BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC SAN FRANCISCO — As Philly slowly melts into its mid August stew I slipped off this week to San Francisco, where it is a good twenty degrees cooler and I can lounge around in my sweater all week and entertain some thoughts other than, “Geez, it’s frigging hot today.”

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC SAN FRANCISCO — As Philly slowly melts into its mid August stew I slipped off this week to San Francisco, where it is a good twenty degrees cooler and I can lounge around in my sweater all week and entertain some thoughts other than, “Geez, it’s frigging hot today.”

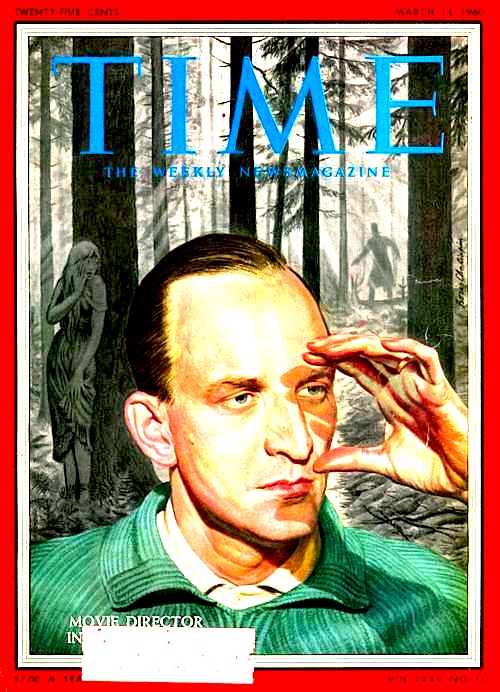

The plan was to relax and maybe file some wildly irrelevant pieces on the Pacific Film Archive’s Max Ophuls festival or Alpha video’s reissue of Jean Hersholt‘s Dr. Christian series. Instead, my ride to the airport arrived with the news of Swedish director Ingmar Bergman‘s death, followed and a day later by Italian auteur Michelangelo Antonioni. Each is deserving of an extended homage, they’re the type of film artists we will never see again but I worry I’ll ruin my vacation mindset if I’m forced to dig too deep into just what makes their dark and mind-wrenching visions so singular. Still, if my kid grows up to ask what I was doing when Bergman and Antonioni died I better have something to show for it, so margarita in hand, here I go.

When people want to satirize difficult and heavy foreign films of the middle of the twentieth century they often just parody Bergman’s somber and stark black and white classics (SCTV did a hysterical parody piece bit with a perplexed Count Floyd hosting the Bergman-esque “Whispers of the Wolf”. “You think it’s not scary to be depressed?” the Count bellows.) It was this kind of mild disrespect that gave me the misplaced confidence to confront my college film professor after a watching Bibi Anderson and Liv Ullmann’s heads collide in a screening of Persona and complain that Bergman was a fraud, a charlatan whose vagueness (or at least what seemed vague in my thick skull) conned intellectual film goers into believing something heady was just witnessed. Today it is an excruciating memory of youthful wrong-headedness.

When people want to satirize difficult and heavy foreign films of the middle of the twentieth century they often just parody Bergman’s somber and stark black and white classics (SCTV did a hysterical parody piece bit with a perplexed Count Floyd hosting the Bergman-esque “Whispers of the Wolf”. “You think it’s not scary to be depressed?” the Count bellows.) It was this kind of mild disrespect that gave me the misplaced confidence to confront my college film professor after a watching Bibi Anderson and Liv Ullmann’s heads collide in a screening of Persona and complain that Bergman was a fraud, a charlatan whose vagueness (or at least what seemed vague in my thick skull) conned intellectual film goers into believing something heady was just witnessed. Today it is an excruciating memory of youthful wrong-headedness.

Too many people are led to Bergman early, before their personal experience can make sense of the philosophical questions about life, death and relationships his filmography wrestles with in masterpiece after masterpiece, though even at this young age something had planted a seed in me. Like a repressed homosexual who feels so disgusted he hangs out constantly in the gayborhood, I kept borrowing Bergman’s videos from the college’s film department, looking for some sort of proof of the fraud he was perpetrating on the filmgoing public. Finally it was Wild Strawberries, perhaps his most accessible and optimistic meditation on death that unlocked the key to understanding Bergman’s method, as it slowly shifted between the horror movie nightmare of finding one’s body in a coffin to the sweet-natured final memories of a quiet afternoon at the lake. Another fifteen years passed and I found my perceptions of his films changing again, the brutally honest relationship in Scenes of a Marriage (has anyone ever matched the vivid performances as Ullmann and Erland Josephson?) is something I had to project myself into in my twenties, in my thirties it was something I could reflect upon. Even the films I thought I had grasped as a young person revealed themselves as radically different seeing them years later and I’m counting on the fact that Bergman’s work will stay one step ahead of me when I watch them twenty years from now as well.

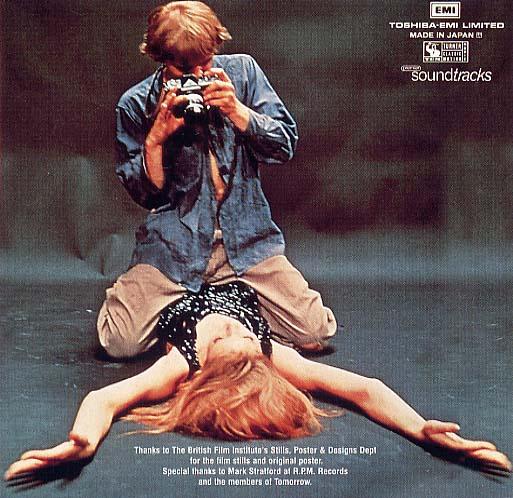

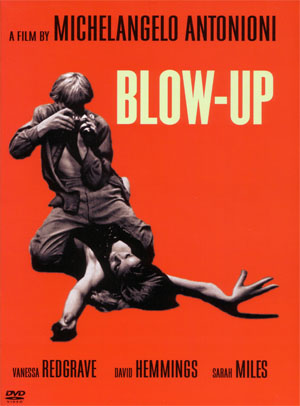

Thankfully I was able to catch as rare retrospective on Antonioni’s work in the late nineties at San Francisco’s Castro Theater where seeing stars like Monica Vitti and Marcello Mastroianni projected at heroic heights gave their fatalistic ennui the glamour of doomed film noir figures, the weight of their discontent growing so vast it squeezed the criminal plots right out of the story and just left the despair. I was recently reminded of the ending of 1962’s L’Eclisse, where neither of the two badly matched lovers keep their promise to meet at the fountain at noon, during the climax The Sopranos of all things, where keeping Tony’s whacking off-screen similarly thwarts our expectations (You all know he gets whacked, right?).

gets whacked, right?).

By this point I had become the elder statesman demanding younger viewers track down and try to absorb the challenging, uncompromising work these twentieth century giants created and there were plenty of young eager film fans who assured me that their work had been rendered irrelevant by times passing.

And who knows, maybe they’re right. Bergman and Antonioni had absorbed philosophy and literature, and invented cinematic language that merged and transcended their forms. Today it isn’t readily apparent that most modern director even read. If Bergman and Antonioni are failures in any sense it may be that their revolutionary work, which once galvanized the world, has found so depressingly few disciples in modern cinema. Seems like truth and the search for it doesn’t have the currency it once had.

– – – – – – – – –

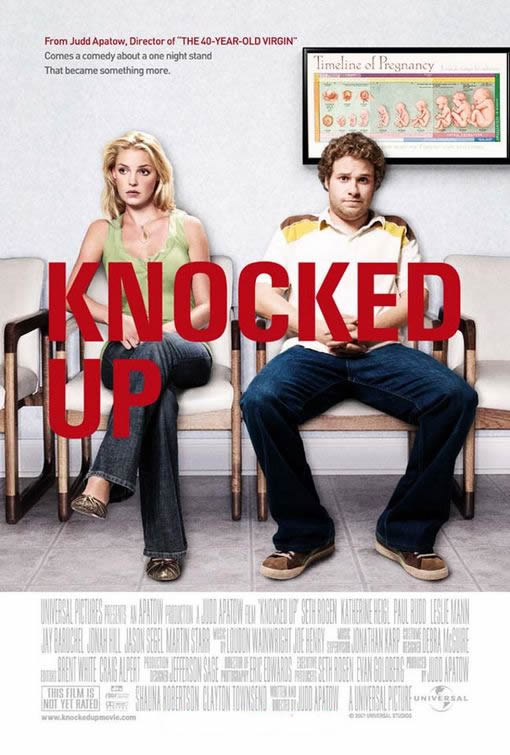

In an effort to escape another mundane evening at the in-laws house I managed to sneak off to a late evening showing of Knocked Up, still lingering on a few small screens. Luckily, I laughed my ass off or I might have been put off by the glaring gaps of logic that shouldn’t go unnoticed. Part nerd boy romantic fantasy (unemployed internet porn mogul wannabe lands E! Entertainment Television interviewer? Could happen…) and part supposedly insightful look at the guy/girl thing, Knocked Up often seems as clueless about women as the dopey everymen it chronicles. When their drunken fling leaves goody two-shoes Alison (Grey’s Anatomy’s Katherine Heigl)  preggers she sets about to develop a relationship with the vaguely sweet-natured doofus Ben (lovable teddy bear Seth Rogen). “I never even thought about what it would be like to have a baby” she says, something that would have to cross the mind of any ten year old girl, let along someone in her mid-twenties who lives in her sister’s home with her two nieces. The fact that she didn’t notice missing her period till the second month and that she immediately feels she has to confer with the guy she met once and hasn’t talked to since he unleashed a offensive barrage of tits and bush jokes, seems counterintuitive at best. Little points like this continue to pile up; when it comes to portraying the inner lives of women, screenwriter/director Judd Apatow seems to be as accurate as Ratatouille is about the eating habits of rats.

preggers she sets about to develop a relationship with the vaguely sweet-natured doofus Ben (lovable teddy bear Seth Rogen). “I never even thought about what it would be like to have a baby” she says, something that would have to cross the mind of any ten year old girl, let along someone in her mid-twenties who lives in her sister’s home with her two nieces. The fact that she didn’t notice missing her period till the second month and that she immediately feels she has to confer with the guy she met once and hasn’t talked to since he unleashed a offensive barrage of tits and bush jokes, seems counterintuitive at best. Little points like this continue to pile up; when it comes to portraying the inner lives of women, screenwriter/director Judd Apatow seems to be as accurate as Ratatouille is about the eating habits of rats.

Add to this endless product placement, E! Channel highjinks and characters endlessly repeating dialogue from 80’s blockbusters and Knocked Up seems a bit too much like real life: overstuffed with advertising and celeb culture trivia in places where ideas should be. I’m not one to let personal politics interfere with a good time, like I said the film is full of genuine guffaws and charming performances from it’s all-too real looking cast of dorks (the men that is, the women of course are all stone foxes), yet in other ways it seems like a painfully unselfconscious picture the social life of the Aint-It-Cool set. That’s not to accuse it of being dishonest, since Apatow has made two TV series and two films examining how boys find girls indecipherable I’m starting to believe he really doesn’t have a clue.