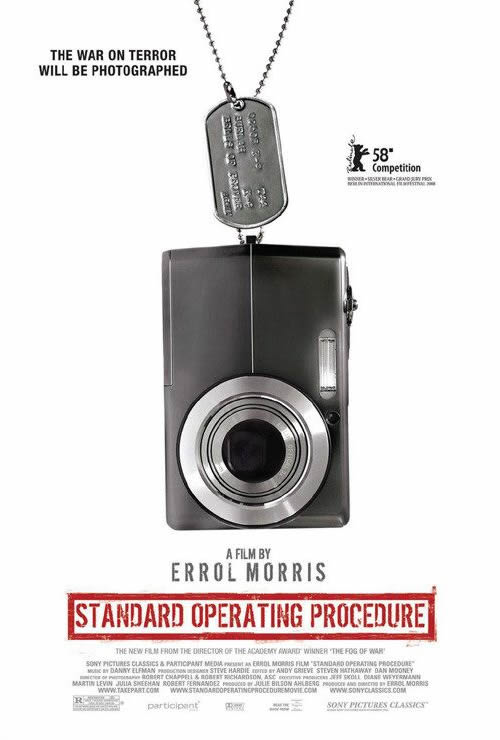

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE (2008, directed by Errol Morris, 118 minutes, U.S.) BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC He sure has come a long way since pondering why people bury their critters in pet cemeteries. Esteemed documentarian Errol Morris may have started out with whimsical examinations of the American psyche, but as his career has progressed his subject matter has gained gravitas, culminating in 2003’s Fog of War, a profile of Vietnam War architect Robert McNamara. Although the events covered in Fog of War were 40 years old Morris, was able to concentrate on the disturbing reality of executing a war in a manner which underlined its modern relevance. With Standard Operating Procedure, Morris jumps out of the frying pan and into the fire, recreating the state-of-the-art House of Horrors the U.S. unleashed in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison. “Deeply disturbing” does not begin to describe what he finds. Even if you are familiar with the gruesome facts of the torture that took place there, Standard Operating Procedure takes you closer to the heart of darkness than any other study of this American atrocity.

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC He sure has come a long way since pondering why people bury their critters in pet cemeteries. Esteemed documentarian Errol Morris may have started out with whimsical examinations of the American psyche, but as his career has progressed his subject matter has gained gravitas, culminating in 2003’s Fog of War, a profile of Vietnam War architect Robert McNamara. Although the events covered in Fog of War were 40 years old Morris, was able to concentrate on the disturbing reality of executing a war in a manner which underlined its modern relevance. With Standard Operating Procedure, Morris jumps out of the frying pan and into the fire, recreating the state-of-the-art House of Horrors the U.S. unleashed in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison. “Deeply disturbing” does not begin to describe what he finds. Even if you are familiar with the gruesome facts of the torture that took place there, Standard Operating Procedure takes you closer to the heart of darkness than any other study of this American atrocity.

Working for the first time with a current news story, Morris bring us a tale that nearly everyone will come to with preconceptions. Laying mine on the table, I suspected that the film would reveal how the military command structure and the stresses of life at the battlefront made such inhuman treatment unavoidable. I expected to have some hard-won sympathy for the soldiers, who had been forced by circumstance to commit acts that they never would have dreamed of otherwise. I expected tearful penance.

I think I would have found this almost comforting, reassuring me that people were basically “good.” Faced again with those sickening photographs, this time projected large and intermixed with photos of the jolly everyday camaraderie of the participants, I was shocked that I ever thought a lesson of the goodness of our souls was at the heart of this story.

Morris has rounded up almost all of the American stars of those photos, front and center being the women of Abu Ghraib: mousy Lynndie England, sweet-smiling Sabrina Harman and big-boned Megan Ambuhl. Each stares into the eyes of Errol Morris’ Interrotron and tells their side of the story, and what we see is more Lizzie Borden than Girl Next Door. They each tell their story with a barely suppressed sigh, like they were being punished for some meaningless infraction. They occasionally let out a stifled laugh at the surreal quality of the scenes they saw, and each guffaw sends chills. And each has a transparent alibi: it was love, or they were on the periphery, or, in Sabrina Harman’s case, that she privately disagreed left her inculpable of any crime. None expresses more than a passing thought to the humanity, the real people, who flailed at their feet. Morris’ film gives them the respect to tell their stories in a dignified setting but whether it was the things they’ve seen or the things they’ve done, as they stand today they seem as unknowable as the women of the Manson Family.

Not that the men fare any better. To a man, they act aggrieved that their stay at Abu Ghraib has ruined their lives and reputation, without acknowledging what effect their actions might have had on their prisoners. This, despite the fact that everyone seems aware that these round-ups were full of innocent people. “I’m a nice guy,” one of soldiers says in disbelief, despite documentation revealing how expansive he is with the term “nice guy.” I’m broad-minded enough to consider that in many ways the soldiers are victims as well, but it is pretty nauseating to hear them make the proclamation without sensing any remorse that they might have for those they have hog-tied.

Notably missing from the film is the mustachioed Charles Graner, whom the government is not allowing to be interviewed while he serves out his 10-year sentence. Circumstances make it appear as if ringleader Graner was the liaison between the torturers and their government supervisors, and his absence is frustrating to those who might want to see this damning documentary point its accusatory finger higher (former defense secretary Rumsfeld shows up early for a limited tour of the prison, avoiding the interrogation cell like a guy who loves steak but can’t bear the sight of the slaughterhouse). Still, I understand Morris’ decision to limit the film’s focus; the Bush Administration’s reserved, rhetorical “outrage” at the public discovery of their torture chamber should have been damning enough.