PHAWKER: You were, to my mind, the first white rock critic of stature to take rap music seriously. You had that column in Spin back in the mid-80s when Spin really mattered and you were always plumbing the depths of Stetsasonic and Biz Markie and shit. I remember Guccione writing in his Letter From The Editor “is Leland really serious with this rap thing?” What flipped your switch and caused you to sit up and pay attention?

JOHN LELAND: I lived in an apartment on 99th Street [in New York] which was right by the handball court and where there’s a handball court there is a graffiti wall and where there’s a graffiti wall there is MCs and DJs and there is music. And we would just watch these guys dancing on their heads and calling out ‘what’s your Zodiac sign?’ We were suburban snotty punks and we just thought it was exciting to be in a dying city that was producing these two great forms of music: punk and hip-hop.

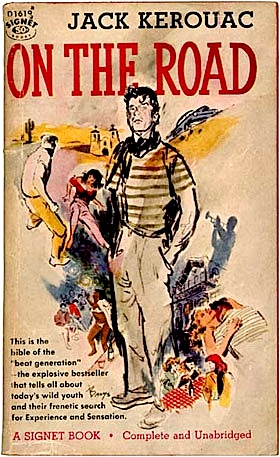

PHAWKER: Your new book is called WHY KEROUAC MATTERS The Lessons of “On the Road.” How many lessons are there exactly in On The Road? More than 10? 344? Less than five? Help me out here.

JOHN LELAND: There is only big lesson, and that is: Forgive everything. It is a message that Kerouac removed from the version of the book we know, but an earlier draft had a character named Red Moultrie that meets God and God tells him “Forgive everything.”

the version of the book we know, but an earlier draft had a character named Red Moultrie that meets God and God tells him “Forgive everything.”

PHAWKER: The subtitle of your book says the lesson of On The Road is ‘not what you think’ — What do people mistake On The Road for?

JOHN LELAND: That it’s a book about adolescent rebellion. When Jack Kerouac wrote On The Road he was 29, he had been in and out of the service, in and out of jail, married once, divorced and married again. He was full-grown man that had seen some of the world and live some. He wasn’t just some wild and crazy guy out looking for chicks and kicks. He was man trying to find his place in the world.

PHAWKER: He seemed to have spent a lot of time living with his mother…

JOHN LELAND: He was married three times, and none of the marriages lasted long and so he would always wind up back with his mother. By my count he lived with his mother in 25 different houses during his life.

PHAWKER: Why is it that he seemed in capable of living the central message of his most famous book — why did he become so bitter and alcoholic at the end?

JOHN LELAND: Most of his life he was miserable, he was a depressive character and that was only made worse by his fame. Also, he didn’t particularly like On The Road — he never thought it was his definitive work.

PHAWKER: Why do you think he so hated the hippies, who were considered, at least by the media, as descending almost directly from the Beats?

JOHN LELAND: He was a little bit like Walt Whitman and the Abolitionists in that regard: Even though he might sympathize with them, he thought they were divisive. Plus he just saw the hippie kids as spoiled and lazy, whereas he saw the Beats as powerful intellectuals producing important work at great personal cost.

PHAWKER: How about you — could you forgive everything?

JOHN LELAND: I wish I could but I tend to think of that as something you spend your whole life moving towards. If I had to write down all the people and things I can’t forgive it would take me up more room than there is online. Al Gore would have to invent a new Internet just to fit all the names. [As told to JONATHAN VALANIA/Illustration by ALEX FINE]

***

John Leland is a reporter for the New York Times, former editor-in-chief of Details magazine, and author of Hip: The History. Treating On the Road as the novel it is rather than the historical artifact it has become, Leland explores the book’s themes of male friendship, traditional family values, and the search for atonement, redemption, and divine revelation in “Why Kerouac Matters: The Lessons of ‘On the Road’ (They Are Not What You Think).”

On the Road 50th Anniversary Celebration

On the Road 50th Anniversary Celebration

Thursday, October 4 (7 p.m.) FREE

A celebration of the 50th anniversary of the first publication of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, featuring a musical performance by Kerouac collaborator David Amram followed by a panel discussion featuring Kerouac’s companion and National Book Critics Circle Award winner Joyce Johnson (Minor Characters) and beat scholar Penny Vlagopoulos; moderated by John Leland, author of Why Kerouac Matters.