FRESH AIR![]()

BY ED WARD FRESH AIR MUSIC CRITIC In the past 20 years, Great Britain has produced a huge quantity of popular music  that’s gotten very little attention in the U.S. So much, in fact, that it’s practically impossible for American fans to keep up with it. In an attempt at a crash-course, Rhino released a four-disc collection titled The Brit Box late last year.

that’s gotten very little attention in the U.S. So much, in fact, that it’s practically impossible for American fans to keep up with it. In an attempt at a crash-course, Rhino released a four-disc collection titled The Brit Box late last year.

The British music scene is very different from the American one. Britain is, and always has been, the home of pop — music which revolves around the three-minute single, produced by fresh new faces promoting fashions in clothing and lifestyle, who may or may not have staying power. It hardly matters: There are always more where they came from.

Once punk became established on the U.K. charts by the early ’80s, the question became “What next?” and a young man named Steven Patrick Morrissey decided to answer it directly. Fortunately, in Manchester, where he lived, there were plenty of young musicians eager to upset the city’s traditional rival, Liverpool. One was a guitarist named Johnny Marr, who was a genius. Their band, The Smiths, released a single, “How Soon Is Now,” which sounded like nothing which had come before, and a new era in British pop was born.

By the end of the ’80s, pop was influenced by dance music, and the music was almost inevitably released on small labels, at least at first. Scotland was another fertile area for the new pop sounds. The Jesus and Mary Chain, fronted by brothers William and Jim Reid, introduced a sound classic enough to give it a string of hits. The British rock press — weekly papers like New Music Express and Melody Maker — stirred up controversy, pitting “rockist” bands which relied on traditional guitars against the ones who used keyboards and synthesizers, and often had their singles remixed by dance-music producers. But the reality was that the fans were listening for songs that stuck in your head. The bands only needed one to achieve fame. The La’s, from Liverpool, were a perfect example. The song “There She Goes,” from 1988, was a pop masterpiece, but the band is still working on its second album. Others never even got that far: Creating an album’s worth of material was hard, and although most did it, it didn’t mean the fans had to buy it.

THE LA’S: There She Goes

The American music business of the time was more conservative, looking not only for singles that were well-defined in terms of melody, lyrics, and structure, but also for bands that could tour and play their stuff live. Not all the kids with a well-produced single who were catapulted to fame on a small island had the right stuff to sustain a career. Still, some of them did. MORE

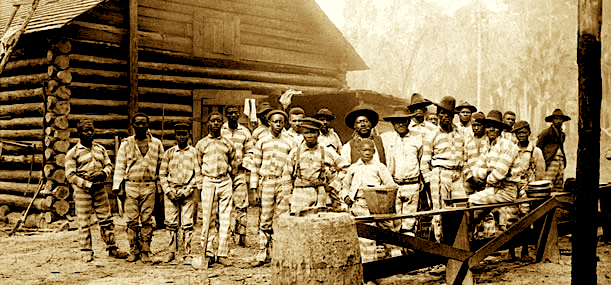

In Slavery by Another Name, Douglas Blackmon of the Wall Street Journal argues that slavery did not end in the United States with the Emancipation Proclamation in 1862. He writes that it continued for another 80 years, in what he calls an “Age of Neoslavery.” “The slavery that survived long past emancipation was an offense permitted by the nation,” Blackmon writes, “perpetrated across an enormous region over many years and involving thousands of extraordinary characters.”

EXCERPT: Slavery By Another Name By Douglas Blackmon

On March 30, 1908, Green Cottenham was arrested by the sheriff of Shelby County, Alabama, and charged with “vagrancy.” Cottenham had committed no true crime. Vagrancy, the offense of a person not being able to prove at a given moment that he or she is employed, was a new and flimsy concoction dredged up from legal obscurity at the end of the nineteenth century by the state legislatures of Alabama and other southern states. It was capriciously enforced by local sheriffs and constables, adjudicated by mayors and notaries public, recorded haphazardly or not at all in court records, and, most tellingly in a time of massive unemployment among all southern men, was reserved almost exclusively for black men. Cottenham’s offense was blackness.

After three days behind bars, twenty-two-year-old Cottenham was found guilty in a swift appearance before the county judge and immediately sentenced to a thirty-day term of hard labor. Unable to pay the array of fees assessed on every prisoner — fees to the sheriff, the deputy, the court clerk, the witnesses— Cottenham’s sentence was extended to nearly a year of hard labor.

The next day, Cottenham, the youngest of nine children born to former slaves in an

adjoining county, was sold. Under a standing arrangement between the county and a vast subsidiary of the industrial titan of the North — U.S. Steel Corporation — the sheriff turned the young man over to the company for the duration of his sentence. In return, the subsidiary, Tennessee Coal, Iron & Railroad Company, gave the county $12 a month to pay off Cottenham’s fine and fees. What the company’s managers did with Cottenham, and thousands of other black men they purchased from sheriffs across Alabama, was entirely up to them.

A few hours later, the company plunged Cottenham into the darkness of a mine called Slope No. 12 — one shaft in a vast subterranean labyrinth on the edge of Birmingham known as the Pratt Mines. There, he was chained inside a long wooden barrack at night and required to spend nearly every waking hour digging and loading coal. His required daily “task” was to remove eight tons of coal from the mine. Cottenham was subject to the whip for failure to dig the requisite amount, at risk of physical torture for disobedience, and vulnerable to the sexual predations of other miners — many of whom already had passed years or decades in their own chthonian confinement. The lightless catacombs of black rock, packed with hundreds of desperate men slick with sweat and coated in pulverized coal, must have exceeded any vision of hell a boy born in the countryside of Alabama — even a child of slaves — could have ever imagined. MORE