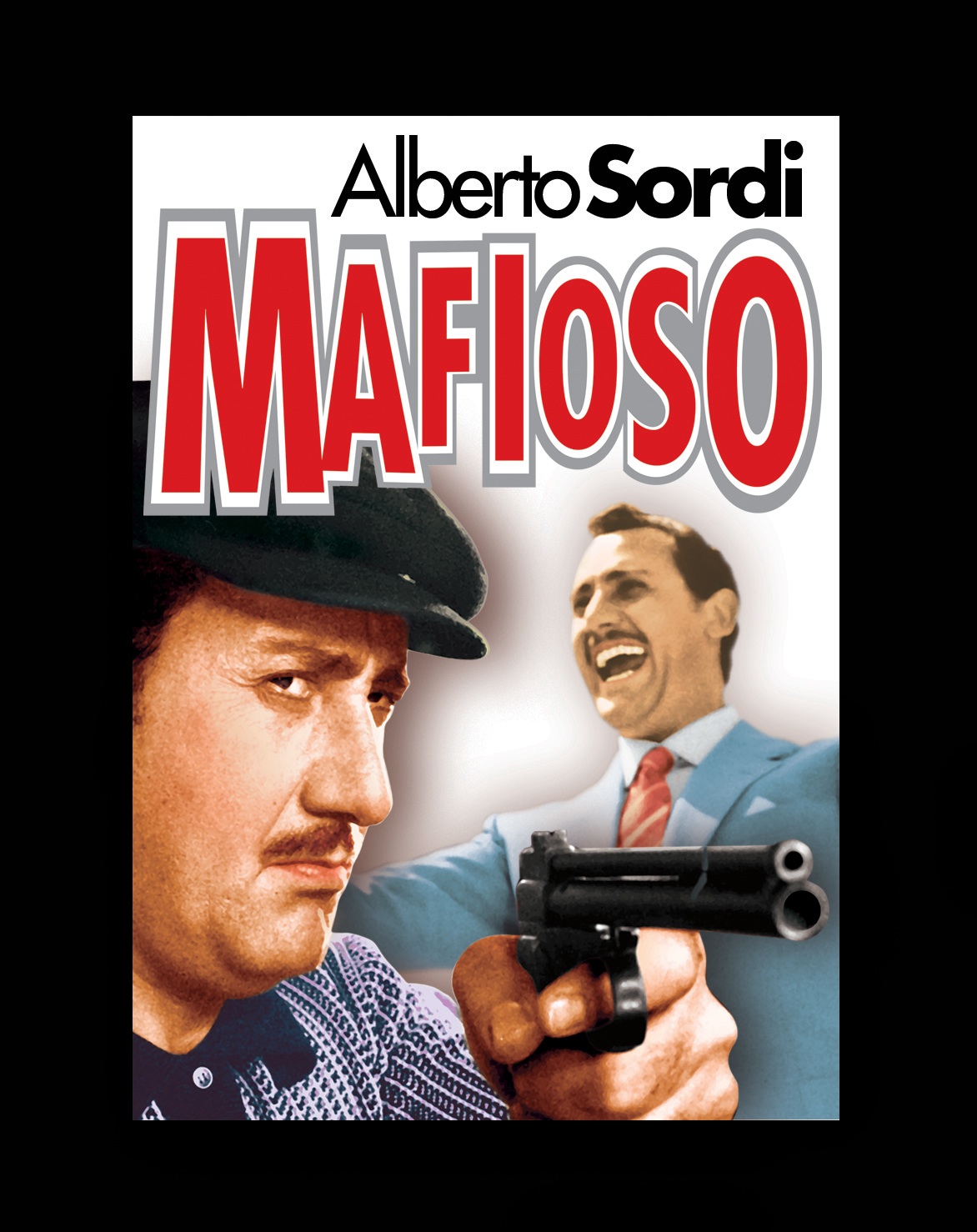

(1962, directed by Alberto Lattuada, 105 min., Italy)

(1962, directed by Alberto Lattuada, 105 min., Italy)

BY DAN BUSKIRK FILM CRITIC

There was quite a lot of grumbling last year over the fact that many critics listed Jean-Pierre Melville‘s 1969 war film Army of Shadows as the best film of 2006, as it was getting its first U.S. screenings 37 years after it was made. Resurrected by the small distributor Rialto Pictures and it honestly was like nothing else seen in theaters last year. This year, Rialto is setting its hopes on another forgotten gem, Alberto Lattuada’s 1962 tragic-comedy Mafioso. While it’s not as stylistically daring as the quiet and tense Shadows, Mafioso is marvel of character-driven storytelling — a proto-Mob flic that is sure to be one of the richest cinematic trips you’ll take all year.

Lattuada is best known for co-directing Fellini‘s 1950 debut Variety Lights, and here he has such deft control of the film’s shifting tone that it makes one wonder what other masterpieces might be lurking in his resume of 30-odd films, none of which are readily available in the U.S. In Mafioso, popular Italian comic actor Alberto Sordi plays Antonio, a bit of a dandy who is a husband, a father and nut-busting boss at an auto plant in Milan. The workaholic allows himself the rare vacation in order to bring his sexy wife and his two little blonde girls to the earthy village in Sicily where he was raised. Antonio is the quintessential city guy who has left his country roots behind, and it’s semi-embarrassing to watch him alternate between playing the happy peasant to impress his wife and then switching gears to play big shot to his disbelieving Sicilian clan.

Sordi plays this with the comic timing of a young Peter Sellers, and the film would have distinguished itself if it just let the character of Antonio bumble around among the annoyed village folk. When Antonio meets up with the local Don, all the goofiness dissipates and Antonio’s story heads down a darker path, with the still-chatty native son being the last one to realize how grave his situation has become.

Dropping all restraint, I’ll just come out and gush that “poetic” is the only word to describe the seemingly effortless craft Lattuada exudes in telling this story. He peppers this trip to the beautiful and foreboding Sicily with a number of seemingly anecdotal details: a party spilling around a corpse in a casket; Antonio’s sister’s thick mustache; Antonio’s wife stopping the dinner dead when she scandalously light a cigarette. They’re telling, yet seemingly random little moments, but only when the film reaches its climax (a perverse and unexpected moment right out of a Sopranos episode, filmed nearly 40 years earlier) do we realize that Lattuada has, brush stroke by brush stroke, painted us a perfect picture of this Milanese auto factory boss’ existential bewilderment. And he did it with such finesse that all of our bewilderment is in there too.