[Photo by TIFFANY YOON]

By Peter Nicholas, Los Angeles Times Staff Writer

PHILADELPHIA — Hal Sawyer figures he knows just what is needed to deliver his precinct for Barack Obama in the gritty world of Philadelphia politics. He has rigged up his Dodge Caravan with a loudspeaker so he can drive through his neighborhood in northwest Philadelphia urging people to come out to Obama events. He has reams of contacts as a local committeeman, part of the city’s entrenched Democratic Party machine.So when Sawyer walked into an Obama campaign office and asked for a yard sign, the response took him aback. They said they didn’t have any. “Then I tried to play the ‘I’m a Democratic committeeman’ card and ‘I need materials for my voters and stuff for election day.’ And their response was nothing, zero. ‘You’re a what?'” The mutual puzzlement underscores the culture clash within the coalition working to elect Obama here. In the run-up to the Pennsylvania primary Tuesday, there is a deep divide over the best tactics to use in this city’s quirky political culture.

PHILADELPHIA — Hal Sawyer figures he knows just what is needed to deliver his precinct for Barack Obama in the gritty world of Philadelphia politics. He has rigged up his Dodge Caravan with a loudspeaker so he can drive through his neighborhood in northwest Philadelphia urging people to come out to Obama events. He has reams of contacts as a local committeeman, part of the city’s entrenched Democratic Party machine.So when Sawyer walked into an Obama campaign office and asked for a yard sign, the response took him aback. They said they didn’t have any. “Then I tried to play the ‘I’m a Democratic committeeman’ card and ‘I need materials for my voters and stuff for election day.’ And their response was nothing, zero. ‘You’re a what?'” The mutual puzzlement underscores the culture clash within the coalition working to elect Obama here. In the run-up to the Pennsylvania primary Tuesday, there is a deep divide over the best tactics to use in this city’s quirky political culture.

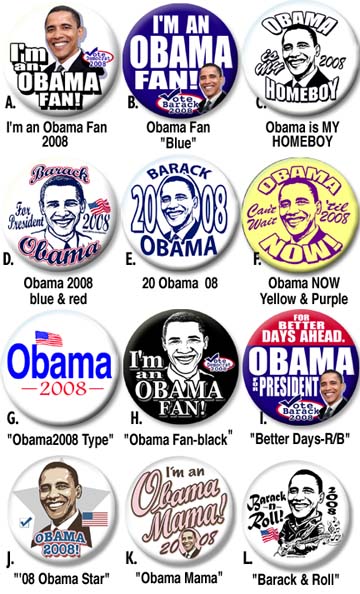

On one side is the city’s aging Democratic apparatus, a collection of pro-Obama ward leaders and committee people whose tools of persuasion are yard signs, campaign hats, buttons, stickers and “street money” — cash handed out before the election to juice turnout. On the other is the Obama campaign team, a network of young aides from out of state who eschew the traditional trappings of a campaign and think that elections turn on intangibles: grass-roots organization and an ever-expanding web of volunteers motivated by a deep belief in the candidate.

The Obama camp isn’t bent on planting signs in every yard. Nor is it paying street money to party bosses in hopes that they’ll get people to the polls. Instead, the campaign wants to build an efficient and more loyal apparatus by enlisting volunteers who have one agenda: an Obama victory.

One hot spot in this uneasy alliance is a stretch of northwest Philadelphia that includes a section known as Germantown. The area spans two wards and is home to 29,000 registered Democratic voters — about 4% of the citywide total. A diverse part of the city, the neighborhood includes grand 19th century Victorian houses and abandoned row homes.

The Obama campaign is betting that its get-out-the-vote operation, and the theory that underpins it, will prevail even in an older city like Philadelphia that still practices machine politics. But the political leadership here is watching with dismay and growing resentment. “They have paid college kids coming to our community and trying to get us to volunteer — for them, not with them,” said Greg Paulmier, 49, the neighborhood ward leader for the last 14 years. “We have a whole organization here. In some respect they’re trying to work with us, but they’re working with us on their terms. This is a brand new approach that I’m not familiar with.”

in an older city like Philadelphia that still practices machine politics. But the political leadership here is watching with dismay and growing resentment. “They have paid college kids coming to our community and trying to get us to volunteer — for them, not with them,” said Greg Paulmier, 49, the neighborhood ward leader for the last 14 years. “We have a whole organization here. In some respect they’re trying to work with us, but they’re working with us on their terms. This is a brand new approach that I’m not familiar with.”

For the Obama campaign, the territory is under the control of a 19-year-old college student, Max Stahl. A Massachusetts native taking a year off from school, Stahl is committed to the Obama view of field work. The ring tone on his cellphone is the John Lennon song “Power to the People.” He sees his job as recruiting volunteers to do the hard and unglamorous work of getting Obama elected: knocking on doors in hopes of coaxing voters to the polls.Standing outside the campaign office in Germantown, Stahl complained that Paulmier wasn’t working hard enough for the candidate. “Greg’s not making calls quick enough to committee people,” Stahl told Sawyer on a recent afternoon. “He said he made ‘a few.’ I’ll take that to mean zero.”

“If this were a yard sign primary, Hillary Clinton would have won South Carolina and Iowa big-time,” said Stahl, dressed in a T-shirt, jeans and sweatshirt. “We’re focused on different things. We’re focused on talking to people and getting them out to vote.” Speaking of the young Obama workers, Sawyer said: “To them, hats, yard signs and T-shirts are out of the Stone Age. They’re about the Internet, cellphones and BlackBerrys. It’s all digital, conceptual and theoretical. But people here want stuff. . . . They want T-shirts and hats and buttons.” He points to an Obama button on his shirt. “They want these buttons!”

And they want money.

And they want money.

For decades, candidates have passed money to city ward bosses, who in turn give it out to the committee people and party loyalists under their jurisdiction. Called street money, it is used for any number of purposes. In its most noble form, it reimburses people for gas, coffee or other legitimate expenses rung up on election day. But even the system’s proponents acknowledge the cash payouts are occasionally abused.

The Obama campaign has told the local ward bosses they’re not paying out street money this year, a position that has stirred criticism. At a time when Obama is pulling in tens of millions of dollars in campaign money every month, the city’s ward bosses are mystified. They know he can afford it. “Maybe in other parts of the country you can come in and you have people who are not really into politics and they’re excited about working for a candidate, but Philadelphia is not one of those places,” said Betty Townes, a committeewoman from Germantown.

“This is old-time politics here.” MORE