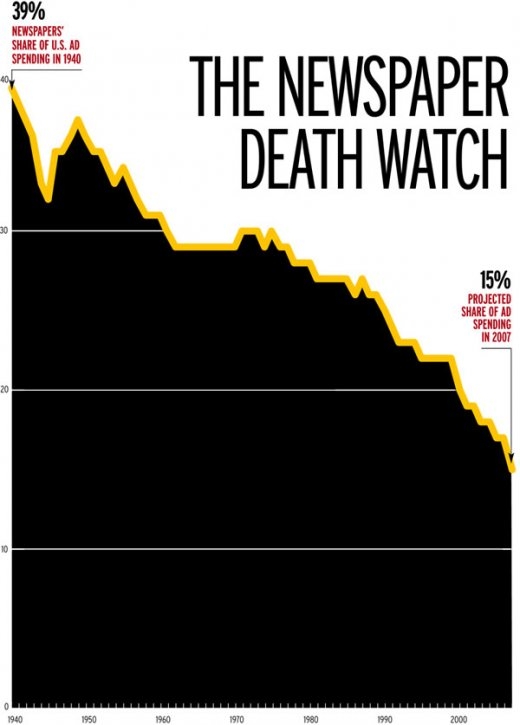

ASSOCIATED PRESS: U.S. newspaper advertising revenue collapsed by nearly $2 billion, or 18 percent, in the third quarter, according to the Newspaper Association of America, an industry group. Even online ad revenue made a small U-turn for the second quarter in a row. The year-on-year quarterly percentage decline is the worst since since the NAA has been keeping such records and represents an increasingly rapid deceleration that began in the third quarter of 2006, when total ad spending dropped 1.5 percent. The figures, updated on the day before Thanksgiving, show total ad spending at newspapers fell 18.1 percent to $8.94 billion, down from $10.92 billion in the third quarter last year. The last time total quarterly ad spending fell below $9 billion was in the first quarter of 1996. Print ad revenue dropped 19.3 percent to $8.19 billion from $10.15 billion. Online ad revenue fell 3 percent to $749.8 million from $773.0 million a year ago _ a remarkable turnaround since the steady double-digit growth from 2004 to 2007. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: The talk of newspapers’ demise is older than some of the reporters who write about it, but what is happening now is something new, something more serious than anyone has experienced in generations. Last year started badly and ended worse, with shrinking profits and tumbling stock prices, and 2008 is shaping up as more  of the same, prompting louder talk about a dark turning point.

of the same, prompting louder talk about a dark turning point.

“I’m an optimist, but it is very hard to be positive about what’s going on,” said Brian P. Tierney, publisher of The Philadelphia Inquirer and The Philadelphia Daily News. “The next few years are transitional, and I think some papers aren’t going to make it.” Circulation revenue has declined steadily since 2003, and the number of copies sold has been slipping about 2 percent a year. Some of the largest papers — including The San Francisco Chronicle, The Boston Globe and The Los Angeles Times — have lost 20 to 30 percent of their circulation in just a few years.

The paradox is that more people than ever read newspapers, now that some major papers have several times as many readers online as in print. And papers sell more ads than ever, when online ads are included. But for every dollar advertisers pay to reach a print reader, they pay about 5 cents, on average, to reach an Internet reader. Newspapers need to narrow that gap, but the rise in Internet revenue slowed sharply last year. MORE

ROGUE COLUMNIST: We hear endlessly that the troubles are a result of the Internet, new technology, “people don’t read anymore,” and, my favorite, “people don’t have as much time as they used to.” As if there was once a 36-hour day, or people who once worked 12-hour shifts while raising large families had this abundance of time. These forces are real. And yes, a big swath of the public is distracted by celebrity gossip and gets its “news” from blogs, television and talk radio. What’s less noted is how newspapers themselves contributed to the dumbing down of America. What’s most frustrating is that the discussion fails to focus on the more significant reasons behind the  decline in newspaper journalism. They are…

decline in newspaper journalism. They are…

- Groupthink was a natural outgrowth of monopolies and the demands of Wall Street. This was hastened by the ascendancy of Gannett and its (for a while) superior returns. A startlingly conformist agenda emerged all over: design over content; short, uninteresting (but non-irritating to advertisers) stories, etc. The universe of different tactics, strategies and innovations that a competitive industry would have evolved never happened. The industry became strikingly inwardly focused, insulated from a changing world. When change was noted, it somehow always produced moves that degraded the news product. Years were spent developing “new editorial products” to attract non-readers. This was a questionable use of resources, as surveys and focus groups showed most of these people wouldn’t read anyway, and certainly not subscribe seven days a week to a print edition. But the resources to do them were diverted away from coverage that served existing readers. Industry leaders were singularly cavalier about their loyal customers, while chasing ones they had little chance to attracting.

- Leadership collapsed under the weight of these forces. A generation of managers that would go along with these dictates rose, while those with other ideas were pushed out or aside. These surviving managers – of course with honorable exceptions – were singularly incapable of dealing with the historic turning points facing newspapers. Every day they came in hoping to not make a mistake, to merely preserve the business they had, or to push through artificial, top-down, one-side-fits-all formulas, usually backed by questionable research. At some chains, the jobs of editors became little more than gathering stuff for graphic do-dads and implementing the content rules cooked up at

headquarters. These were once the front-line leaders who made the biggest difference in the quality of a product based, inexorably, on the written word, well told. The simple creed of “get a great story and put it in the newspaper (or online)” went away. For example, experienced police reporters went away — even though it’s clear that well-done cop stories draw readers. In their place was a 21-year-old taking dictation from a police public-affairs announcement. MORE

headquarters. These were once the front-line leaders who made the biggest difference in the quality of a product based, inexorably, on the written word, well told. The simple creed of “get a great story and put it in the newspaper (or online)” went away. For example, experienced police reporters went away — even though it’s clear that well-done cop stories draw readers. In their place was a 21-year-old taking dictation from a police public-affairs announcement. MORE