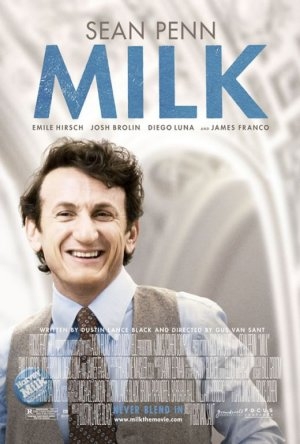

MILK (2008, directed by Gus Van Sant, 128 minutes, U.S.)

MILK (2008, directed by Gus Van Sant, 128 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK, FILM CRITIC

Just last month Josh Brolin starred in W, the Oliver Stone biopic, utterly inhabiting the the dim, destructive id of incurious-ness. Now a month later Brolin pops up as the dark id of intolerance, political assassin Dan White in Gus Van Sant’s Milk. Where W seemed designed to hammer a stake into the heart of Bush’s legacy, Milk, which chronicles the life of slain gay activist Harvey Milk, uses the past as a map to inspire the future’s possibilities. If Stone’s film was dismissed in some quarters as yesterday’s news, Milk’s history couldn’t be more alive and relevant, especially with the recent passing of California’s anti-gay marriage Proposition 8 which galvanized gay activism across the nation.

A Big Picture film that never loses its sense of intimacy, Milk recreates the world of 1970’s San Francisco down to the last post-counter-cultural detail. Despite the city’s storied embrace of alternative lifestyles, the city’s large gay population remains largely invisible, since evidence of homosexuality is a legally permissible reason for job dismissal. When we meet Harvey he is a still-closeted insurance salesman cruising the subway and seducing a young hippie fellow named Scott (James Franco) to help him celebrate his birthday. Like Bush, Harvey hits forty knowing he’s been an underachiever (“I’m forty years old and I’ve done nothing with my life” he confides after sex), with only the vaguest idea of what he wants to do. Together Scott and Harvey open a camera shop in the Castro and the harassment he witnesses there inspires Milk to run for city council as the first openly gay candidate.

Initially, San Francisco proves unready for this radical change and Harvey fails in his bid for that seat, but Harvey (much like our President-elect) discovers his power is in community organizing. Van Sant maintains a bit of the naturalism he has brought to his recent less-commercial projects (Paranoid Park, Elephant etc.) to give Harvey’s tireless activism a freewheeling sense of reality, keeping the film from falling into the plodding and episodic predictability that sinks so many biopics. While Harvey’s destiny as a martyr is revealed in the opening scenes, Milk’s unforced narrative never seems like it is headed to a foregone conclusion.

The unmannered style Van Sant uses here perfectly compliments Sean Penn’s magnetic performance, a dead-on  and instinctual piece of film acting sure to be remembered as one of his career highlights. Entering middle age, Penn has shown a tendency in recent years to chomp the scenery, falling prey to the same kind of overstatement that has marred Al Pacino’s legacy in recent years. That’s not the case here: despite playing a flamboyant gay man with a thick Long Island accent, Penn captures Milk’s ego and his sense of the theatrical without upstaging his co-stars. Among the co-stars who make the biggest impression is the on-a-roll Brolin, who quietly underplays the deadly pathology boiling beneath the wrapped-to-tight demeanor of Dan White.

and instinctual piece of film acting sure to be remembered as one of his career highlights. Entering middle age, Penn has shown a tendency in recent years to chomp the scenery, falling prey to the same kind of overstatement that has marred Al Pacino’s legacy in recent years. That’s not the case here: despite playing a flamboyant gay man with a thick Long Island accent, Penn captures Milk’s ego and his sense of the theatrical without upstaging his co-stars. Among the co-stars who make the biggest impression is the on-a-roll Brolin, who quietly underplays the deadly pathology boiling beneath the wrapped-to-tight demeanor of Dan White.

Even though great care is taken to evoke a lived-in 1970’s world, what is being fought for in Milk does not seem like a battle won long ago. What they are striving for is part of the same fight represented by Proposition 8, the battle for people in a minority to share the same rights enjoyed by the majority. While Van Sant works in a little of Puccini’s Tosca to underline the final tragedy, he wisely stays away from lionizing Harvey as a martyr, keeping him on a resolutely human scale. “You’ve got to give them hope” is the last thing we hear from Penn’s Harvey utter, a statement that recent history has given a contemporary ring and a legacy Harvey would undoubtedly endorse.