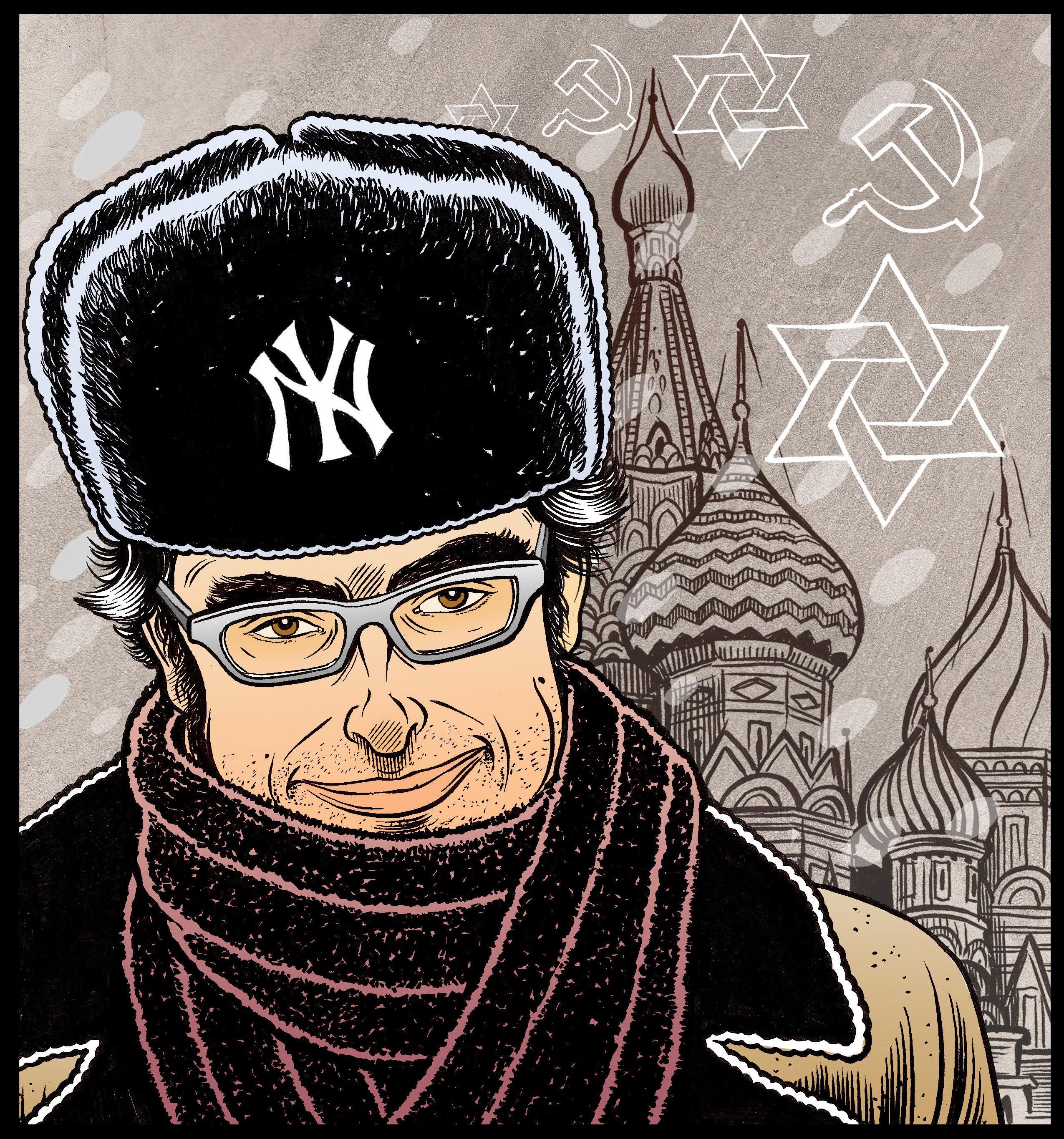

[Illustration by ALEX FINE]

BY MAVIS LINNEMANN BOOK CRITIC Gary Shteyngart’s second novel, Absurdistan, is a biting comical ride in the adventures of Misha Vainberg, the 325 lb. son of the 1,239th richest man in Russia. After attending Accidental College, USA, and living in the South Bronx with his hot Latina girlfriend, Misha must return to Russia to see his father. When his father kills an Oklahoma businessman, Misha can no longer obtain a visa from the INS. Misha’s love for New York and multiculturalism take him to the little-known country of Absurdistan, were he’s supposed to get a Belgian passport. Instead, civil war breaks out and Misha’s stuck in the middle of it. Absurdistan is a laugh-out-loud satire of America, oil and foreign relations. Shteyngart, who will read at 5:30 p.m. today in the Skyline Room of the Central Library as part of the Philadelphia Book Festival, talked to Phawker about the perils of writing Absurdistan after 9/11, fat-man fiction, his new book, and what it’s like to be a writer in a world where literature is dying a slow but steady death.

BY MAVIS LINNEMANN BOOK CRITIC Gary Shteyngart’s second novel, Absurdistan, is a biting comical ride in the adventures of Misha Vainberg, the 325 lb. son of the 1,239th richest man in Russia. After attending Accidental College, USA, and living in the South Bronx with his hot Latina girlfriend, Misha must return to Russia to see his father. When his father kills an Oklahoma businessman, Misha can no longer obtain a visa from the INS. Misha’s love for New York and multiculturalism take him to the little-known country of Absurdistan, were he’s supposed to get a Belgian passport. Instead, civil war breaks out and Misha’s stuck in the middle of it. Absurdistan is a laugh-out-loud satire of America, oil and foreign relations. Shteyngart, who will read at 5:30 p.m. today in the Skyline Room of the Central Library as part of the Philadelphia Book Festival, talked to Phawker about the perils of writing Absurdistan after 9/11, fat-man fiction, his new book, and what it’s like to be a writer in a world where literature is dying a slow but steady death.

Phawker: You’ve gotten a lot praise for Absurdistan and The Russian Debutante’s Handbook. How do you deal with the pressure when you’re writing?

Gary Shteyngart: I was so freaked out over the second book because [they] usually say the sophomore slump will follow. I was very afraid. I moved to Italy for a while to write the second book. I wanted to be away from it all — the pressures. I thought the second book was going to be such a disaster that I didn’t want to be around English-speaking people. I wanted to become an Italian and avoid the shame. I really had very low expectations. I always have low expectations — even for the third book.

Phawker: Will the pressure be even greater for your third book?

GS: Maybe. Disaster must strike at some point. I have very Soviet-Jewish genes so I’m disaster prone. I’m always prepared for the worst.

Phawker: I read that you started writing Absurdistan a few days before 9/11.

GS: It was a few weeks or month, but it was right around that time. I remember I ‘d come back in August from doing my research of the former Soviet Union, the parts where Absurdistan is set. I think I started a week or two later.

Phawker: Did you have to put the writing of it on hold?

GS: Everybody was freaking out, every writer. The general feeling was, “What the hell are we doing writing?” It just felt like more monumental things were happening in the world and what we were doing was so insignificant. I do think that 30 or 40 years from now, when people will be looking at what happened around this time in American history, I think, in many ways, it’s not going to be the nonfiction books that stand out. When people want to know what people were thinking about and how life was, I think they’ll look towards the fiction.

Phawker: Why do you think that is?

GS: Well, because I think that nonfiction can get the facts down pretty well. I think that nonfiction is very good at giving the background. But what fiction does — good fiction, anyway — it really allows us to inhabit the mind of people, of individuals, who lived through 9/11, who were there before and what happens afterwards as well. I think certain films, certain movie series, certain television series, certain books will be our path to understanding what America was like at the turn of the century.

Phawker: What book or TV series do you think best illustrates this era?

GS: Oh “The Sopranos.” It’s like reading a 19th century novel or something. It’s like reading Flaubert when you get introduced to the characters of the mayor and the farmers. It’s just beautiful panorama, and frightening too. He really captures the nuances of everything that’s going wrong in America, the corruption in American society. Tony always says: “Things are trending downwards.” That’s how he describes organized crime. In many ways, it feels like America in the past five, six years has not been doing as well as it has in the past. It’s lost some of its mission. People bandy around words like “freedom” and “liberty” all the time– the “freedom tower.” It seems like they’re grasping for something that maybe feels like it’s no longer there. “The Sopranos” is a fabulous show and I think of it in novelistic terms. A writer can do much worse than view that show and especially, listen to the dialogue. Obviously, these wonderful actors bring it to life. There”s some ingenious, ingenious writing that’s as good as any novel.

Phawker: When did you pick up writing Absurdistan again after 9/11?

GS: Maybe a month later. It didn’t take long. I can’t remember because that whole era is pretty muddled in my mind. I sometimes write diary entries and I remembered not doing any of that just, being floored.

Phawker: You live in New York, right?

GS: I live in New York. I saw it happening from my roof. I had a girlfriend who lived in Midtown, so I went and stayed at her place. She had an apartment which didn’t really face anything, just a wall, so that kind of the subterranean feeling really fit the mood. I retreated from the world for a week or so, as did many other people. That’s the thing about writing. I need to write. Pretty soon, a month later, I was writing Absurdistan. Absurdistan, the way it was conceived — I had already started writing it — had some scenes towards end of the book where an entire city is destroyed. I thought “Oh my God, how am I going to write this?” But it was planned out before 9/11 and I was very worried about writing something like that after 9/11; but in a weird way for a lot of the thing that I was writing about, there was a kind synchronicity with what happened later on in terms of Iraq, and Halliburton especially. So as I was writing it, life began to imitate life a little bit. And I wish it didn’t for the sake of the country, but not for my own fiction. So that was very strange to write at that time.

Phawker: What was it that prompted you to write this novel?

GS: A bunch of things. There’s a tradition, in Russians, up in Leningrad and Moscow, they’re obsessed with the Caucasus because it’s a warm beautiful land, especially Georgia. I would go there as a child and some of the most beautiful works in Russian literature are set there. My college thesis was partly about that region. So I always wanted to go back and I did go back and I found — in a lot of these countries, to be there were oil booms and a great deal of corruption. At one point, a hooker actually asked me if I was I was from Halliburton, “Golly Burton,” as they say in the book. The book can be seen in some ways as an act of journalism because some of it actually did take place to an extent.

Phawker: What did you say to the hooker when she asked if you worked for Halliburton?

GS: I told her I was a Russian writer and she just spit on the ground. She really hates Russian writers. And that made it into the book.

Phawker: You take a stab at Cheney and the oil industry in Absurdistan. Has Cheney or others involved with KBR or Halliburton commented?

GS: No, I think in Houston it went over pretty well.

Phawker: How did you decide on the Accidental College, USA?

GS: I was thinking of my alma mater, Oberlin College. Its location makes it seem like kind of an accident. Also there’s a college called Occidental College in L.A., which this book isn’t about it at all, I just like the way it sounds — Occidental, Accidental.

Phawker: So did your experiences at Oberlin effect that at all?

GS: Oh absolutely. That school just keeps on giving. It was such a loony place; often in a good way — some of my favorite scenes in Absurdistan take place briefly in Accidental College. I’ve enjoyed writing about those days. It’s so hard to remember what happened. It was all seen through this filter of pot smoke — 6-foot bongs and whatnot. It was the first time in my life that I really relaxed a little bit. Partly, because of all that pot smoke. It was a very different from the kind of immigrant pressure cooker in New York. For me, it was my first exposure to people who didn’t want to make a killing being investment bankers, or lawyers and doctors and whatnot. It was an experience.

Phawker: Would you ever live in the Midwest again?

GS: No. Philly is the one place I could live in outside of New York, because it’s so close, and the food is great and the prices are good. Somebody in New York Magazine called it the “Sixth Borough.” I don’t know if you guys think of yourself as that.

Phawker: I haven’t lived in Philly for very long, but I don’t think Philadelphians like that too much.

GS: Probably not. But Philly is a nice town.

Phawker: You’re always poking fun at Misha’s attitude towards multiculturalism. What’s your attitude towards multiculturalism?

GS: I’m incredibly multicultural myself. I live in a building that has the three things necessary for diversity, the three Hs: Hassidic, Hispanic and hipster — I’m really into diversity. Misha, on the other hand, is quite into diversity but for all the wrong reasons. He doesn’t really understand what it means. It’s just something he heard a lot at Accidental College and he’s in love with a girl from the South Bronx. She is the stand-in for his multiculturalism. When he talks about diversity, it’s just a way for him to escape from the horrors of his own background; it’s Russian and Jewish and it hasn’t worked out for him too well, as in the circumcision scene. I think he is very much looking for something and multiculturalism is the answer to what he’s looking for.

Phawker: Why did you decide to use the really kind of horrifying circumcision scene?

GS: It’s usually the scene I read, too. I want to be honest with you. I figure if you can take that scene then you can buy the book and read the rest of it. A lot of Soviet Jews were circumcised quite late in life, when we came to this country. It wasn’t always pretty. The book does take a kind of skeptical attitude towards religion, Judaism, Christianity and even Islam sometimes comes in. The idea of the father wants this; the son doesn’t want this. This is the father imposing his will on the son and the results are not good. In some ways, it’s more about the relationship between the father and the son than it is about the actual act. In the scene leading up to it, is a long discussion between the father and the son about why he has to do this. In a way, a lot of the characters in this book are trapped in ethnic and religious circumstances that they didn’t call for. What’s so interesting about going around the world is that people are just trapped in these awful circumstances. In some ways, they all filter back to national and religious grievances. I think that’s really the heart of this book is a person trying to overcome all that and live in what he thinks is a normal world, which he thinks is the South Bronx.

Phawker: Is that reflective of your own experience?

GS: Yeah, to some extent. I’m a very secular person and I really don’t care about nations. The more I travel around the world, the more I really see the commonalities in people despite the fact that people obviously grew up in various kinds of societies, some capitalist and some not, some Catholic. In the end, I think the basic desires of people are quite similar. I really do believe that the less stress we put on where we came from, the better it is for the future of this quite in-peril planet.

Phawker: Where did Misha’s character come from?

GS: A lot of it comes from observing people. I’ve always been fascinated by large individuals and I’ve always been fascinated by “fat man fiction,” so to speak — I was asked by the New York Times to pick the best novel since the 1980s and I picked the Confederacy of Dunces. It’s a masterwork, a masterwork in capturing a character so honest. Toole is so honest in describing him. He’s using comedy but letting tragedy shine through underneath. At the same time, what an amazing portrait of a city, New Orleans. That’s the kind of fiction that I most enjoy, that’s rooted in not just the character, but also in a sense of place and time.

Phawker: Well, it also seems that Misha gets laid more often than Ignatius ever did.

GS: When I was writing about Misha, I was also listening to a lot of Notorious B.I.G. There were a lot of really fat rap stars that seemed to be getting a lot of action. Misha tries to rap, quite badly too, so I was thinking “Geez, here I am just a tiny little man and here are these men four times my size — they’re doing quite well out there.” So I wanted to celebrate fat-man lovemaking, which in America, that’s just about half the population. I’m really writing for a large, no pun intended, audience.

Phawker: Did you have a lot of fun writing the raps in this book?

GS: I had fun writing most of this book. As I was having fun writing it, I was feeling incredibly guilty because I was thinking this can’t be a good book if I’m having this much fun writing it. I was living in Italy, so I’d venture out into the street and I’d basically be in my own mind all the time. It’s always helpful to live in a country where you don’t quite know the language. In some ways, that really focused my mind on the English and on the Russian too.

Phawker: Do you visit Russia often?

GS: Every year. I came back from a very long trip to these countries with about 300 pages of notes. A lot of what I do is research. I try and do a lot homework on everything I write. In effect, there is a kind of bridge between fiction and nonfiction and I think it’s important for novelists these days to go out there, to see the world, because that’s what novelists have always done. There’s room for a kind of interior novel but I think also its very good to know what the world is like, because America is only a part of it.

Phawker: Do you drink lots of vodka?

GS: I drink a fair about. All I have in my refrigerator is vodka. I don’t know how to cook. Eight bottles of vodka and nothing else. It’s a bad statement, but good vodka, very good vodka.

Phawker: I hear your new novel is going to feature Jerry Shteynfarb (a minor character, and Misha’s foil in Absurdistan).

GS: Not exactly. A little bit, not much. His role is not as grand as I had envisioned. It’s set in New York, not in Albany. It’s about immortality. It’s about people forgetting how to read and write. Maybe it’s not about fiction after all.

Phawker: Can you give us a little teaser?

GS: It’s about a love affair of two immigrants from different cultures in a New York that’s slowly falling apart, an America that’s slowly falling apart. There’s an elite of people who are, I can’t even go into it, it’s so complicated, but who don’t die. No death. It’s about the yearning of one of the characters to achieve this kind of immortality. It’s gonna be strange.

Phawker: Why did you decide to use Jerry Shteynfarb, a name so similar to your own?

GS: I wanted to have little fun with a kind of doppelganger. Shteynfarb does all the things that I can’t do. He’s kind of a rogue and he really uses his immigrant credentials to kind of ride this wave. It’s a chance to experience schmuckhood through another character.

Phawker: When do you think it will be out?

GS: Hopefully, two or three years.

Phawker: How often do you write everyday?

GS: Three to four hours a day

Phawker: Everyday?

GS: Except Sunday. Sunday is my day to frolic.

Phawker: How do you feel about being a writer in a world in which literature is dying medium?

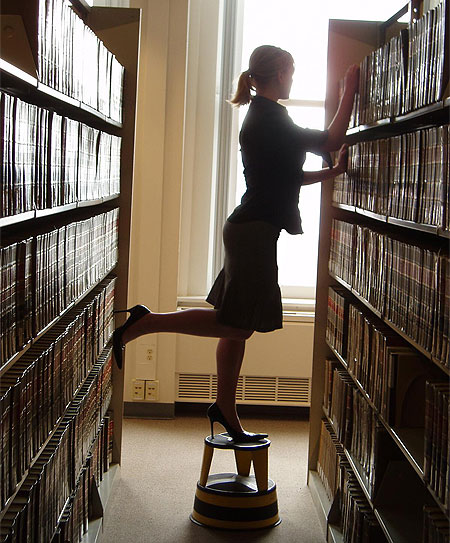

GS: It is a dying medium. It’s so strange to know? I think it was Franzen that said, “Fiction is the new poetry,” in terms of people not being part of the central cultural discussion. I don’t know. What can you do? I’m very fortunate to have a sizable audience. But I think it’s a gloomy picture in terms of publishing right now and people having the time and inclination to really inhabit the mind of somebody else. It’s much easier for people to look at snippets of information on the Internet or watch some nonsense. We’re in a world where people talk about advertisement more than they talk about fiction. [They’re] more interested in the GEICO commercial rather than in what Norman Mailer has written. It’s very scary and that’s one of the things my new book is dealing with, the decline of the literary culture and what that means. Nowadays, people are running around and people read most of their books on airplanes — and we live in a very visual culture. I’m very happy with book clubs, those have been very helpful. What’s interesting is that, most of the readers these days are women. Oprah probably has something to do with this, but boys don’t read so much and that’s really strange. Women consume everything, written by women, written by men. All kinds of serious fiction. It’s all in the hands of women.

Phawker: Do you think Jewish people are funnier than Gentiles?

GS: I’ve known so many hilarious Gentiles. I think Jewish humor is the one I feel most at home with because in some ways, its sort of humor from the edge of the grave, its very morbid, existential humor. I think that a lot of Korean Americans, for example, I think their humor has some of a similar twang to it, coming from a nation that doesn’t have a happy history. Although, I don’t think it’s entirely true that one country is funnier than another.