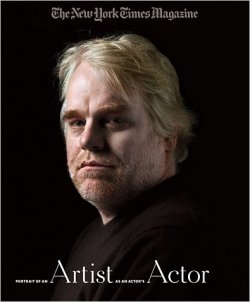

NEW YORK TIMES: WHEN HE WAS 12 YEARS OLD, PHILIP SEYMOUR HOFFMAN saw a local production of “All My Sons” near his home in Rochester, and it was, for him, one of those rare, life-altering events where, at an impressionable age, you catch a glimpse of another reality, a world that you never imagined possible. “I literally thought, I can’t believe this exists,” Hoffman told me on a gray day in London early in the fall. He was sitting in the fifth row of the audience at Trafalgar Studios in the West End, where he was directing “Riflemind” (a play about an ’80s rock band that may or may not reunite after 20 years), dressed in long brown cargo shorts, a stretched-out polo shirt and Converse sneakers without socks. His blond hair, still damp from showering, was standing in soft peaks on his head, which gave him the look of a very intense, newly hatched chick.

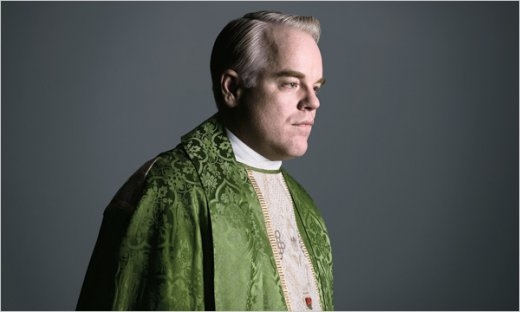

At times, especially when he is in or around or anywhere near a theater, Hoffman, who is 41, can seem like an eager college student — bounding from seat to stage to give direction, writing feverishly in a notebook about a feeling he wants an actor to convey, laughing at an in-joke regarding a prop that keeps disappearing — but when the conversation shifts to a discussion of his acting in movies like “Capote,” for which he deservedly won every award that’s been invented, or “Doubt,” out this month, he seems to turn inward and ages markedly. “The drama nerd comes out in me when I’m in a theater,” he  explained now, as the actors rehearsed. “When I saw ‘All My Sons,’ I was changed — permanently changed — by that experience. It was like a miracle to me. But that deep kind of love comes at a price: for me, acting is torturous, and it’s torturous because you know it’s a beautiful thing. I was young once, and I said, That’s beautiful and I want that. Wanting it is easy, but trying to be great — well, that’s absolutely torturous.”

explained now, as the actors rehearsed. “When I saw ‘All My Sons,’ I was changed — permanently changed — by that experience. It was like a miracle to me. But that deep kind of love comes at a price: for me, acting is torturous, and it’s torturous because you know it’s a beautiful thing. I was young once, and I said, That’s beautiful and I want that. Wanting it is easy, but trying to be great — well, that’s absolutely torturous.”

Hoffman took a gulp of coffee from a large cup that he was holding in a brown paper bag. He turned his attention to the stage, where two actors were rehearsing a sex scene. “Riflemind,” which unfolds over a weekend, is a self-conscious study in wounds: long-simmering battles are reignited and secrets are revealed. The play has a predictable middle-aged-angst narrative that is somewhat glamorized by its rock-star milieu: the drugs may be stronger, but the emotions are oddly detached. Hoffman’s fascination with “Riflemind” — he directed it in Sydney, Australia, last year and, when we met, had been in London for several weeks preparing this production — can be explained by both his commitment to theater and by the fact that the play is written by Andrew Upton, the husband of Cate Blanchett. Hoffman met Upton and Blanchett when he appeared with her in “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” “On that movie, we shot only one or two days a week,” Hoffman recalled. “Much of the time, I was in Rome with Cate and Andrew. I have a hard time having fun, but that was heaven. And I must really like Andrew — my girlfriend, who is in New York, is about to have our third child, and I am here.” Hoffman paused. “I don’t get nervous when I’m directing a play. It’s not like acting. If this fails, I wouldn’t be as upset by it.”

Hoffman jumped out of his seat and ran to the stage. He proceeded to correct the sex scene. He bent the actress back over a couch and metamorphosed into a desperate character, the former manager of the band, driven by the hope of sudden riches and his lust for the guitar player’s wife. He played just enough of the scene and, then, he switched back to being Phil, the regular guy in the baggy shorts. It was stunning. “I don’t know how he does it,” Mike Nichols, who has directed Hoffman on the stage (“The Seagull”) and in movies (“Charlie Wilson’s War”), told me later. “Again and again, he can truly become someone I’ve not seen before but can still instantly recognize. Sometimes Phil loses some weight, and he may dye his hair but, really, it’s just the same Phil, and yet, he’s never the same person from part to part. Last year, he did three films — ‘The Savages,’ ‘Charlie Wilson’s War’ and ‘Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead’ — and in each one he was a distinct and entirely different human. It’s that humanity that is so striking — when you watch Phil work, his entire constitution seems to change. He may look like Phil, but there’s something different in his eyes. And that means he’s reconstituted himself from within, willfully rearranging his molecules to become another human being.” MORE