[Artwork by JENNIFER LUI]

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Years ago I went to a party where esteemed film critic David Thomson was scheduled to attend. Before his arrival the host announced “He’s a fascinating guy, but he doesn’t want to talk to anyone about film.” “Send him home,” I remember thinking to myself. It’s like attending a party with Red Barber and not being about to bring up the subject of baseball. Since I’ve been writing about film for a few years now I see his point. Being introduced as a film critics is a conversation starter that doesn’t always lead to scintillating discussion and as often as not it leads to the question “So what’s the greatest movie ever made?”

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC Years ago I went to a party where esteemed film critic David Thomson was scheduled to attend. Before his arrival the host announced “He’s a fascinating guy, but he doesn’t want to talk to anyone about film.” “Send him home,” I remember thinking to myself. It’s like attending a party with Red Barber and not being about to bring up the subject of baseball. Since I’ve been writing about film for a few years now I see his point. Being introduced as a film critics is a conversation starter that doesn’t always lead to scintillating discussion and as often as not it leads to the question “So what’s the greatest movie ever made?”

Don’t people hate critics because they think they have answer to that question? Of course there is no real answer to that question, Citizen Kane be damned, but even if I don’t have the correct answer to the question I do have a suitable one. The Wizard of Oz. Who’s going to argue? It’s got outrageous set design, everyone in it is amazing, it zips along and best yet it carries no snob factor. And I’m not even factoring in the Pink Floyd thing.

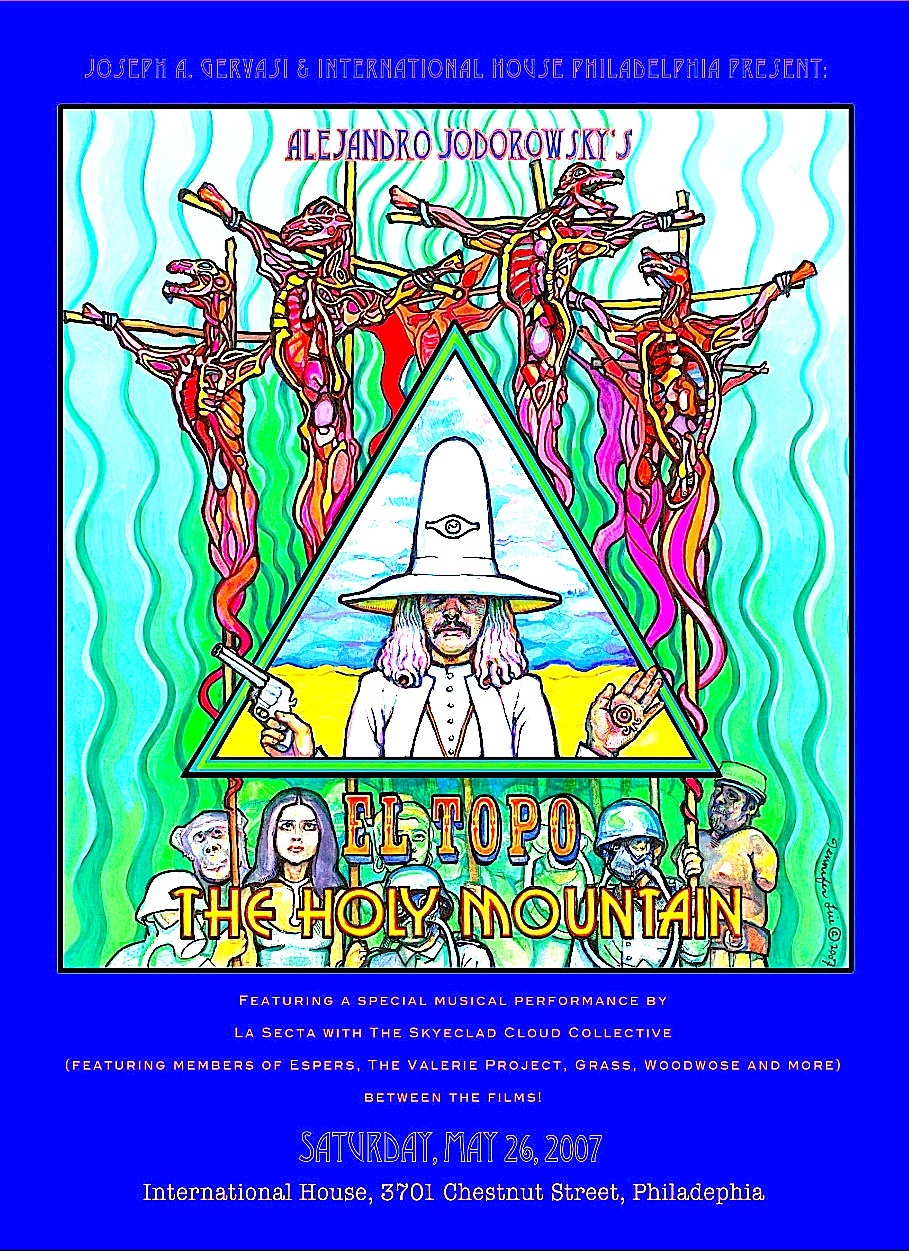

Which is why you should drop everything and head down to the International House to see the double feature this Saturday of Alejandro Jodorowsky’s surrealist cinema classics, El Topo and The Holy Mountain, because these long-unavailable features from the early-seventies are very much like the greatest film ever made. Jodorowsky’s work may more directly reference the phantasmagorical films of Fellini, Bunuel, Godard and Sergio Leone yet when I coincidentally saw Oz and El Topo back-to-back I was surprised by the similarities – the mystical journeys of enlightenment, the vivid colors and the seemingly inexhaustible string of hallucinogenic characters and situations that flow forth from the screen. And let’s not forget dwarves, dwarves, dwarves! El Topo and The Holy Mountain are both heady experiences that aim for experiences few films dare and it is a cinematic trip you should travel at least once.

The legend of these films is nearly as wild as the films themselves. The director was the brilliant and self-promoting Alejandro Jodorowsky, an Russian Jew whose family escaped the Cossacks and settled in Chile. As a young man he hopped between Barcelona, Paris and Mexico City, where like Welles he became the master of a few mediums, including poetry, theater and literature. In 1968 he was based in Mexico City when his debut feature Fando and Lis caused a riot at a local festival leading to interest in funding his second film, a metaphysical western titled El Topo (The Mole). Jodorowski arrived in NYC with a print of El Topo in the fall of 1970 and got it booked into Chelsea’s Elgin Theater, where its nightly midnight show regularly sold out (initiating the trend of counterculture midnight films) and it soon attracted the recently ex-Beatle John Lennon to bask in it’s profundity. Lennon proclaimed it a masterpiece and had the Beatles business manager Allen Klein scoop up the rights, with John and Yoko later supplying Jodorwsky with the $750,000 needed to finance his next film, The Holy Mountain.

The rights to both films ultimately landed in Allen Klein possession. Klein has been notorious for refusing to reissue the many recordings his ABKCO company held the rights to, waiting well into the CD era before he allowed issue of Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound hits, Sam Cooke’s productions for the SAR label and the entire catalog of Philadelphia’s Cameo Parkway label. A long-simmering fued between Jodorowsky and Klein has similarly kept these films unavailable to theaters and to home video until 2004 when the cantankerous duo finally buried the hatchet and paved the way for El Topo and The Holy Mountain’s resurrection.

Fitting, since resurrection plays a central role in El Topo, the story a mystical gunfighter (Jodo himself) who, like the mole in the opening parable becomes blinded while seeking the light. It’s pure Lady MacBeth (woman get a pretty bum shake in Jodorowsky’s world – either shrews, whores or crippled saints) when El Topo’s woman Mara goads him into facing down the four master gun fighters. The lesson he learns in conquering them leads to his breakdown and attempted repentance. The Holy Mountain brings things to a grander scale. Here Jodorowsky plays The Alchemist, a leader who introduces a common thief to the seven most powerful people on the earth, who together plan to learn the secret of immortality and lead the world to peace (you can see how he shook the money out of John & Yoko with a premise like this). Jodorowsky lets his globetrotting curiosity flow freely from these films, working in bits of ritual and pan-religious philosophy from all parts of the world, then pouring a surreal syrup over the mix. Again like Oz, these fantastic, nonsensical details continue to arrive scene after scene and they leaven all this conscienceless-raising with jolts of visual poetry and crude humor. Birds fly from gunshot wounds, people make love to giant metal vaginas and a man works years to compile of collection of one thousand jarred testicles. It may not be Oz but it’s sure to be banned in Kansas

So after thirty-odd years wandering in the wasteland how do these films hold up? Shockingly well. The film’s restoration completely changes the character of the films, the bootleg’s sun-bleached colors transformed into the bright palette seen in expensive Hollywood pictures of the day. Both films deal with self-consciously iconic characters who stand for ideas and states of being as much as “real” people and their cartoony colors give them a vivid punch like the comic book heroes that are a part of Jodorowsky’s cultural stew (he writes comics himself and at one time was rumored to have the largest collection in South America). There is a New Age-y earnestness to the film’s mix of religious ideas that hint that these films could only be made in the 1970s but the film’s lack of faddish details (not a single psychedelic camera trick is used) and their reliance on rocky, desert landscapes go a long way to giving Jodorowsky’ film’s a timeless air.

When The Holy Mountain failed to find a breakthrough audience Jodorowsky seemed to have lost his way, spending time trying to mount the first version of Frank Herbert’s Dune (it would have starred Orson Welles and had Salvador Dali contributing to the set design) and making only three more films, all but 1989’s Santa Sangre seeming like compromised work (he’s currently reported to be in production on a new film in Mexico with Marilyn Manson and Last House on the Left’s lead creep Daivd Hess). Yet if Jodorowsky never makes another movie his impact has already seemed to seep into the subconscious of mainstream film, recognizable in Star Wars fusion of ethnic design and mythic tropes, and The Matrix’s zen blatherings. In his seminal book Midnight Movies Jay Hoberman describes Holy Mountain’s climax as being “hackneyed, though felt”. It’s that sense of feeling, of irrational passion, that Jodorowsky injects into these two mind-blowing epics that makes all the difference.

P.S. No small plus is the fact that La Secta with The Skyeclad Cloud Collective (featuring Greg Weeks of the Espers) will be performing some suitably trippy sounds between films.

EL TOPO (1970, directed by Alejandro Jodorowsky, 125 minutes, Mexico)

THE HOLY MOUNTAIN (1973, directed by Alejandro Jodorowsky, 114 minutes, Mexico)

Double Feature! Saturday Night 7:30 pm At the International House (3701 Chestnut)