BEFORE THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU’RE DEAD (2007, directed by Sidney Lumet, 117 minutes, U.S.)

BEFORE THE DEVIL KNOWS YOU’RE DEAD (2007, directed by Sidney Lumet, 117 minutes, U.S.)

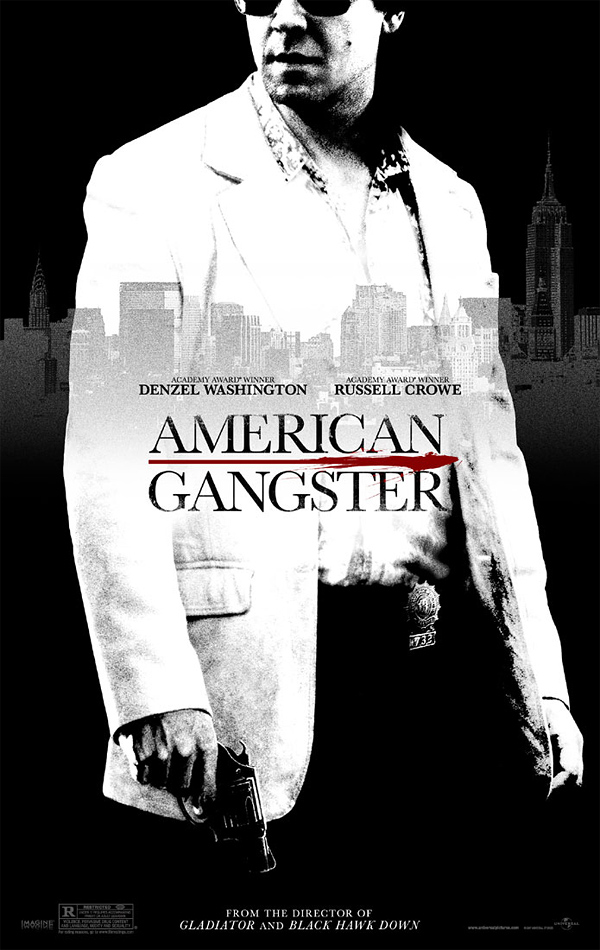

AMERICAN GANGSTER (2007, directed by Ridley Scott, 157 minutes, U.S.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

Talk about a Dream Factory. The modern Hollywood press machine now holds the power to make the backstory of a new theatrical release the front story, in a way that practically lets a film review itself. I’ve read, heard and viewed so many stories about how the 83-year-old master director Sidney Lumet was in top form with his latest crime drama, Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead, that it began to carry an air of unassailable truth. It’s a believable story and one that you would wish to be true. However, instead of a career high point, this film is a quintessential Lumet film, one that tends to show Lumet’s weaknesses as fully as his strengths.

The natural impulse to give respect to elder statesmen leads a writer to remind readers that Lumet has directed such well-respected classics as Twelve Angry Men and Serpico, all the while conveniently forgetting films a plethora of misfires like A Stranger Among Us, where policewoman Melanie Griffith hides out amongst the Brooklyn Hasidim. Truth is, Lumet’s filmography is littered with overlong police procedurals and pedestrian courtroom dramas as well as the occasional bull’s-eye (who could dislike Dog Day Afternoon?). Before the Devil does show off Lumet’s consistent strength with actors while continuing his record of letting so-so scripts collapse beneath his stodgy presentation.

Written by first-time screenwriter Kelly Masterson, it’s the story of Andy and Hank Hanson, two brothers who plan a low-key heist of their parents’ suburban jewelry store. We see the robbery go terribly wrong at the beginning of a film and then, ala Reservoir Dogs, we flash forwards and backwards in time to witness their fateful mistakes and the consequences.

It no surprise that Philip Seymour Hoffman is so good, coming off his improbable Oscar-wining performance in Capote, Hoffman plays the soured and scheming older brother Andy. In his banker’s suit he’ll remind you of Rush Limbaugh, giving a condescending laugh whenever his brother questions the ethics of robbing their parents. As the younger Hank, Hawke comes on like a sweaty used car salesman, trying to keep a game face while his heart is breaking daily. Both brothers are desperate for money; Hank is humiliated by not being able to make his child support payments and Andy needs the score to pay back embezzled cash before it is discovered and to keep his bored wife (the frequently nude Marisa Tomei) from getting too distracted.

We all know where this whole botched affair is heading by design but that doesn’t stop Lumet from slowly walking us through the crime’s set up, step by predictable step. In order for a set-up like this to work the story needs some revelations for the final act yet Lumet telegraphs the family’s collapse early on and by the time the climax arrives it is both obvious and unbelievable. And who’d believe Philip Seymour Hoffman and Ethan Hawke are brothers to begin with? The actors get in their shots anyway, each occasionally milking the script’s cliches for more than they’re worth, without ever escaping the story’s ordinariness. By the time Lumet finally shakes off his characteristic reserve for the finale’s melodramatic fireworks you can’t help to think the story would have played better on Law And Order., where it would be more energetic, just as shallow and over in half the time.

walking us through the crime’s set up, step by predictable step. In order for a set-up like this to work the story needs some revelations for the final act yet Lumet telegraphs the family’s collapse early on and by the time the climax arrives it is both obvious and unbelievable. And who’d believe Philip Seymour Hoffman and Ethan Hawke are brothers to begin with? The actors get in their shots anyway, each occasionally milking the script’s cliches for more than they’re worth, without ever escaping the story’s ordinariness. By the time Lumet finally shakes off his characteristic reserve for the finale’s melodramatic fireworks you can’t help to think the story would have played better on Law And Order., where it would be more energetic, just as shallow and over in half the time.

***

American Gangster, with its iconic name and its two Academy Award-winning actors sharing the lead, is another film that arrives wearing its prestige on its sleeve. It takes that “American” in the title very seriously; director Ridley Scott is trying to tell us something profound about the country with his true life tale of 1970’s Harlem heroin king Frank Lucas. It just isn’t clear exactly what that something might be.

Frank (Denzel Washington in full movie star mode) learned everything he knew about gangstering by being the valet to Bumpy Johnson (played here by an uncredited Clarence Williams III). Bumpy was complaining about the business world’s disrespect for the middleman when he dropped dead on a chain store floor. Frank takes this as a divine sign to make someone else the middleman as he takes over Bumpy’s Harlem territory. With old-fashioned America ambition, he bucks the Italian mob suppliers and jets to Vietnam himself to become his own importer of pure and cheap heroin.

Scott seems to admire this drug kingpin and it is a little hard to see why. We see Frank commit a few brutal though efficient murders and we see a few nameless junkies die on his product yet in general this portrait of Frank resembles a P.R. profile of a successful CEO: a man shown worth his millions because of his ingenuity and discipline. Frank spouts a lot of business rhetoric, even lecturing a rival on trademark infringement, all the while being a church-going, family-loving pillar of society. Gangster films used to be popular favorites because we could be voyeurs upon people who were gleefully dismissive of the law. Today a gangster like Frank is shown as a respectable stand-in for the world’s business leaders, the Jack Welch of smack. Instead of watching Black Caesar corner a rival in the alley we’re watching Denzel corner his market, something considerably less dramatic.

Steve Zaillian’s muddled script parallels Frank’s story with that of Richie Roberts (Russell Crowe, featuring a  gut), the singularly-focused cop who doggedly uncovers Frank’s operation. Richie, who is mocked and distrusted for being so honest he turned in a million bucks of dirty money to the cops, is presented as if he shares some quality with Frank although it is really hard to define just what that is. Richie is a slob whose private life sucks (he’s another guy suffering with an unreasonable Ex) but somehow he feels he’ll find meaning by bringing Frank down.

gut), the singularly-focused cop who doggedly uncovers Frank’s operation. Richie, who is mocked and distrusted for being so honest he turned in a million bucks of dirty money to the cops, is presented as if he shares some quality with Frank although it is really hard to define just what that is. Richie is a slob whose private life sucks (he’s another guy suffering with an unreasonable Ex) but somehow he feels he’ll find meaning by bringing Frank down.

I’m guessing that British director Scott has as little experience of early ’70s Harlem as I do, so he shamelessly looks to summon the era by copping bits and pieces of everything from Mean Streets, The French Connection and (coincidentally) Lumet’s Serpico and Prince of the City. Atmosphere is something this film has in spades, cinematographer Harris Savides’ desaturated colors nicely evoke our faded ’70s film stock memories. What’s missing within its epic length is a story to support it.

With all of its flailing around for message and scope, American Gangster too often forgets to be coherent. The film is bursting with talented actors who are introduced, given some humanizing bit of business, then left on the sidelines. Neither Frank nor Richie have any confidants to bounce off of, which leaves much of their motives unexamined. The film is also pretty much free of the violent set pieces that are the guilty pleasures of a good mob film. Too vague to realize its literary ambitions, too classy to deliver much violent action, American Gangster glamorizes a dope king’s business acumen while failing to take care of its own business at hand.