BY CHRISTOPHER CALDWELL FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES In March, the Massachusetts House of Representatives rejected a measure that looked unstoppable when it was proposed by Gov. Deval Patrick last September: the authorization of “destination casinos” across the commonwealth. The plan was for Massachusetts to sell three 10-year licenses for at least $200 million apiece and then tax the casinos’ takings at 27 percent, raking in $400 million a year. That, went the reckoning, would cover a $1.3 billion budget shortfall. Patrick was backed by The Boston Globe, big casino corporations and some trade unions. His opponent, the House speaker, Salvatore DiMasi, warned of “human devastation” and suggested that Massachusetts could aim higher. “We are the Athens of America,” DiMasi said at a St. Patrick’s Day breakfast. “Do we really want this? Do we need this casino culture?”

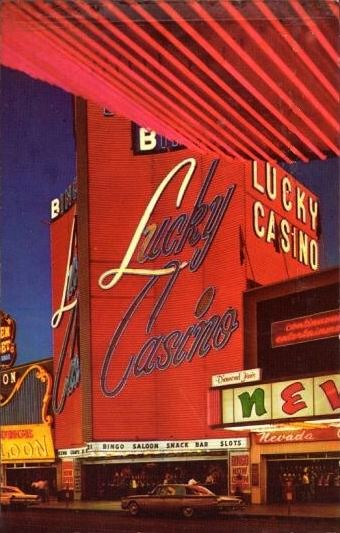

There are now more than 500 casinos in the U.S., most of them set up over the last two decades. They account for more than half of the almost $100 billion that Americans wager every year. Cash-strapped states and cities can tap this money through taxes and fees. Kansas recently legalized gambling to better finance education (with the money of people across the state line in Kansas City, Mo.). Detroit uses its three casinos for urban renewal, Indian betting resorts in Connecticut have replaced jobs lost to military downsizing and Western tribes use gambling for development aid. Like tax cuts in the mind of a supply-sider, casinos are the answer no matter what the question. They create money out of thin air.Anyone who believes this is likely to see the battle in Massachusetts as a contest between sophisticated libertarians (Patrick) and tut-tutting prudes (DiMasi). But that is a mistake. Liberty isn’t the issue. Patrick’s conviction that you can balance the budget with blackjack and slot machines depends as much on the moral disapproval of gambling as DiMasi’s skepticism does. Consider: If a state wants to get involved in a business, why does it have to pick a vice like gambling? Why can’t it run, say, a chain of ice-cream parlors? The answer is that collecting huge fees or taxes requires huge profits. Huge profits require monopolies (or oligopolies). Yet no mainstream politician today defends monopoly on economic grounds. Someone who proposed shuttering every Ben & Jerry’s in Massachusetts in order to make way for a state ice-cream scheme would be dismissed as unhinged. The only grounds for setting up a gambling monopoly are moral ones. Patrick’s vision of billions in betting revenues relies on the folk wisdom that gambling is too dangerous and corrupting to be left to the free market.

more than half of the almost $100 billion that Americans wager every year. Cash-strapped states and cities can tap this money through taxes and fees. Kansas recently legalized gambling to better finance education (with the money of people across the state line in Kansas City, Mo.). Detroit uses its three casinos for urban renewal, Indian betting resorts in Connecticut have replaced jobs lost to military downsizing and Western tribes use gambling for development aid. Like tax cuts in the mind of a supply-sider, casinos are the answer no matter what the question. They create money out of thin air.Anyone who believes this is likely to see the battle in Massachusetts as a contest between sophisticated libertarians (Patrick) and tut-tutting prudes (DiMasi). But that is a mistake. Liberty isn’t the issue. Patrick’s conviction that you can balance the budget with blackjack and slot machines depends as much on the moral disapproval of gambling as DiMasi’s skepticism does. Consider: If a state wants to get involved in a business, why does it have to pick a vice like gambling? Why can’t it run, say, a chain of ice-cream parlors? The answer is that collecting huge fees or taxes requires huge profits. Huge profits require monopolies (or oligopolies). Yet no mainstream politician today defends monopoly on economic grounds. Someone who proposed shuttering every Ben & Jerry’s in Massachusetts in order to make way for a state ice-cream scheme would be dismissed as unhinged. The only grounds for setting up a gambling monopoly are moral ones. Patrick’s vision of billions in betting revenues relies on the folk wisdom that gambling is too dangerous and corrupting to be left to the free market.

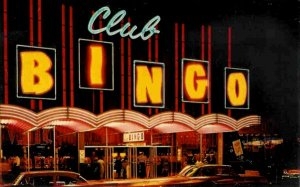

Measures to spread gambling generally involve dressing up regulation as deregulation. A referendum on the ballot in Maryland this fall, championed by Martin O’Malley, the Democratic governor, will ask voters to amend the state Constitution to permit 15,000 slot machines. But, in fact, thanks to a loophole in the “charitable gambling” laws meant to facilitate raffles and bingo, there already are thousands of gambling machines in barrooms across Maryland. Oddly, the state senate is moving ahead on a bill to ban these machines — even as the state prepares the referendum to “legalize” gambling.

Measures to spread gambling generally involve dressing up regulation as deregulation. A referendum on the ballot in Maryland this fall, championed by Martin O’Malley, the Democratic governor, will ask voters to amend the state Constitution to permit 15,000 slot machines. But, in fact, thanks to a loophole in the “charitable gambling” laws meant to facilitate raffles and bingo, there already are thousands of gambling machines in barrooms across Maryland. Oddly, the state senate is moving ahead on a bill to ban these machines — even as the state prepares the referendum to “legalize” gambling.

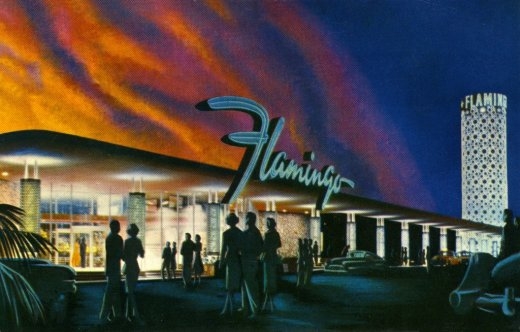

Casinos are marketed to voters the same way they are marketed to patrons — by accentuating moments of exhilaration and playing down the way the business is designed to take in more money than it pays out. The image of the gambler that casinos want to convey is of someone wild, free, savvy, like a rogue in a cologne ad or a John Ford movie. He knows when to hold ’em, knows when to fold ’em. This image is meant not only to flatter the gambler but also to legitimize the casino. Mister Free Spirit wouldn’t play a rigged game.

There is a catch, though. The most important segment of gamblers is not free. And those gamblers are important because they are not free. Compulsive and problem gamblers make up only 2.4 percent of gamblers, according to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission, but they account for a third of receipts, or more. A 1995 Minnesota study found that 1 percent of patrons made half the wagers. Where you have saturation gambling, as in Las Vegas, about two-thirds of residents at least try it — and 2.4 percent of that two-thirds is a ton of problem gamblers. It translates into rises in suicide, embezzlement and bankruptcy that have real social costs.

Nonpathological gambling has its costs, too. Introduce casinos in Massachusetts, and you will indeed recapture some of the hundreds of millions of dollars that Bay Staters drop in the resorts of Connecticut. But you will also capture a lot of money that people would have spent in local restaurants and movie theaters. The infrastructure required for gambling — from road building to hiring new police — is costly as well. Once you make those adjustments, the economic upside of gambling evaporates. The economist Earl Grinols estimates the ratio of gambling costs to gambling benefits at higher than three to one. Voters sense this. The rule of thumb, according to Grinols, is that pro-gambling interests lose referendum battles whenever they do not outspend their opponents by at least 75 to 1.

some of the hundreds of millions of dollars that Bay Staters drop in the resorts of Connecticut. But you will also capture a lot of money that people would have spent in local restaurants and movie theaters. The infrastructure required for gambling — from road building to hiring new police — is costly as well. Once you make those adjustments, the economic upside of gambling evaporates. The economist Earl Grinols estimates the ratio of gambling costs to gambling benefits at higher than three to one. Voters sense this. The rule of thumb, according to Grinols, is that pro-gambling interests lose referendum battles whenever they do not outspend their opponents by at least 75 to 1.

Gambling appears a less glamorous habit when the country is digging its way out of mortgage and credit-card debt. In mid-March, the Colorado Division of Gaming announced that revenues at local gambling resorts were down 10 percent. The next day, Moody’s Investors Service reported that casino revenues in January dropped 17 percent in Illinois, 10 percent in Atlantic City and 8 percent in Indiana. Maybe Massachusetts knows something these places don’t. But you don’t have to live in the Athens of America to see that our economy is one in which those who know when to fold ’em are foldin’ ’em. [via NEW YORK TIMES]