NEW YORK TIMES: ON first viewing, the comedy sketches on “Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!” can seem like outtakes from a public-access channel that’s broadcast only in hell. They are full of shoddily produced, sloppily edited talk shows about acne and commercials for utterly unnecessary gadgets, and populated by people who should never stand within 50 feet of a camera lens. When these elements appear in a typical television program, they’re usually a result of accidents, budgetary restrictions and bad choices. When they appear on “Awesome Show,” they’re intentional.

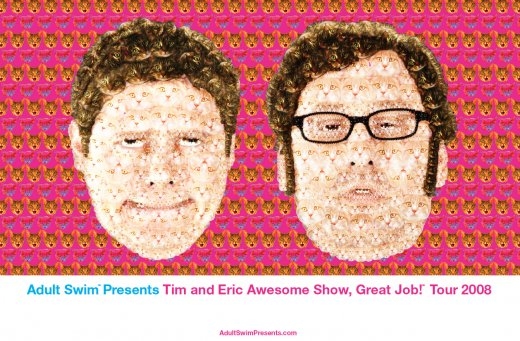

“We have a very strict set of rules of what we think is funny,” said Eric Wareheim, who created and stars in the series with Tim Heidecker. “And,” Mr. Heidecker added, “I guess those would be, in no particular order: darkness, discomfort, confusion and things that shouldn’t exist.” Lovingly described by its architects as “the nightmare version of television,” “Awesome Show” (which returns to the Cartoon Network’s after-hours Adult Swim lineup Sunday night for its third season) revels in an aesthetic of awkwardness. It favors quick sketches about pathetic office workers and desperate on-air pitchmen, and music videos for scatological songs. It elevates people recruited from the streets of Los Angeles to the status of celebrities and treats the celebrities who appear on the show as unwanted extras.

Swim lineup Sunday night for its third season) revels in an aesthetic of awkwardness. It favors quick sketches about pathetic office workers and desperate on-air pitchmen, and music videos for scatological songs. It elevates people recruited from the streets of Los Angeles to the status of celebrities and treats the celebrities who appear on the show as unwanted extras.

Since meeting as film students at Temple University in the 1990s, Mr. Heidecker and Mr. Wareheim, both 32-year-old Pennsylvania natives, have noticed that their comedic sensibilities differed greatly from societal norms. At college they created short films that anticipated their “Awesome Show” milieu — e.g., a sloppily edited promotional trailer for a cat film festival — and eventually grew brave enough to send their reel (and an invoice for $50) to the comedian Bob Odenkirk, the co-creator of the influential sketch series “Mr. Show With Bob and David.” Mr. Odenkirk did not pay the enclosed bill, but he enjoyed Mr. Wareheim and Mr. Heidecker’s shorts enough to become their mentor. “My first question to them was, ‘What scene are you in?’” Mr. Odenkirk recalled in an interview. “I thought maybe they knew everyone in New York and played their films in the clubs. And they were like, ‘What are you talking about?’” “It occurred to me,” Mr. Odenkirk added, “that they aren’t being influenced by anybody. They’re in their own little world, and that’s why they’ve gotten good at this.”