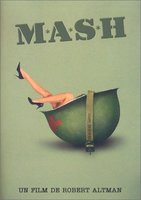

BY DAN BUSKIRK Last year I was teaching a summer film appreciation class to a bunch of middle-schoolers. You know what it\’s like if you?’re trying to pick out a film for any group, it’s impossible to come up with anything that somebody in the crowd isn’t going to roll their eyes at, but I’ve been doing this for a few years and I’ve come up with a batch of movies that really seem to work with kids. Still, I always want to try out something I haven’t shown before so last summer I decided to try out Robert Altman’s M*A*S*H with a class.

It was a disaster. About halfway through they cried out in pain and had me stop the film for minute to explain some things to them. The film, a huge mainstream comedy in 1970, was leaving them completely baffled. They could not figure out who was the main character they were supposed to be following. All the overlapping dialogue was making it impossible to hear what was going on. The bloody surgery was freaking them out, the high jinks of the Trapper John, Hawkeye and Duke were just thuggishness to them and the black humor was just darkness, scary darkness. When I told them the director Robert Altman was as important as any director whose films we watched they literally gasped in disbelief.

I should have known better. In their early teens, the kids that sign up for summer classes are not rebels so the anti-authoritarian vibe of the film was not appealing to them. What they really enjoy are heroic morality plays. Looking over the films of Robert Altman (sadly a closed set now that he has passed away at the age of eighty-one), you’d be hard-pressed to describe any of his characters as a pure-hearted hero. In the real world people may commit heroic acts but Altman understood human beings well enough to know that they are just too complicated to be summed up as pure heroes. There is hardly a Hollywood film these kids have seen that doesn’t contain a heroic lead so even this most accessible of Altman’s films left modern teenagers dumbfounded, agitated even.

teenagers dumbfounded, agitated even.

Altman’s fascination was obviously with people, that’s why his movies are usually stuffed to the gills with them. They mill about everywhere in his films; philosophizing, complaining, joking and scheming, and that’s just the peripheral characters. And in his masterpieces (no two Altman fans seem to agree on which ones are the masterpieces and which ones are the lesser works) he studies his main characters like a scientist studies a lab rat, poking and probing until all their strengths and foibles are left exposed like a frog-legged patient on the operating table. And what complete messes these characters are: Bill and Charlie, the gambling addicts in California Split, Millie and Pinky and their symbiotic emptiness in Three Woman, the cocky and dimwitted McCabe in McCabe & Mrs. Miller and Van Gogh, seething with manic fever in Vincent & Theo. Has any director gotten so much entertainment out of characters we would never want to be trapped at a party with?

But Altman put these flawed characters at the center of these films not because he wanted to expose them with scorn but because he empathized with them. Bad fate may befall them but you never had the sense that Altman enjoyed the fact that they had it coming. Maybe it was his generation. While he rode in with the young turks of Hollywood in the seventies he wasn’t one of them — Altman was forty-four when he made M*A*S*H. He was of the WWII generation and it has been said that America never loved itself and its fellow citizens more than we did after the war. While Altman’s panoramic character studies live on in the films of Paul Thomas Anderson and Paul Haggis, this new generation seems to enjoy creating their worlds so they can be the Gods who stand in judgment over them. What makes the loss of Altman seem so large is that he understood us without illusions — warts and all and then some — and still he liked us, he really liked us.