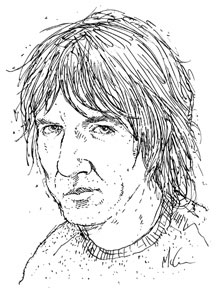

Elliott Smith, 1969-2003.

Elliott Smith, 1969-2003.

Near the end of The Royal Tenenbaums, Wes Anderson’s storybook cinematic fable of wasted potential, the character of Richie, a disgraced world-class tennis player with a dark secret, looks soulfully into the bathroom mirror. It’s impossible to say what he’s thinking — he looks scared, confused, angry, on the verge.

A tensely strummed acoustic guitar spirals in the background, accompanying a hushed, faintly ominous vocal. It’s Elliott Smith’s “Needle in the Hay.” Richie picks up a scissors and methodically, if crudely, crops his shoulder-length tresses down to the scalp. He lathers up his lumberjack beard and shaves it clean. He stares hard in the mirror, unblinking, trying to recognize the face he sees.

The music swells, whispery and unnerving. He nods slightly, pops the blade out of the razor and slashes his wrists. In the end, Richie Tenenbaum is saved.

Elliott Smith was not.

Last week he was found in his apartment in Los Angeles, dead from a self-inflicted knife wound to the chest. Sad to say, deep down nobody who knew him is really all that surprised. He lived in an orbit of despair, and he bore all the usual scars: inconsolable depression, unshakeable addictions, suicidal tendencies.

He was not a pretty man, but his music could win beauty contests. Over the course of five albums, he managed to channel a profound sadness into aching, velveteen folk-rock carols. The best of them sound like mercy itself. Eerily, his entire songbook sounds like a cry for help: harrowing, deeply wounded lyricism wrapped in gorgeous lullaby melodies.

That phrase — “a cry for help” — seems so obvious and cliched I’m embarrassed to type it. But that doesn’t diminish its tragic license for truth. What makes a man plunge a knife into his chest? What makes a man jump off a bridge? Or stick a needle in his arm?

The short answer is as obvious as it is cliched: to relieve unbearable pain. That much is undeniable, and yet it explains almost nothing. As old as life itself, suicide remains the cruelest existential riddle. A surrender to the void, a fuck-you to the world. A desperate peace wrested from ordinary horror.

I don’t pretend to know Elliott Smith, but I spent a week with him on tour and at his home back in 2000 when I was profiling him for Magnet magazine. From the outside he looked like the same badly drawn boy you saw peeking shyly out of the scores of high-profile magazine portraits that ran around the time he was nominated for an Academy Award for his song “Miss Misery” from Gus Van Sant’s Good Will Hunting. He was wearing that same brown ski cap he always wore — the one that cocooned him from the world’s harsher frequencies.

At the tail end of a months-long tour in support of his last album, Figure 8, he looked tired and thin. His long hair, unwashed for days, framed his ravaged face. I wrote that he looked like “Christ after three days on the cross.” A bit dramatic, perhaps, but no less accurate.

He played me a new song he’d just recorded. In retrospect, the irony of the title is tragic bordering on the grotesque. It was called “A Dying Man in a Living Room.”

So much of his art — bits of lyrics, album cover imagery — was a muted blare of distress. The cover of his second album, simply titled Elliott Smith, featured two people jumping off the roof of a building.

Elliot Smith was a very damaged soul. His childhood was rough, a fact underscored by his unwillingness to talk about it.

“There’s not much I could say about that time that I would like to see in print,” he said when I asked him about growing up. “I wouldn’t want to remind any of the people involved of that time.”

By his early 20s, during the flannel glory days of the early ’90s Pacific Northwest, he was playing guitar in a Portland grunge outfit called Heatmiser. After three albums he quit the band, because, he told an interviewer, when you grow up around a lot of yelling and screaming, the last thing you want to do is be in a band where everyone’s yelling and screaming.

He struck out on his own, making music that was the polar opposite of grunge: delicately acoustic, painfully introspective, full of flickering-candle reverie and blurred visions of personal disintegration. With each album, his audience grew — swelling with legions of crushed romantics, the desperately lonely and the clinically sad. Some listened to remember, some listened to forget.

By the time Gus Van Sant showed up, Smith had been crowned indie’s sun king of rainy mood-pop. And yet even as his profile rose, he was collapsing inside. He seesawed up and down between heroin and alcoholism, full-blown depression and tenuous recovery. “Shoot me up/ It’s my life,” he sang with brutal honesty.

Friends staged interventions. There were hospitalizations. At some point, he told me, aided by Paxil, he simply willed himself back into the light with this personal mantra: Things are going to work out and I am never going to stop insisting that things are going to work out.

On the last day I spent with Smith, we sat outside his bungalow, tucked away in a leafy section of Silver Lake. I asked him a lot of pretentious big-picture questions about love and death and God. At one point, I asked him if he thought suicide was courageous or cowardly.

“It’s ugly and cruel and I really need my friends to stick around, but dying people should have that right,” he said. “I was hospitalized for a while and I didn’t have that option and it made me feel even crazier.

But I prefer not to appear as some sort of disturbed person. I think a lot of people try to get a lot of mileage out of it, like, ‘I’m a tortured artist’ or something. I’m not a tortured artist, and there’s nothing really wrong with me. I just had a bad time for a while.”

Even then, I could tell he didn’t really believe that. It sounded like whistling past the graveyard.

In the two years since I spent time with Smith, I’d heard discouraging things: that he had fallen off the wagon — hard. That his manager — widely seen as one of the pillars of his sobriety — had given up on him and moved on. That his record company passed on his new album, supposedly titled From a Basement on the Hill.

His people still loved him, though. He sold out the Trocadero back in June without having released an album in three years. A few weeks ago he released a limited-edition 7-inch on the Seattle-based Suicide Squeeze label which contained two songs: “Pretty (Ugly Before)” and — again, in retrospect, this is about as subtle as writing “redrum” on the mirror in lipstick — “A Distorted Reality Is Now a Necessity to Be Free.” That’s a long way from “things are going to work out and I am never going to stop insisting that they are going to work out.”

Last week things did not work out. I don’t know if he stopped insisting that they would, or he stopped believing what he was saying. Either way, 34 years was all he could stand and he couldn’t take any more. We have to respect that. After all, he made it clear from the very beginning: Sooner or later the world will break your heart.