ASSOCIATED PRESS: SEOUL, South Korea — South Korea’s president said Wednesday that his government will make a fresh start, hours after an estimated 80,000 people gathered in the South Korean capital in the largest demonstration yet against the planned resumption of U.S. beef imports. The government agreed in April to lift almost all restrictions that had been imposed on imports of U.S. beef over fears of mad cow disease. Opponents of the plan worry it does not do enough to protect citizens. Lee, a pro-American conservative, agreed in April just before a summit with President Bush to reopen the country’s beef market — resolving the issue that had long been an irritant in bilateral ties. South Korea was the third-largest overseas customer for U.S. beef until it banned imports after a case of mad cow disease — the first of three confirmed in the U.S. — was detected in 2003. MORE

ASSOCIATED PRESS: SEOUL, South Korea — South Korea’s president said Wednesday that his government will make a fresh start, hours after an estimated 80,000 people gathered in the South Korean capital in the largest demonstration yet against the planned resumption of U.S. beef imports. The government agreed in April to lift almost all restrictions that had been imposed on imports of U.S. beef over fears of mad cow disease. Opponents of the plan worry it does not do enough to protect citizens. Lee, a pro-American conservative, agreed in April just before a summit with President Bush to reopen the country’s beef market — resolving the issue that had long been an irritant in bilateral ties. South Korea was the third-largest overseas customer for U.S. beef until it banned imports after a case of mad cow disease — the first of three confirmed in the U.S. — was detected in 2003. MORE

NEW YORK TIMES: About 50 countries, including Korea, Taiwan and Japan the last of which accounted for 36 percent of American beef exports closed their doors to American beef after the first confirmed case of mad cow disease was found in Moses Lake, Wash., in December 2003. The circumstances of that first case, and the defensive reactions of the United States Department of Agriculture after its discovery, led to years of skepticism by American consumer groups and difficult negotiations with foreign countries over reopening their markets — especially in Asia’s wealthier countries, where consumers are used to demanding that their governments certify that imported food is safe.

Although the first infected cow was probably not a “downer” — too diseased or crippled to walk — it was part of a shipment of broken-down old dairy cows, and it became clear from press reports that some small slaughterhouses specialized in taking such borderline animals, which often had to be hoisted or winched out of their trucks on chains. Also, by the time the test results came back two weeks after the cow was killed, it had already been ground into hamburger, mixed with 10,000 pounds of meat from other animals and shipped to supermarkets. Despite a multi-state recall, experts conceded that much had undoubtedly been cooked and eaten. The cow’s spinal cord — likely to contain the most infectious material — had been sent to a plant that made food for pets and pigs.

In the wake of the first case, the Agriculture Department issued assurances that American beef was safe. Although most Americans did not stop buying beef, foreign customers were openly skeptical, for several reasons. The chief one was that the United States was testing only a tiny fraction of the 30 million animals it slaughtered each year. In 1997, the year it banned feeding ruminant protein to other ruminants because of the suspicions about the disease in Europe, it tested only 219 animals. In 2003, when the first positive was found, it was testing about 20,000 a year.

most Americans did not stop buying beef, foreign customers were openly skeptical, for several reasons. The chief one was that the United States was testing only a tiny fraction of the 30 million animals it slaughtered each year. In 1997, the year it banned feeding ruminant protein to other ruminants because of the suspicions about the disease in Europe, it tested only 219 animals. In 2003, when the first positive was found, it was testing about 20,000 a year.

At the time, European countries were testing 10 million animals annually, and the Japanese were testing every one of the 1.2 million they slaughtered. Even after the first case was found, the department initially resisted increased its testing, and then raised it to only about 40,000 animals a year. Department officials explained that their testing was only for surveillance, not food safety.

There were other suspicions about its motives. Many other countries have food safety agencies that are separate from their agriculture departments, which exist primarily to help farmers and increase farm sales. In the United States, however, the Agriculture Department, not the Food and Drug Administration, certifies meat as safe. The secretary of agriculture at the time, Ann M. Veneman, was a former food industry lobbyist and her spokeswoman had previously been the chief spokeswoman for the beef lobby. MORE

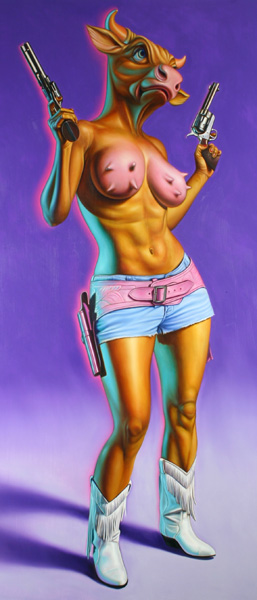

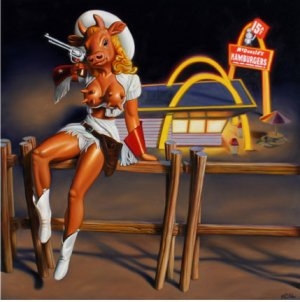

[Artwork by RON ENGLISH]