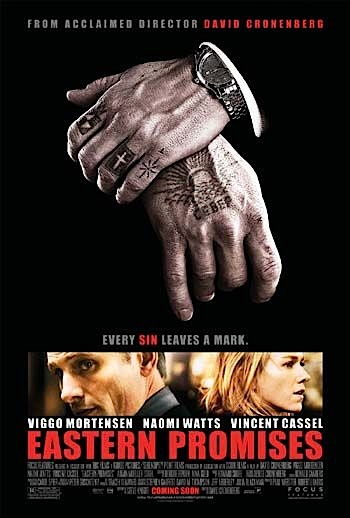

EASTERN PROMISES (2007, directed by David Cronenberg, 97 minutes, U.K.)

EASTERN PROMISES (2007, directed by David Cronenberg, 97 minutes, U.K.)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Except for a few memorable side trips, Canadian director David Cronenberg spent the first 25 years of his career as a feature film maker chronicling his characters’ relationships with reality and their own mysterious and ill-functioning innards. Around the turn of the century he made eXistenZ, whose plot revolved around video games you could plug right into your spine that dissolve reality. eXistenZ seemed to be the perfect summation of all of Cronenberg’s icky preoccupations with guts and the nature of reality. Since then, Cronenberg has turned his back on the type of body horror films that made him a fanboy horror favorite.

Although the director has left the horror genre behind, the question of reality still lingers in his recent films, although his attention has shifted to shifting realities of identity. First he showed us the mental unraveling of mile-high member Ralph Fiennes in 2002’s Spider, then a gangster hiding his past from his family in A History of Violence, and now the shifting loyalties of the Russian mob film Eastern Promises. The transition from graphic horror may have made his films more alluring to mainstream audiences but their dark ramifications still don’t rest easily in one’s mind.

Viggo Mortensen returns after A History Of Violence to play another tightly-wound killer, this one a Russian mob driver named Nikolai. When a pregnant 14 year-old Russian prostitute dies giving birth, maternity ward nurse Anna (Naomi Watts) follows the leads back to Mortensen’s gang, led by the deceptively kind grandfather Semyon (the ever-dependable Armin Stahl-Mueller). When we meet Nikolai, he is gleefully cutting the fingertips off of a dead rival as if trimming cigars, but glimmers of empathy begin to flash across his face and we suspect there is more to Nikolai than can be told by his prison tattoos.

Nikolai’s tattoos play an important part in this story (the film’s promoters even contacted South Street tattoo parlors to hype the film) and even though the symbols etched into his body tell the tale of where he has been, he is still looking for a way to escape his history and do something pure and good. He’s not the only character wishing to escape the roles their lives are forcing them play. Anna wants to give up the search for the child’s family but she is haunted by a miscarriage and her own Russian heritage and Semyon’s son Kirill (Vincent Cassel) is having trouble being his father’s loyal son. Split loyalties propel the story forward until the characters’ contradictions can no longer be escaped.

Written by Steve Knight, Eastern Promises is similar to Knight’s other high-profile script, for Stephen Frears’ Dirty Pretty Things. Like that film Knight writes of unspeakable acts shielded from our view in the closed immigrant societies of modern-day London. Making the gangsters Russian restores a sense of unknowable menace to the genre. Italian-Americans have spent over 70 years as the subject of organized crime films yet by becoming so assimilated into our society they’ve lost the power they once had as menacing “others”; if The Sopranos made any impact it was by showing us mobsters who were now as recognizable as suburban dads, guys just like us. Like the mini-mobsters in the Brazilian crime hit City of God, we know that these mobsters came from situations so untenable that they might find themselves capable of anything. Cronenberg is not afraid to spend time observing the Russian mob’s culture and rituals and it pays off by both making their world seem a little spookily foreign as well as giving an adrenaline shot of freshness to the overworked genre.

And let’s not forget the benefits of having Viggo Mortensen star in your film. I thought his transformation to movie star was going to happen momentarily when I saw him in Sean Penn’s The Indian Runner in 1993 but it was another decade before A History of Violence and The Lord of The Rings trilogy cemented his status as a Hollywood A-list leading man. Being that kind of movie star allows an actor to expand to a mythic scale, a trick that can only be performed for a limited number of times before it takes on the stink of self-parody. That’s why DeNiro’s last mob role was a comedy, not a drama, and why Jack Nicholson’s performance in Scorsese’s’ The Departed was so frequently cited as “distracting” by critics.

If Mortensen had become a star a decade ago I doubt he would have been as startling as he is here. Nikolai, like his country of origin, seems to have survived a complete collapse. In selling his usefulness to the crime family, he coldly says “I am dead already, now I live in the zone all the time.” The clues of his humanity are fleeting and few, and you find yourself studying those sunken eyes waiting for a glimmer. Like History of Violence, Eastern Promises has one indelible violent outburst and it’s a dandy that’s sure to fall into crime film legend (other critics have named it but I hope it hits you as freshly as possible) and the Iggy-taut Mortensen makes the most of this horrifyingly visceral moment.

What has been missing from this latest phase of Cronenberg’s career is the ambiguities that lingered after his stories ended, conspiracies that may or may not be true or diseases still raging during the final credits. Eastern Promises still gives audiences a little more closure than they probably need yet when a filmmaker delivers a film this masterful and fresh so late in his career at least Cronenberg’s future itself is excitingly indeterminate.