BY JEFF DEENEY Doron Taussig’s City Paper article “Mama Drama” details the backlash from one grassroots women’s coalition against the escalation of foster care placements by the Philadelphia Department of Human Services. The escalation comes in the wake of scathing news probes into an alarming number of child deaths taking place under DHA’s watch. It’s a touchy subject that draws strong reactions from all sides: DHS feels like they have stepped up to the plate, doing what was absolutely necessary to stamp out a crisis. Conversely, any mother, no matter how incapable of adequately caring for a child she may be, is going to go insane with anger at having her child taken away. Lost in the middle of this push and pull are the gray area cases, where both sides can muster compelling arguments for the right to keep or remove a kid.

BY JEFF DEENEY Doron Taussig’s City Paper article “Mama Drama” details the backlash from one grassroots women’s coalition against the escalation of foster care placements by the Philadelphia Department of Human Services. The escalation comes in the wake of scathing news probes into an alarming number of child deaths taking place under DHA’s watch. It’s a touchy subject that draws strong reactions from all sides: DHS feels like they have stepped up to the plate, doing what was absolutely necessary to stamp out a crisis. Conversely, any mother, no matter how incapable of adequately caring for a child she may be, is going to go insane with anger at having her child taken away. Lost in the middle of this push and pull are the gray area cases, where both sides can muster compelling arguments for the right to keep or remove a kid.

The choice to remove a child from the home is one of the most serious decisions the Commonwealth can make, ranking right up there with incarceration. A criminal not convicted is a danger to the community, but an innocent man wrongly convicted can also unjustly languish in prison. A child wrongly put into foster care suffers the trauma of being torn from its mother, but a child left in the hands of a truly unsuitable parent can suffer worse traumas, and perhaps die. It’s tough stuff, and there are no easy answers. The question here is whether or not DHS caseworkers are lending to their decisions the seriousness necessary to maintain a scrupulous child welfare system, one that adequately protects. Or are they arbitrarily pulling children from parents and abusing their power?

suffers the trauma of being torn from its mother, but a child left in the hands of a truly unsuitable parent can suffer worse traumas, and perhaps die. It’s tough stuff, and there are no easy answers. The question here is whether or not DHS caseworkers are lending to their decisions the seriousness necessary to maintain a scrupulous child welfare system, one that adequately protects. Or are they arbitrarily pulling children from parents and abusing their power?

The spike in foster care placements directly following the bad press DHS received last year struck me as quite possibly arbitrary, and the outcomes of these placements have not surprisingly sown some anguish. The fact is that prior to the Inquirer’s expose, the problem with DHS wasn’t their unwillingness to place children in foster care, but rather their inability to provide the necessary level of supervision and assistance to keep struggling or potentially unsuitable mothers from harming their children. It was inattention to clear warning signs, seriously deteriorating physical conditions and a general absence from homes in crisis that resulted in dead kids on DHS’s caseload. To react to this lack of institutional competence by increasing foster placements doesn’t necessarily address the root problem.

Though I’ve never worked in child welfare, my path as a social worker has crossed with DHS’s a number of times. I’ve heard DHS social workers tell clients in a don’t-test-me tone of voice, “You know we’re placing kids right now.” What initially started as a last-ditch effort to appear in the eyes of the public as an agency in action turned into an ax for caseworkers to hold over their clients’ necks to keep them in check. Not surprisingly, moms with DHS involvement in their homes have come to resent the agency more than they already did.

The real root of the problem is twofold, and unfortunately neither element comprising it is likely to change soon, though neither requires increased foster placements to fix. The first part of the problem, illustrated above, is that DHS is one of those old school social service agencies that haven’t figured out yet that trying to force clients into compliance through threats and coercion doesn’t get long-term results. The better social service agencies have bent over backwards in recent years to level the previously skewed power balances between clients and service providers. They understand that threatening and coercing a client into complying produces a fundamentally adversarial relationship. Clients with the old school agencies make their primary objective to hide as much as possible from their caseworkers in order to prevent the caseworkers from taking something valuable from them.

Most moms living in extreme poverty (the kind most likely to wind up with a kid in foster care) know exactly what a DHS home inspection entails. They know from word of mouth that their home has to be clean and there has to be food in the fridge if DHS comes around. They know that the presence of illegal activity in the building will be counted as a strike against them, and DHS will try to compel them to move to a different neighborhood, which they probably can’t afford. So, before the caseworker comes by, they’ll have friends over to help them clean up any housekeeping situations that may have gotten out of their control. They’ll borrow a friend’s Access card if they have to so the fridge doesn’t look as empty as it did yesterday. If there’s drug activity on the block, they might ask the dealers to temporarily close shop should they see someone who looks like a social worker.

The real problems underlying why Mom can’t keep her house together, keep food in the cupboard and provide safe housing for her children is neither discussed nor resolved. Mom doesn’t want to share her problems with her social worker because she’s afraid the information will be used to make a case against her. And the last thing any mother wants is to lose her kids to the system.

The second part of the problem, which partially explains why DHS still relies so much on compliance and coercion, is that caseworkers with the agency are literally buried under insurmountable caseloads. The department, like most city departments, is critically under funded and under staffed. Social services for a city agency produces volumes of paper work that would make most people’s heads explode. The time for quality interaction with clients, where a relationship could be built and lasting impact on children’s lives made, simply doesn’t exist. So DHS uses the skewed power dynamic based on the ability to place children in foster care to keep clients in line, because keeping clients in line is all they have time to accomplish.

This partially explains the more miserable aspects of life as a DHS mom described in the CP article (“the unreturned phone calls, the dismissive treatment . . .”). A lot of DHS social workers don’t answer the phone because it never stops ringing. They screen their calls for priority contacts, though a good social worker will try to return all calls as fast as possible. But this lag time might be too long for an agitated mom. DHS social workers are sometimes verbally (and even physically) assaulted by hostile clients and it can become difficult to muster a sweet façade after enduring abuse day after day. This harried dynamic further aggravates what started as an adversarial relationship. But before casting judgment, imagine yourself in their shoes. It’s an emotionally taxing population to serve, and service provision is frustrated by myriad macro-level, institutional problems.

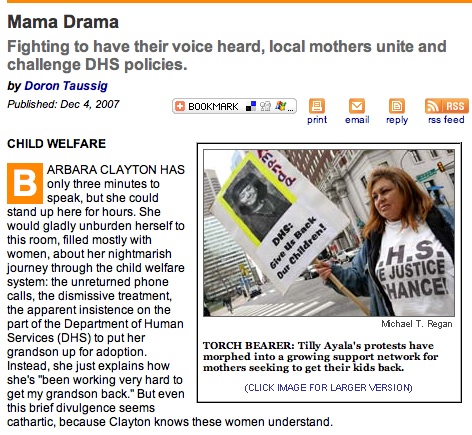

Finally, we have the case of Tilly Ayala, the mom whose kid was purportedly taken from her because, “her (now former) husband scared passers-by on a beach by saying that he had a baby for sale.” Now, it doesn’t take a brain surgeon to know that playing beer-vendor-at-the-baseball-game with your newborn child held aloft like it’s a lukewarm cup of Coors and offering it for sale to complete strangers is an exercise of bad judgment. It’s a joke made in stunningly poor taste. But you know what? It’s not grounds for a foster care placement.

The article intimates that the foster care placement process has many steps, starting with the recommending social worker and ending up in front of a family court judge. The article also hints at the HIPPA client confidentiality protections that keep DHS from arguing their decision in any case publicly. And something tells me that if you were to get a look at Tilly’s case file, you’d find a lot more in there than a predilection for bad jokes. In fact, you might find out that there’s a lot more gray in each of the cases, presented as black and white incidents of power abuse by the advocates at Every Mother is a Working Mother Network. If only you knew all the details.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jeff Deeney is a freelance writer who has contributed to the City Paper, PW and the Inquirer. He focuses on issues of urban poverty and drug culture.