SLATE: Why, exactly, is prostitution illegal? The case for making it against the law to buy sex begins with the premise that it’s base and exploitative and demeaning to sex workers. Legalizing prostitution expands it, the argument goes, and also helps pimps, fails to protect women, and leads to more back-alley violence, not less. This fight over legalization has been waged in the last few years over international human-trafficking laws and proposals to make prostitution legal in countries like Bulgaria, a movement that the U.S. government helped defeat. In 2004, the federal government expressed its position: “The United States government takes a firm stance against proposals to legalize prostitution because prostitution directly contributes to the modern-day slave trade and is inherently demeaning.” The government also claims that legalizing or tolerating prostitution creates “greater demand for human trafficking victims.” And yet, prostitution is legal in parts of Nevada, a companion to other cherished vices.

SLATE: Why, exactly, is prostitution illegal? The case for making it against the law to buy sex begins with the premise that it’s base and exploitative and demeaning to sex workers. Legalizing prostitution expands it, the argument goes, and also helps pimps, fails to protect women, and leads to more back-alley violence, not less. This fight over legalization has been waged in the last few years over international human-trafficking laws and proposals to make prostitution legal in countries like Bulgaria, a movement that the U.S. government helped defeat. In 2004, the federal government expressed its position: “The United States government takes a firm stance against proposals to legalize prostitution because prostitution directly contributes to the modern-day slave trade and is inherently demeaning.” The government also claims that legalizing or tolerating prostitution creates “greater demand for human trafficking victims.” And yet, prostitution is legal in parts of Nevada, a companion to other cherished vices.

You don’t have to be a moralist or a prude to buy the argument for banning prostitution. But if you’re so inclined, it’s an easy one to take apart. Martha Nussbaum, a law and philosophy professor at the University of Chicago, argues that lots of work involves the sale of bodily services and that lots of the work that poor women do involves bad working conditions. For her, it’s all about context—there’s a big difference between a street worker controlled by a pimp and a high-end call girl who picks her own clients, and the real question is how to increase poor women’s access to decent and safe work in general. Legalizing prostitution “is likely to make things a little better for women who have too few options to begin with,” Nussbaum writes.

context—there’s a big difference between a street worker controlled by a pimp and a high-end call girl who picks her own clients, and the real question is how to increase poor women’s access to decent and safe work in general. Legalizing prostitution “is likely to make things a little better for women who have too few options to begin with,” Nussbaum writes.

The extremely pricey outfit Spitzer apparently used looks like an example of the high-end trade Nussbaum would distinguish from low-rent street work. The further defense of such escort services is that prostitution is inevitable and that conditions will be better for everyone all around if it’s regulated (more condoms, fewer beatings). This parallels the argument against Prohibition or in favor of drug legalization: Illegality puts the bad guys and their guns in control. Women who fear prosecution can’t go to the police for help. Better to give women more recourse to head off abuse and even inspect brothels for health-code violations. MORE

PREVIOUSLY: How Eliot Spitzer Became The Most Powerful Man On Wall Street

BOSTON NOW: Alan Dershowitz has been the only famous name to come out and defend Eliot Spitzer. If I understand where Alan Dershowitz is coming from, he believes that laws against prostitution are unjust. Dershowitz wishes to remove unethical prohibitions and mandates from the law books. I completely agree that laws against prostitution are unjust and should be removed. I also would stand with Alan Dershowitz in defending average people who are caught violating such laws. However, in the case of Gov. Spitzer, the better way to attack unethical laws is to speak out against Client #9. Here are some reasons: People who run for political office sometimes are motivated to do so to erase unjust prohibitions and mandates (these people are called Libertarians). Gov. Spitzer, on the other hand, is a famous champion of increasing and enforcing unjust unethical government mandates and prohibitions. Gov. Eliot Spitzer is all too happy to use government to hurt other people for doing the same thing he loves to do. Unlike a private citizen, Gov. Eliot Spitzer used government resources to order prostitutes, and he also used his state police security to protect his personal space as he broke the law. MORE

BOSTON NOW: Alan Dershowitz has been the only famous name to come out and defend Eliot Spitzer. If I understand where Alan Dershowitz is coming from, he believes that laws against prostitution are unjust. Dershowitz wishes to remove unethical prohibitions and mandates from the law books. I completely agree that laws against prostitution are unjust and should be removed. I also would stand with Alan Dershowitz in defending average people who are caught violating such laws. However, in the case of Gov. Spitzer, the better way to attack unethical laws is to speak out against Client #9. Here are some reasons: People who run for political office sometimes are motivated to do so to erase unjust prohibitions and mandates (these people are called Libertarians). Gov. Spitzer, on the other hand, is a famous champion of increasing and enforcing unjust unethical government mandates and prohibitions. Gov. Eliot Spitzer is all too happy to use government to hurt other people for doing the same thing he loves to do. Unlike a private citizen, Gov. Eliot Spitzer used government resources to order prostitutes, and he also used his state police security to protect his personal space as he broke the law. MORE

RELATED: But in the end, it appears that Spitzer may have been done in by the same behavior he built a career out of prosecuting. In fact, it seems he was tripped up by some of the very financial accounting methods he used so successfully against multibillion-dollar Wall Street firms. For one thing, the governor initially drew the attention of federal investigators because of cash payments to an account operated by a call-girl ring, according to a law enforcement official who spoke on condition of because of the sensitivity of the case.Banks are required to file Suspicious Activity Reports to the government whenever they observe something they fear may be a crime. In court papers, Client 9 — identified by another law enforcement official as Spitzer — hurried to get more than $4,000 in cash to pay a call girl at a Washington hotel.That kind of activity, repeated over time, is just the kind of thing that would set off alarm bells with a bank’s compliance officer, who is trained to be on the lookout for what is called structuring or “smurfing” — a pattern of transactions aimed at hiding the nature or purpose of certain money. Spitzer of all people should have known that, said Miami-based lawyer Gregory Baldwin, credited with coining the term “smurfing” in the 1980s as a federal prosecutor. MORE

out of prosecuting. In fact, it seems he was tripped up by some of the very financial accounting methods he used so successfully against multibillion-dollar Wall Street firms. For one thing, the governor initially drew the attention of federal investigators because of cash payments to an account operated by a call-girl ring, according to a law enforcement official who spoke on condition of because of the sensitivity of the case.Banks are required to file Suspicious Activity Reports to the government whenever they observe something they fear may be a crime. In court papers, Client 9 — identified by another law enforcement official as Spitzer — hurried to get more than $4,000 in cash to pay a call girl at a Washington hotel.That kind of activity, repeated over time, is just the kind of thing that would set off alarm bells with a bank’s compliance officer, who is trained to be on the lookout for what is called structuring or “smurfing” — a pattern of transactions aimed at hiding the nature or purpose of certain money. Spitzer of all people should have known that, said Miami-based lawyer Gregory Baldwin, credited with coining the term “smurfing” in the 1980s as a federal prosecutor. MORE

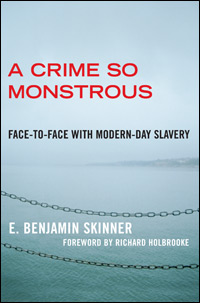

RELATED: With $50 and a plane ticket to Haiti, one can buy a slave. This was just one of the difficult lessons writer Benjamin Skinner learned while researching his book, A Crime So Monstrous: Face-to-Face with Modern-Day Slavery. Skinner met with slaves and traffickers in 12 different countries, filling in the substance around a startling fact: there are more slaves on the planet today than at any time in human history. Skinner speaks with Anthony Brooks about his experience researching slavery. Though now illegal throughout the world, slavery is more or less the same as it was hundreds of years ago, Skinner explains. Slaves are still “those that are forced to work under threat of violence for no pay beyond sustenance.” Something disturbing has changed however — the price of a human. After adjusting for inflation, Skinner found that, “In 1850, a slave would cost roughly $30,000 to $40,000 — in other words it was like investing in a Mercedes. Today you can go to Haiti and buy a 9-year-old girl to use as a sexual and domestic slave for $50. The devaluation of human life is incredibly pronounced.” MORE

RELATED: With $50 and a plane ticket to Haiti, one can buy a slave. This was just one of the difficult lessons writer Benjamin Skinner learned while researching his book, A Crime So Monstrous: Face-to-Face with Modern-Day Slavery. Skinner met with slaves and traffickers in 12 different countries, filling in the substance around a startling fact: there are more slaves on the planet today than at any time in human history. Skinner speaks with Anthony Brooks about his experience researching slavery. Though now illegal throughout the world, slavery is more or less the same as it was hundreds of years ago, Skinner explains. Slaves are still “those that are forced to work under threat of violence for no pay beyond sustenance.” Something disturbing has changed however — the price of a human. After adjusting for inflation, Skinner found that, “In 1850, a slave would cost roughly $30,000 to $40,000 — in other words it was like investing in a Mercedes. Today you can go to Haiti and buy a 9-year-old girl to use as a sexual and domestic slave for $50. The devaluation of human life is incredibly pronounced.” MORE