BY JEFF DEENEY Newly anointed police chief Ramsey released his crime fighting strategy yesterday, a very readable and accessible 22 page document that provides a first look into the mind of the man who will be leading the charge against violent crime as the Nutter administration ramps up. The Nutter administration continues to look promising to me; he’s moved fast to get promised policy documents into the public’s hands and there is a sense I think most of us share that some shit is finally starting to get done around here. Last week some major, desperately needed changes were announced regarding the Department of Human Services and the provision of child welfare protections. This week, we have a new direction for law enforcement. High fives, DJ Mike, for getting this party started right, and, most importantly, on time.

BY JEFF DEENEY Newly anointed police chief Ramsey released his crime fighting strategy yesterday, a very readable and accessible 22 page document that provides a first look into the mind of the man who will be leading the charge against violent crime as the Nutter administration ramps up. The Nutter administration continues to look promising to me; he’s moved fast to get promised policy documents into the public’s hands and there is a sense I think most of us share that some shit is finally starting to get done around here. Last week some major, desperately needed changes were announced regarding the Department of Human Services and the provision of child welfare protections. This week, we have a new direction for law enforcement. High fives, DJ Mike, for getting this party started right, and, most importantly, on time.

The plan, as you have probably heard by this point, will focus the city’s law enforcement resources on the nine police districts with the highest rates of violent crime without allowing a crime increase in the safer districts. There are some bold performance goals, including a 25% drop in homicides, a 20% decrease in other shootings, and a 20% decrease in other violent crimes. How, exactly, does Chief Ramsey intend to get that done? It’s a big task that’s going to require some major restructuring and resource re-allocation in the department, and the question is whether or not Ramsey will be able to effectively implement this institutional reorganization without a substantial increase in budget.

There are some bold performance goals, including a 25% drop in homicides, a 20% decrease in other shootings, and a 20% decrease in other violent crimes. How, exactly, does Chief Ramsey intend to get that done? It’s a big task that’s going to require some major restructuring and resource re-allocation in the department, and the question is whether or not Ramsey will be able to effectively implement this institutional reorganization without a substantial increase in budget.

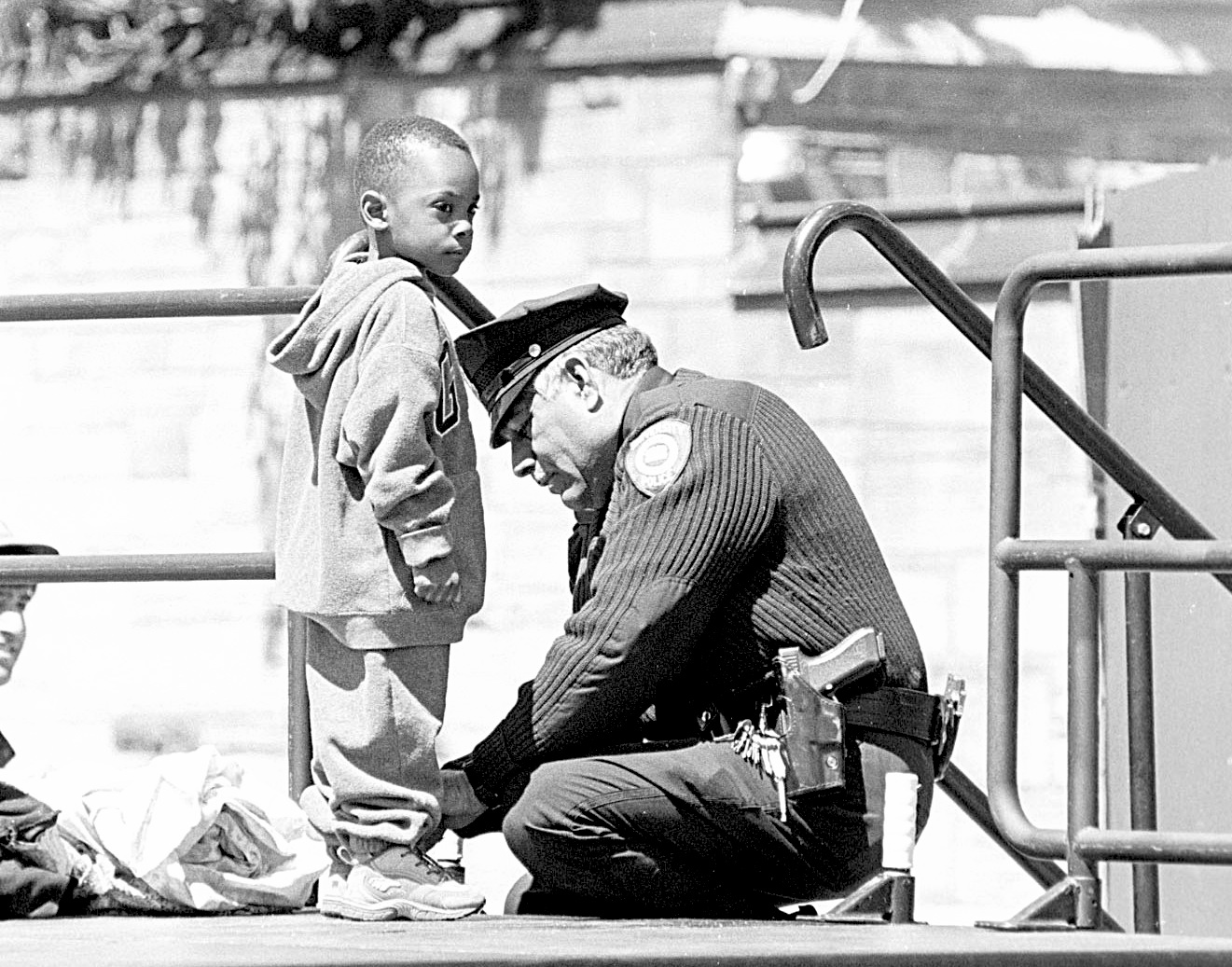

Ramsey repeatedly returns throughout the document to the stated needs of the residents in the nine districts. This is nice. One gets the sense in the early pages of the plan that Ramsey is going to at least attempt to be a bridge builder between law enforcement, neighbors, neighborhood grassroots organizations and social services providers.

The stated needs of nine districts shouldn’t surprise anybody:

“Residents want the police to stop the violence, eliminate illegal drug markets, get illegal guns off the street, increase police visibility, foot and bike patrols in the neighborhoods, improve communication between detectives and victims, participate as a full partner in intervention and prevention programs, address quality of life issues and crimes, focus on truancy and curfew violators, help intervene with young people who are threatening and frightening neighbors, and help improve school safety and passage to and from school. This is just a partial list of concerns, but they are common across the city.”

It’s important to note that the needs of the police force follow directly after the needs of the nine districts in Ramsey’s plan, and it gives you an indication of the sorry state that the Street administration left the police department in, and highlights the importance of balancing the needs of the people against the needs of city personnel.

“These (needs) include vehicles in working condition, modern technology and real-time information, more personnel, better training, improved deployment, and facilities that are habitable.”

Vehicles in working conditions. Habitable facilities. These should not be luxuries, but in Philadelphia, the land of ever-shrinking population and tax base, a city vehicle that starts when you turn the key is luxury. Uninhabitable facilities and failing equipment sends a message to officers. It says that the city isn’t really serious about fighting crime. These things keep morale persistently low. This is a good starting point for meaningful change.

Vehicles in working conditions. Habitable facilities. These should not be luxuries, but in Philadelphia, the land of ever-shrinking population and tax base, a city vehicle that starts when you turn the key is luxury. Uninhabitable facilities and failing equipment sends a message to officers. It says that the city isn’t really serious about fighting crime. These things keep morale persistently low. This is a good starting point for meaningful change.

The meat of this plain Jane plan (there is “nothing fancy” about it, according to Ramsey) centers around the simple idea of maintaining a sustained, elevated police presence in “Targeted Enforcement Zones” of high violent crime concentration, and staying on top of violent crime as it responds to increased police presence and starts to migrate elsewhere. Ramsey intends to get the man power he needs by restructuring the department, redeploying man power from special units and even administrative staff. New recruits will do mandatory tours in one of the nine districts, and existing officers will work overtime to provide adequate staffing during the crucial 3pm-3am time chunk when the majority of violent crimes occur.

It’s crucial to note the difference in tone set by Ramsey’s plan from those previously implemented, like Operation Safe Streets and its many sequels. Ramsey understands that his proposed elevated presence in the nine districts needs to be sustained, and it needs to be flexible, ready to move with the crime as it responds to his plan. Operations Safe Streets, by contrast, flooded known high drug and crime areas with an unsustainable level man power and was a relatively static measure that didn’t respond to crime trends.

The lesson of Safe Streets was that, of course, if you park four patrol cars one on each corner of Hancock and Somerset around the clock for weeks at a stretch, the open air drug markets that used to operate there will be disrupted. But what Safe Streets didn’t anticipate is that this disruption would be short lived, and that organized drug cartels would respond to law enforcement efforts, restructuring and redeploying their own resources into other areas. The end result was that drug distribution and its associated social problems spread out over a broader area, and when the costs of maintaining Safe Streets became too prohibitive and the program was phased out, the corners it targeted were reopened for business. The end result was that homicide rates weren’t impacted long term. I think both Ramsey and Nutter are pretty well versed in all of this and the plan reflects at least an attempt at the outset to learn from history.

drug cartels would respond to law enforcement efforts, restructuring and redeploying their own resources into other areas. The end result was that drug distribution and its associated social problems spread out over a broader area, and when the costs of maintaining Safe Streets became too prohibitive and the program was phased out, the corners it targeted were reopened for business. The end result was that homicide rates weren’t impacted long term. I think both Ramsey and Nutter are pretty well versed in all of this and the plan reflects at least an attempt at the outset to learn from history.

There are far more specific details in the plan about executing warrants, working with parole and probation officers, improving homicide clearance rates and strengthening bonds to community groups; in fact, there’s too many bullet points to deal with here. I will say that the only concern I was left with at the end of the document was that there weren’t any budget numbers laid out, so it’s difficult to ascertain whether Ramsey’s intended substantial increase of overtime and infrastructure improvements are monetarily feasible.

Lastly, there will be plenty of discussion, I’m sure about Ramsey’s trotting out the “Broken Windows” theory, which he claims, is “an effective tools for the police and communities to reclaim and maintain neighborhoods.” The bottom line is that nothing is conclusive about the long term impact of broken windows policing, which amounts to strictly enforcing quality of life infractions with the intention of creating a ripple effect of increased order that will resonate through the system, causing a decrease in crime, ala Giuliani-era New York. Just about every heavy weight social thinker has weighed in on Broken Windows at one point or another over the past 25 years, and for every Steven Levitt who says that Broken Windows is a correlate and not a causal factor for crime reduction you have a Malcolm Gladwell who thinks that order maintenance is an integral part of law enforcement that definitely reduces crime in the long term.

The problem in figuring out exactly what, if anything, Broken Windows does, is that crime is an enormously complicated proposition with myriad associated correlates and cultural particularities. Teasing out the impact of one correlate from another when crime drops suddenly and precipitously like it did in the 1990s in New York is difficult to say the least, and compelling cases can be made for a number of different hypotheses while irrefutable proof can be offered for none.

However, the one thing that nearly all Broken Windows theorists will agree on is that in the 1990s one major correlate involved in the falling crime rate in New York was an economic surge. Basically, if you’re going to police quality of life issues, running hookers and vagrants out of Times Square, it doesn’t hurt to have a long line of multinational corporations waiting to flood the same space with millions of dollars worth of investment. Unfortunately Philadelphia in 2008 is not the center of global finance the way New York was in the 1990s, and we’re entering into what some forecasters are predicting might be a long and deep recession. You can run the ladies off Kensington Avenue, you can board up abandos, and you can scrub off graffiti, sure. Then what?

However, the one thing that nearly all Broken Windows theorists will agree on is that in the 1990s one major correlate involved in the falling crime rate in New York was an economic surge. Basically, if you’re going to police quality of life issues, running hookers and vagrants out of Times Square, it doesn’t hurt to have a long line of multinational corporations waiting to flood the same space with millions of dollars worth of investment. Unfortunately Philadelphia in 2008 is not the center of global finance the way New York was in the 1990s, and we’re entering into what some forecasters are predicting might be a long and deep recession. You can run the ladies off Kensington Avenue, you can board up abandos, and you can scrub off graffiti, sure. Then what?

This isn’t to say that Ramsey shouldn’t follow through with Broken Windows policing. Why? Because if you remember a couple paragraphs back when the residents of the nine districts got to speak their piece, they asked Ramsey to do it. But I think if there will be any real, lasting impact from Ramsey’s plan, it’s going to come from the “nothing special” increase of a well resourced and flexible police presence in the highest crime areas of the city.

The next step? Implementation. It looks great on paper, now let’s see if Ramsey gets it done. In a couple months we’ll check back on the PPD and see how effectively the plan is being rolled out.

More about Broken Windows:

The Atlantic Monthly article that started it all

Shattering “Broken Windows”: rebuttal to the Atlantic article

Malcolm Gladwell rebutting Freakonomics author Steven Levitt on Broken Windows

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jeff Deeney is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in PW, City Paper and the Inquirer. He focuses on issues of urban poverty and drug culture.