shit’s getting way too complicated for me.” (MP3)

LISTEN: “There are white folks, and then there are ignorant motherfuckers like you.” (MP3)

LISTEN: “You ain’t my bitch, nigga! Buy your own damn fries!” (MP3)

LISTEN: “Sure you can have my number, baby!” (MP3)

***

PRESIDENT OBAMA SIGNS SCHIP: Ensuring Health Insurance of 11 Million Children

***

ANSWER: No, We Simply Cannot Have A Grown-Up Conversation About Marijuana

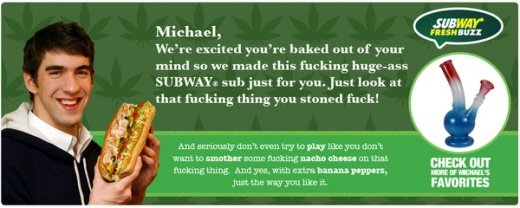

ASSOCIATED PRESS: Michael Phelps was suspended from competition for three months by USA Swimming, the latest fallout from a photo that showed the Olympic great inhaling from a marijuana pipe. The sport’s national governing body also cut off its financial support to Phelps for the same three-month period, effective Thursday.

“This is not a situation where any anti-doping rule was violated, but we decided to send a strong message to  Michael because he disappointed so many people, particularly the hundreds of thousands of USA Swimming member kids who look up to him as a role model and a hero,” the Colorado Springs-based federation said in a statement. “Michael has voluntarily accepted this reprimand and has committed to earn back our trust.”

Michael because he disappointed so many people, particularly the hundreds of thousands of USA Swimming member kids who look up to him as a role model and a hero,” the Colorado Springs-based federation said in a statement. “Michael has voluntarily accepted this reprimand and has committed to earn back our trust.”

Phelps won a record eight gold medals in Beijing and returned to America as one of the world’s most acclaimed athletes. Now he’s enduring a wave of bad news in the wake of the photo, published Sunday by News of the World, a British tabloid. Earlier Thursday, cereal and snack maker Kellogg Co. announced it wouldn’t renew its sponsorship contract with Phelps, saying his behavior is “not consistent with the image of Kellogg.” The swimmer appeared on the company’s cereal boxes after his Olympic triumph. MORE

BUZZNEWSROOM: Exclusive! Subway has officially de-linked Michael Phelps as they prepare to drop his recently announced sponsorship deal. Before Michael’s bong hits hit the headlines, Michael Phelps was featured on the Subway web site. However, since the swimmer’s pothead scandal, Subway has removed all links to pages featuring the Olympic swimmer. MORE

PREVIOUSLY: Now Can We Have A Grown-Up Conversation About Marijuana? Of Course, NOT!

PREVIOUSLY: The Reefer Madness Of American Pot Laws

Why Is Marijuana Illegal? Answer After The Jump

Why is Marijuana Illegal?

Shortcut Address:

http://marijuana.drugwarrant.com

A brief history of the criminalization of cannabis

| 7000-8000 B.C.

First woven fabric believed to be from hemp. 1619 Jamestown Colony, Virginia passes law requiring farmers to grow hemp. 1700s Hemp was the primary crop grown by George Washington at Mount Vernon, and a secondary crop grown by Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. 1884 Maine is the first state to outlaw alcohol. 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act is passed, forming the Food and Drug Administration. First time that drugs have any government oversight. 1913California, apparently, passes the first state marijuana law, though missed by many because it referred to “preparations of hemp, or loco weed.” 1914 Harrison Act passed, outlawing opiates and cocaine (taxing scheme) 1915 Utah passes state anti-marijuana law. 1919 18th Amendment to the Constitution (alcohol prohibition) is ratified. 1930 Harry J. Anslinger given control of the new Federal Bureau of Narcotics (he remains in the position until 1962) 1933 21st Amendment to the Constitution is ratified, repealing alcohol prohibition. 1937 Marijuana Tax Act 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act 1951 Boggs Amendment to the Harrison Narcotic Act (mandatory sentences) 1956 Narcotics Control Act adds more severe penalties 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act. Replaces and updates all previous laws concerning narcotics and other dangerous drugs. Empasis on law enforcement. Includes the Controlled Substances Act, where marijuana is classified a Schedule 1 drug (reserved for the most dangerous drugs that have no recognized medical use). 1972 Drug Abuse Office and Treatment Act. Establishes federally funded programs for prevention and treatment 1973 Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) Changes Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs into the DEA 1974 and 1978 Drug Abuse Treatment and Control Amendments. Extends 1972 act 1988 Anti-Drug Abuse Act. Establishes oversight office: National Office of Drug Control Policy and the Drug Czar 1992 ADAMHA Reorganization. Transfers NIDA, NIMH, and NIAAA to NIH and incorporates ADAMHA’s programs into the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) |

Many people assume that marijuana was made illegal through some kind of process involving scientific, medical, and government hearings; that it was to protect the citizens from what was determined to be a dangerous drug.The actual story shows a much different picture. Those who voted on the legal fate of this plant never had the facts, but were dependent on information supplied by those who had a specific agenda to deceive lawmakers. You’ll see below that the very first federal vote to prohibit marijuana was based entirely on a documented lie on the floor of the Senate.You’ll also see that the history of marijuana’s criminalization is filled with:

These are the actual reasons marijuana is illegal. Background For most of human history, marijuana has been completely legal. It’s not a recently discovered plant, nor is it a long-standing law. Marijuana has been illegal for less than 1% of the time that it’s been in use. Its known uses go back further than 7,000 B.C. and it was legal as recently as when Ronald Reagan was a boy. The marijuana (hemp) plant, of course, has an incredible number of uses. The earliest known woven fabric was apparently of hemp, and over the centuries the plant was used for food, incense, cloth, rope, and much more. This adds to some of the confusion over its introduction in the United States, as the plant was well known from the early 1600’s, but did not reach public awareness as a recreational drug until the early 1900’s. America’s first marijuana law was enacted at Jamestown Colony, Virginia in 1619. It was a law “ordering” all farmers to grow Indian hempseed. There were several other “must grow” laws over the next 200 years (you could be jailed for not growing hemp during times of shortage in Virginia between 1763 and 1767), and during most of that time, hemp was legal tender (you could even pay your taxes with hemp — try that today!) Hemp was such a critical crop for a number of purposes (including essential war requirements – rope, etc.) that the government went out of its way to encourage growth. The United States Census of 1850 counted 8,327 hemp “plantations” (minimum 2,000-acre farm) growing cannabis hemp for cloth, canvas and even the cordage used for baling cotton. The Mexican Connection In the early 1900s, the western states developed significant tensions regarding the influx of Mexican-Americans. The revolution in Mexico in 1910 spilled over the border, with General Pershing’s army clashing with bandit Pancho Villa. Later in that decade, bad feelings developed between the small farmer and the large farms that used cheaper Mexican labor. Then, the depression came and increased tensions, as jobs and welfare resources became scarce. One of the “differences” seized upon during this time was the fact that many Mexicans smoked marijuana and had brought the plant with them, and it was through this that California apparently passed the first state marijuana law, outlawing “preparations of hemp, or loco weed.” However, one of the first state laws outlawing marijuana may have been influenced, not just by Mexicans using the drug, but, oddly enough, because of Mormons using it. Mormons who traveled to Mexico in 1910 came back to Salt Lake City with marijuana. The church’s reaction to this may have contributed to the state’s marijuana law. (Note: the source for this speculation is from articles by Charles Whitebread, Professor of Law at USC Law School in a paper for the Virginia Law Review, and a speech to the California Judges Association (sourced below). Mormon blogger Ardis Parshall disputes this.) Other states quickly followed suit with marijuana prohibition laws, including Wyoming (1915), Texas (1919), Iowa (1923), Nevada (1923), Oregon (1923), Washington (1923), Arkansas (1923), and Nebraska (1927). These laws tended to be specifically targeted against the Mexican-American population. When Montana outlawed marijuana in 1927, the Butte Montana Standard reported a legislator’s comment: “When some beet field peon takes a few traces of this stuff… he thinks he has just been elected president of Mexico, so he starts out to execute all his political enemies.” In Texas, a senator said on the floor of the Senate: “All Mexicans are crazy, and this stuff [marijuana] is what makes them crazy.” Jazz and Assassins In the eastern states, the “problem” was attributed to a combination of Latin Americans and black jazz musicians. Marijuana and jazz traveled from New Orleans to Chicago, and then to Harlem, where marijuana became an indispensable part of the music scene, even entering the language of the black hits of the time (Louis Armstrong’s “Muggles”, Cab Calloway’s “That Funny Reefer Man”, Fats Waller’s “Viper’s Drag”). Again, racism was part of the charge against marijuana, as newspapers in 1934 editorialized: “Marihuana influences Negroes to look at white people in the eye, step on white men’s shadows and look at a white woman twice.” Two other fear-tactic rumors started to spread: one, that Mexicans, Blacks and other foreigners were snaring white children with marijuana; and two, the story of the “assassins.” Early stories of Marco Polo had told of “hasheesh-eaters” or hashashin, from which derived the term “assassin.” In the original stories, these professional killers were given large doses of hashish and brought to the ruler’s garden (to give them a glimpse of the paradise that awaited them upon successful completion of their mission). Then, after the effects of the drug disappeared, the assassin would fulfill his ruler’s wishes with cool, calculating loyalty. By the 1930s, the story had changed. Dr. A. E. Fossier wrote in the 1931 New Orleans Medical and Surgical Journal: “Under the influence of hashish those fanatics would madly rush at their enemies, and ruthlessly massacre every one within their grasp.” Within a very short time, marijuana started being linked to violent behavior. Alcohol Prohibition and Federal Approaches to Drug Prohibition During this time, the United States was also dealing with alcohol prohibition, which lasted from 1919 to 1933. Alcohol prohibition was extremely visible and debated at all levels, while drug laws were passed without the general public’s knowledge. National alcohol prohibition happened through the mechanism of an amendment to the constitution. Earlier (1914), the Harrison Act was passed, which provided federal tax penalties for opiates and cocaine. The federal approach is important. It was considered at the time that the federal government did not have the constitutional power to outlaw alcohol or drugs. It is because of this that alcohol prohibition required a constitutional amendment. At that time in our country’s history, the judiciary regularly placed the tenth amendment in the path of congressional regulation of “local” affairs, and direct regulation of medical practice was considered beyond congressional power under the commerce clause (since then, both provisions have been weakened so far as to have almost no meaning). Since drugs could not be outlawed at the federal level, the decision was made to use federal taxes as a way around the restriction. In the Harrison Act, legal uses of opiates and cocaine were taxed (supposedly as a revenue need by the federal government, which is the only way it would hold up in the courts), and those who didn’t follow the law found themselves in trouble with the treasury department. In 1930, a new division in the Treasury Department was established — the Federal Bureau of Narcotics — and Harry J. Anslinger was named director. This, if anything, marked the beginning of the all-out war against marijuana.

Anslinger was an extremely ambitious man, and he recognized the Bureau of Narcotics as an amazing career opportunity — a new government agency with the opportunity to define both the problem and the solution. He immediately realized that opiates and cocaine wouldn’t be enough to help build his agency, so he latched on to marijuana and started to work on making it illegal at the federal level. Anslinger immediately drew upon the themes of racism and violence to draw national attention to the problem he wanted to create. He also promoted and frequently read from “Gore Files” — wild reefer-madness-style exploitation tales of ax murderers on marijuana and sex and… Negroes. Here are some quotes that have been widely attributed to Anslinger and his Gore Files:

And he loved to pull out his own version of the “assassin” definition:

Harry Anslinger got some additional help from William Randolf Hearst, owner of a huge chain of newspapers. Hearst had lots of reasons to help. First, he hated Mexicans. Second, he had invested heavily in the timber industry to support his newspaper chain and didn’t want to see the development of hemp paper in competition. Third, he had lost 800,000 acres of timberland to Pancho Villa, so he hated Mexicans. Fourth, telling lurid lies about Mexicans (and the devil marijuana weed causing violence) sold newspapers, making him rich. Some samples from the San Francisco Examiner:

And other nationwide columns…

Hearst and Anslinger were then supported by Dupont chemical company and various pharmaceutical companies in the effort to outlaw cannabis. Dupont had patented nylon, and wanted hemp removed as competition. The pharmaceutical companies could neither identify nor standardize cannabis dosages, and besides, with cannabis, folks could grow their own medicine and not have to purchase it from large companies. This all set the stage for… The Marijuana Tax Act of 1937. After two years of secret planning, Anslinger brought his plan to Congress — complete with a scrapbook full of sensational Hearst editorials, stories of ax murderers who had supposedly smoked marijuana, and racial slurs. It was a remarkably short set of hearings. The one fly in Anslinger’s ointment was the appearance by Dr. William C. Woodward, Legislative Council of the American Medical Association. Woodward started by slamming Harry Anslinger and the Bureau of Narcotics for distorting earlier AMA statements that had nothing to do with marijuana and making them appear to be AMA endorsement for Anslinger’s view. He also reproached the legislature and the Bureau for using the term marijuana in the legislation and not publicizing it as a bill about cannabis or hemp. At this point, marijuana (or marihuana) was a sensationalist word used to refer to Mexicans smoking a drug and had not been connected in most people’s minds to the existing cannabis/hemp plant. Thus, many who had legitimate reasons to oppose the bill weren’t even aware of it. Woodward went on to state that the AMA was opposed to the legislation and further questioned the approach of the hearings, coming close to outright accusation of misconduct by Anslinger and the committee:

Committee members then proceeded to attack Dr. Woodward, questioning his motives in opposing the legislation. Even the Chairman joined in:

After some further bantering…

And that was basically it. Yellow journalism won over medical science. The committee passed the legislation on. And on the floor of the house, the entire discussion was:

And on the basis of that lie, on August 2, 1937, marijuana became illegal at the federal level. The entire coverage in the New York Times: “President Roosevelt signed today a bill to curb traffic in the narcotic, marihuana, through heavy taxes on transactions.” Anslinger as precursor to the Drug Czars Anslinger was essentially the first Drug Czar. Even though the term didn’t exist until William Bennett’s position as director of the White House Office of National Drug Policy, Anslinger acted in a similar fashion. In fact, there are some amazing parallels between Anslinger and the current Drug Czar John Walters. Both had kind of a carte blanche to go around demonizing drugs and drug users. Both had resources and a large public podium for their voice to be heard and to promote their personal agenda. Both lied constantly, often when it was unnecessary. Both were racists. Both had the ear of lawmakers, and both realized that they could persuade legislators and others based on lies, particularly if they could co-opt the media into squelching or downplaying any opposition views. Anslinger even had the ability to circumvent the First Amendment. He banned the Canadian movie “Drug Addict,” a 1946 documentary that realistically depicted the drug addicts and law enforcement efforts. He even tried to get Canada to ban the movie in their own country, or failing that, to prevent U.S. citizens from seeing the movie in Canada. Canada refused. (Today, Drug Czar John Walters is trying to bully Canada into keeping harsh marijuana laws.) Anslinger had 37 years to solidify the propaganda and stifle opposition. The lies continued the entire time (although the stories would adjust — the 21 year old Florida boy who killed his family of five got younger each time he told it). In 1961, he looked back at his efforts:

After Anslinger On a break from college in the 70s, I was visiting a church in rural Illinois. There in the literature racks in the back of the church was a lurid pamphlet about the evils of marijuana — all the old reefer madness propaganda about how it caused insanity and murder. I approached the minister and said “You can’t have this in your church. It’s all lies, and the church shouldn’t be about promoting lies.” Fortunately, my dad believed me, and he had the material removed. He didn’t even know how it got there. But without me speaking up, neither he nor the other members of the church had any reason NOT to believe what the pamphlet said. The propaganda machine had been that effective. The narrative since then has been a continual litany of:

… but that’s another whole story. MORE |

Harry J. Anslinger

Harry J. Anslinger Yellow Journalism

Yellow Journalism