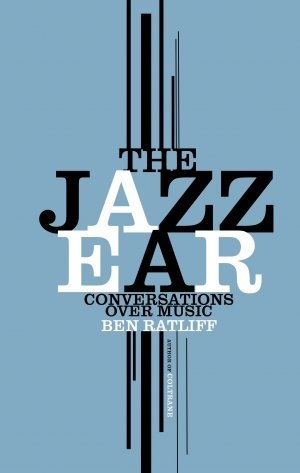

BY DAVE ALLEN Ben Ratliff has been the jazz critic for the New York Times since 1996. His reviews of live performances – produced at a rate of nearly one per night, always with a keen ear and a sharp word – always aim for the heart of the sound, and his newest book, The Jazz Ear: Conversations Over Music, strikes out for the same territory by a different path: through the words of the players themselves. He’ll be in Philadelphia tonight for a “conversation over music” with pianist Orrin Evans, an adoptive Philadelphian who’s made an impact on Ratliff’s home turf.

BY DAVE ALLEN Ben Ratliff has been the jazz critic for the New York Times since 1996. His reviews of live performances – produced at a rate of nearly one per night, always with a keen ear and a sharp word – always aim for the heart of the sound, and his newest book, The Jazz Ear: Conversations Over Music, strikes out for the same territory by a different path: through the words of the players themselves. He’ll be in Philadelphia tonight for a “conversation over music” with pianist Orrin Evans, an adoptive Philadelphian who’s made an impact on Ratliff’s home turf.

PHAWKER: Going into these conversations, are you ever worried that one or both of you might clam up – that you might step on one another’s toes or cross some uncrossable line? How did you keep that from happening?

BEN RATLIFF: Nah, we’re all grownups, doing the best we can out here, and in some cases the musicians seem relieved to talk not about their new albums, but about bigger ideas that have been lurking deep inside them. Jazz musicians, categorically, are fairly deep on what they do. And in the absence of mass adulation and the problem of how to furnish their third house, I think they have some time to think about more basic questions, like what music is for.

PHAWKER: On the other hand, does it ever get too wild or tangential? At what point would you have to rein someone in and say “So, back to the piece…”

BEN RATLIFF: Yes. Early on, my editor called these pieces “Smoking pot with Ratliff.” After that, it became a point of pride with me to push the conversations as far out as possible. (With some people this is hard; with others this is very easy.) Then you edit, or you do what you have to do so that the logic seems trackable. That can’t happen on tour, in front of audiences–too boring. But good things can come from long, woolly conversations, if you have some time to squeeze the juice out. There is no substitute for knowing where the musician is coming from, but I don’t believe that one always has to ask the perfect question. Sometimes a dumb question, badly phrased, can start a good volley. The conversations did get pretty far out there, especially with Wayne Shorter and Ornette Coleman. But a journalist becomes used to bringing someone back to the piece, no matter what it’s about.

PHAWKER: How did you get hooked up with Evans for this event? We know he can play, but what made you think he’d have something to say?

BEN RATLIFF: I’ve known Orrin for ten years, since I was stunned by him at a gig in New York. He can play, yes. He’s also a good spieler. He’s provocative, and he likes to talk about how to connect with audiences, how to get the message out there.

PHAWKER: For many fans of pop or rock music, their model for how to listen to music comes from the early critics like Lester Bangs, or perhaps from Rob Gordon in High Fidelity. What do you think those fans could learn from the way jazz musicians listen?

BEN RATLIFF: The phrase “jazz snob” is common parlance, but jazz musicians tend not to be snobs. In fact they  tend to be almost crazily open-minded. Jazz is a jumping-off place to enter into practically any kind of music in the world. Perhaps for this reason its musicians listen to just about everything. If it isn’t compositionally interesting, they’re curious about the performer’s stagecraft. If the stagecraft is non-existent, they’re interested in the audience. Et cetera. A lot of jazz musicians have the disoriented affect of those who have just been pulled away from focusing for hours on something extremely complicated and stimulating. You know why they seem like that? Because that’s exactly what they have been doing. And yet by and large they’re not grouchy about what they’re being asked to look at or listen to: they have been trained to believe that they can use it some way. They also–the best of them, anyway–have the best possible sense of humor: inventive and absurd and sentimental.

tend to be almost crazily open-minded. Jazz is a jumping-off place to enter into practically any kind of music in the world. Perhaps for this reason its musicians listen to just about everything. If it isn’t compositionally interesting, they’re curious about the performer’s stagecraft. If the stagecraft is non-existent, they’re interested in the audience. Et cetera. A lot of jazz musicians have the disoriented affect of those who have just been pulled away from focusing for hours on something extremely complicated and stimulating. You know why they seem like that? Because that’s exactly what they have been doing. And yet by and large they’re not grouchy about what they’re being asked to look at or listen to: they have been trained to believe that they can use it some way. They also–the best of them, anyway–have the best possible sense of humor: inventive and absurd and sentimental.

PHAWKER: How and why did you get started in criticism? What was your path to ending up at the New York Times?

BEN RATLIFF: I started listening to jazz in serious way when I was around 17 and I had a college radio-station record-library to help me. I just connected one thing to another, worked my way backwards, and found that there was more there than I could ever know. Since I wasn’t a student of history and wasn’t in training to write fiction, Jazz criticism, at the time–the late 80s–seemed to me like a better lens for understanding 20th century culture than what was available to me otherwise. What turned me on wasn’t the idea of giving out grades and consumer reports, but connecting the artist with the society around him. I wrote for little magazines, and then for the Village Voice, and then there was an opening at the Times. Once I was doing it for a living, I found that what I really wanted, ideally and at best, was to try through writing to make music seem sort of physical or tangible. I’m not someone who hears the key of D and sees yellow, but there’s something to be learned from that neurological condition: how to describe music as if it were something beautiful, sitting there in front of you. It defies reason, but so does the power of music.

PHAWKER: How do you see the intended audience for The Jazz Ear? Is it for jazz devotees who want to know how the legends really think? Or is it more for newcomers, as a resource to decode or demystify the music?

BEN RATLIFF: As objectively brilliant as Wayne Shorter or Maria Schneider or Paul Motian might be, I think lots of average listeners hear music in their own inspired ways. I’m just trying to connect the act of listening between the artist and the reader. I also think that writing about artists has hardened into journalistic forms–the review, the profile, the process piece–and I wanted to get around that.

[Author photo by KATE FOX-REYNOLDS]